Thanks to Call Time listeners and Arts Journal readers for bearing with me as I took a little bit of time off last week. Unfortunately, Call Time listeners are going to have to wait for a new podcast episode, but because it will partially focus on A Chorus Line (stay tuned!), I decided to devote the Arts Journal platform this week to my favorite Chorus Line-adjacent thing, something I watch once a year at the very least, and that I consider to be the definitive encapsulation of what it means to be a working actor: the documentary Every Little Step.

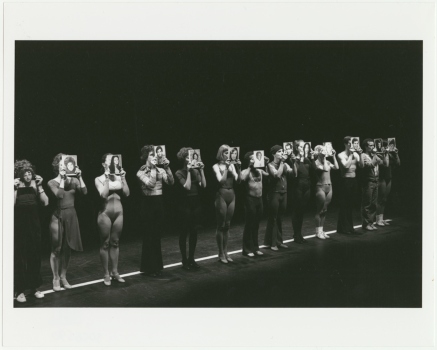

True heads may say — but Katie: why don’t you consider A Chorus Line itself the encapsulation of working/dancing on Broadway? Indeed, the 1975 musical (music by Marvin Hamlisch, lyrics by Edward Kleban, book by James Kirkwood Jr. and Nicholas Dante, originally directed, co-choreographed by, and considered the brainchild of, Michael Bennett) was one of the first “concept musicals,” and the concept was just that — a peek behind the curtain of the audition process for a Broadway musical, and the daily lives and inner workings of the heretofore faceless and nameless, “dancing chorus.”

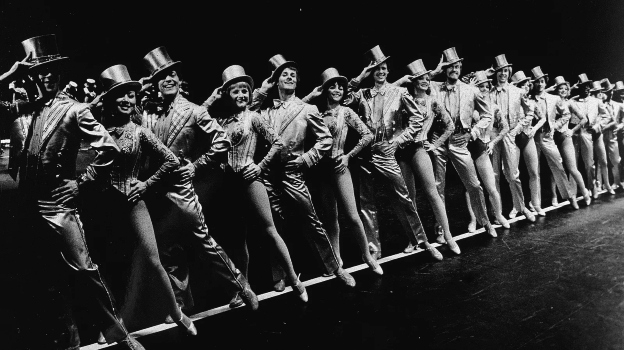

The musical won nine Tony’s, including Best Musical, and almost universal praise. Today it’s largely considered one of the greatest musicals of all time, so synonymous with the form that I’d put its opening chords — and signature, Michael Bennett choreography (ba-da-da-ba-da-da-DA-da) alongside moments like “Oh what a beautiful mornin’,” the West Side Story prologue, Tracy Turnblad’s vertical bed, “December 24th 9 PM Eastern Standard Time,” and other artifacts of musical theatre history.

But the brilliant thing about Every Little Step, the 2008 film directed by James D. Stern and Adam Del Deo, is that it adds yet another layer of meta to A Chorus Line. In a true stroke of genius, Stern and Del Deo followed the audition process for the 2006 Broadway revival. So in the doc, you watch dancers prepare for, get typed out, overanalyze, reflect on their broader lives, and ultimately book or lose a show that is itself about preparing for, getting typed out, overanalyzing, and ultimately booking or losing a show. In my opinion, the doc introduced a whole new generation to the magic that is A Chorus Line — indeed, a documentary film can ultimately reach a far broader audience than a Broadway show can, which was especially true for the revival, which ultimately closed after 759 performances. Peppered throughout the “present-day” recordings of the actors and dancers, too, A Chorus Line original cast members and choreographers reflect on the original process: what it was like that first night Michael Bennett got everyone together — supposedly with a “jug of red wine” (“terrible,” the great Donna McKechnie reflects), how Bennett opened up about his own private life in order to encourage dancers to open up about their own, and how Bennett and Joe Papp essentially invented the modern-day, Off-Broadway “workshop” structure through A Chorus Line.

But I also say that it’s the perfect encapsulation of what it means to be in “show business” because, in the same way that A Chorus Line first introduced the inner monologue of the auditioning actor to the world (“God I hope I get it…he doesn’t like the way I look, he doesn’t like the way I dance…”, the list goes on), Every Little Step introduced a whole new slew of images, vocabulary, and metaphors for the equal parts heartbreak and joy that make up a life in the theatre. One such story is that of Rachelle Rak and her audition process for the role of Sheila.

Rak is presented as a Broadway veteran in the doc — when she first auditions, the late, great casting director Jay Binder tells the rest of the “table” how she “fell sixteen feet through the trap during Look of Love, completed the rest of the show, and then said, ‘ok now I’m going to the hospital; see you in a few months.'” “She IS Sheila,” Binder goes on to explain.

Going into the final callback, therefore, it looks as if she’s the “favorite” — the role is hers to lose. But, crucially, the final callback occurs eight months after the initial audition process. After doing her final read, revival director Bob Avian takes Rak aside and tells her that “it wasn’t there today,” instructing her to try to do “what [she] did last summer.” It prompts one of the most heartbreaking “monologues” I’ve ever seen captured on film, one that plays on a loop in my head, and which I think is definitely comparable to Cassie’s “Music and the Mirror” opening salvo.

“I don’t know what I did last summer,” Rak says simply. “I had all this stuff last summer. I had broken up with my boyfriend. It was eight months ago. What did I do last summer? How am I going to repeat what I did? How do I get that back?”

It’s heartbreaking because it exposes so many hard truths about the theatre: how cruel and punishing it can be as a business, that you’re expected to recreate a performance you did eight months ago — let alone then repeat it eight shows a week, regardless of whatever is going on in your personal life or in your body. But it also exposes the fickle beast that is acting. Indeed, Avian and the rest of the creative team aren’t being vindictive or entirely unreasonable: the nature of performance is that, sometimes, that magical “it” we all talk about is there, and sometimes it’s not, and performers must consequently learn to surrender some sense of control. It reminds me of something Binder says earlier in the doc. “The way you get a job on Broadway,” he tells us, straight to camera, “is you walk in, and at that moment, you give a finished, opening night performance.”

Whatever acting teachers may say about the “journey,” and about room for a performance, and a character, to grow, that line always stuck with me, likely because of its truth. You as an actor want to feel as if you are building, and expanding, your performance over the course of the rehearsal process, but, at the end of the day, especially on Broadway, tens of millions of dollars rest on you, and your ability to perform consistently and confidently, no matter the circumstances. It may not be how you make great art, but it’s how you book a job, which is what Every Little Step, and A Chorus Line more broadly, is about. And for whatever reason, no matter how hard she tried or prepared, Rak was not giving the “opening night performance” that the creative team sought the day of final callbacks. At the end of the day, she tells the team, “Listen, it’s been eight months. I’m a big girl. Tell me if I got the job or not.” “Just tell her she didn’t get it,” a casting associate says.

Several months later, Stern and Del Deo return to Rak, and other actors who didn’t ultimately book roles in the revival. She reflects on missing the opportunity — “at the end of the day, you better like yourself, because they’re not always going to like you” — but it’s clear that, Broadway vet that she is, she’s working in another show. She pokes her head out from the stage door, still in her wig cap and makeup, with a broad smile, saying “I’ll come out, I just gotta get changed.” It’s a very classic, “show biz” moment, that always makes me think of New York, New York, Follies, Guys and Dolls, 42nd Street, or any other of these cultural artifacts that follow “hoofers” and their lives.

The doc quickly cuts from there to the actors who did book A Chorus Line as they prepare for, and reflect on, opening night. You would think that the cut is yet another heartbreaking moment, but I actually find it to be joyful, or, at the very least, bittersweet. It speaks to the way the business works: sometimes you’re up, and sometimes you’re down. For every A Chorus Line, there’s a Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, or a Fosse (for which Rak received almost universal praise). And for every “what did I do last summer?” — there’s a Jessica Lee Goldyn, who went in for the revival as a potential Val cover, and then ultimately booked the role.

And the doc does an even more brilliant cut following that. After it effectively “ends,” in a moment of triumph, as the revival company sings and performs the finale “One” on opening night, during the credits, Stern and Del Deo show footage of the huge lines of auditioning actors who showed up for the open calls. They’re lines we saw earlier in the doc, briefly, but it’s important to refocus on them if you’re the kind of person who stays through the credits of a movie. And you absolutely should watch through the credits of this movie because they seem to say: the glitz and glamor of a Broadway opening is fine — it’s great even — but the real work of a Broadway performer is the process of getting up every day, warming yourself up, getting yourself to midtown, and putting yourself “on the line.” That is the miracle of performance, and that is what A Chorus Line, and Every Little Step, is about. As another actor featured in the doc, who does not ultimately book the role of Cassie, Natascia Diaz, says, “it teaches you how to live.” Not everyone has to be an actor, going out there every day and asking potential employers to like them, and choose them, but people should be willing to put their whole selves out there — unapologetically — “and risk that it won’t work,” as Diaz says. “What I did for love”…

So whenever I get frustrated with the business — and there’s a lot to get frustrated with — it’s these moments in Every Little Step to which I return. They provide a blueprint for not only how to deal with the heartbreak and joy of the theatre, but how to deal with the vagaries of life in general: with courage, humor, hard work, and, most importantly, an unapologetic sense of self.

In conclusion, if you are any kind of theatre-inclined person, or really anybody at all, do yourself a favor, and rent Every Little Step tonight (it’s $3.99 on Amazon Prime). Come for the hard truths about the business and life, stay for Mara Davi’s virtuosic “At the Ballet,” Jason Tam’s luminous “Paul” monologue, both Andy Blankenbuehler and Amy Spanger getting rejected (happens to the best of us!), evidence of a time before every musical theatre dancer only dressed in Lululemon athleisure, Nikki Snelson’s abs, a pre-So You Think You Can Dance Tyce Diorio, early 2000s shots of Ripley Grier, and tons of inside baseball moments like “oh yes I saw you at Papermill!,” “we did All Shook Up together,” and “you have to keep playing with your hair or else it looks wiggy.” While critics largely thought that the Chorus Line revival felt “recycled” or “pedestrian,” Every Little Step makes the peek behind the curtain feel new, raw, and real again. I believe Bennett would be proud.

A magnificent telling of the life of a Broadway dancer, or actor! What a sad, yet joyful calling—-evidently one which very few who aspire to the job are willing to give up, in spite of the frustrations and rejections! You, and the documentary, explore this situation beautifully, with wisdom and heart!!! Congratulations for letting us peek behind the curtain with you and capturing the hearts and souls of performers!!!