Consistent readers and listeners of Call Time may be overloaded with information about dancers and the dance world right now, but, after my incredible conversation with Sophie Blue last week, I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to interview one of my actual Princeton classmates, Alexander Quetell, with whom I overlapped for three of my four years and with whom I worked on many memorable theatre/dance projects. After three years and change of “freelance” dancing in the Seattle, Los Angeles, Detroit, and Montreal areas, as we discuss on the podcast, Alexander now dances professionally for a contemporary/modern/ballet/you-name-it company in Munich, Staatstheater am Gärtnerplatz. German speakers, or even clever English readers who are good with the cognates, may recognize that Gartnerplatz isn’t any old company in the way we in the United States think about dance, theatre, or opera: Staatstheater am Gartnerplatz literally translates to “the state theater at Gärtnerplatz;” as Alexander gleefully tells it, “[he’s] a state employee of Bavaria!”

To that end, Alexander and I delve into the details of what it means to move from the United States to Europe as an artist. To some extent, the choice was creative/aesthetic, Alexander says: “I was looking to the choreographers that are here, the people I was interested in working with, the work I was interested in doing.” This makes sense: as a dancer with training in multiple genres (he was a self-professed “competition kid” after all), who choreographs nearly as much as he dances, Alexander is now most interested in the “contemporary” dance space, a tradition which, though purposefully “vague,” he believes combines “different movement languages” that rely heavily on “improvisation,” “different experiences and textures of the body,” and the way “the body can feel an emotion.”

In our interview Alexander cites some of his greatest inspirations and influences as Gaga — the movement language and pedagogy popularized by Israeli choreographer Ohad Naharin, the work of Merce Cunningham, known as the “Cunningham Technique,” and connections between dance and theatricality. Alexander and I discuss different schools of thought in the acting world, which place emotions either first in the head or first in the body.

Given these creative interests and influences, it makes sense that Alexander would be interested in working in Europe. “Commercial dance has a larger market in North America,” Canadian dancer Paxton Ricketts said in a 2016 Dance Magazine article, “and concert dance has a larger audience in Europe.” “I have a long list of choreographers that I have been wanting to dance,” Dustin True, a dancer with the Dutch Ballet, said in a 2020 article for The Observer, “and most of them have made their careers in Europe.”

Another major reason for Alexander’s move — which is indelibly connected to the rich talent and creativity centered in Europe, especially when it comes to modern/contemporary, “concert” dance — was financial. As we note at the beginning of this article, Alexander is a state employee of Bavaria: and with that comes 44 weeks of consistent work, healthcare, and “two” pensions. “I don’t have to work three different jobs like I had to in the US,” Alexander says of his career in Germany, “I can do my work, and also just live.”

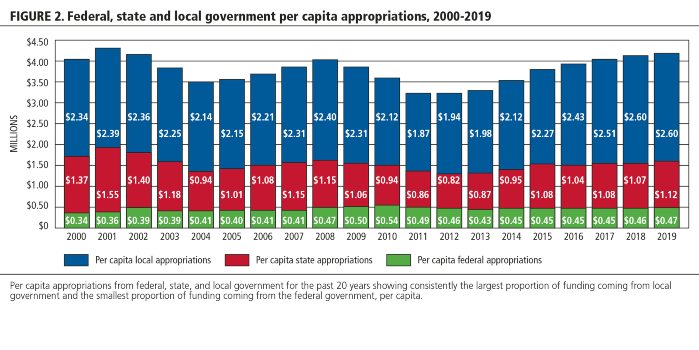

This happy financial situation for a dancer like Alexander is obviously connected to the way that dance and the arts more broadly are funded in Europe. As in most other countries on the Continent, the German government subsidizes dance, as well as opera, theatre, and classical music — to the extent that almost every city in Germany hosts resident ballet, opera, and/or theatre companies, as well as orchestras. “It’s within the right of Germans to have access to and support for culture and the arts,” Zarina Stahnke, a dancer in Dresden, explained in the 2020 Observer article. “Having access to the performing arts has been so skewed in the U.S. as to seem like such a privilege, it almost sounds absurd to think of culture in the context of a human right.”

To an artist in the United States, especially one primarily working in musical theatre, this sounds like the Promised Land. Even the thought of not having to explain to my accountant why I have so many different W2s in a year sounds like a dream. But of course, I’m not advocating for the United States to switch over to the Continental European system with a snap of my fingers: there are drawbacks to any financial system, and, as Alexander explains in our interview, working for a state theater means that, in addition to performing the incredibly exciting choreography for which he moved to Europe, his company must also spend a great deal of time performing in operas, operettas, and musicals — like a run of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang he had just closed when we chatted. While Chitty Chitty Bang Bang — even in German — is more my bread and butter than Gaga or Cunningham (I suspect I’d look like a chicken running with its head cut off), these projects are understandably not what lights Alexander’s fire, and are just part of the job when you work for a state institution. Similarly, I believe that art is always — and should necessarily be– political, and I wonder what a “state run” theater under the Trump administration, for example, might have looked like (let’s just say I don’t think it would have been doing Angels in America).

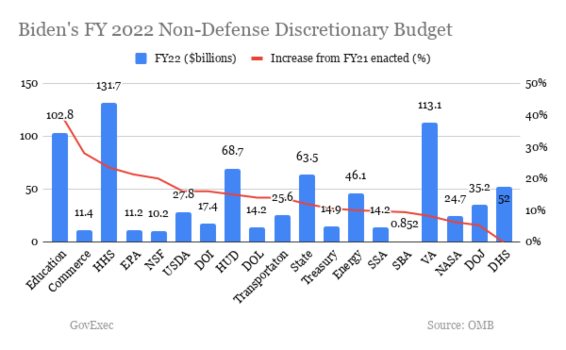

Nevertheless, based on what I’ve witnessed in my professional career — especially during and after the pandemic — as well as my academic work, it’s clear to me that there’s some sort of hybrid situation that could be achieved; a government-supported arts system, without the politics; and the NEA simply isn’t cutting it. Indeed, only 6.7% of arts funding today derives from government sources. As a 2017 CATO report stipulated: the arts sector in the United States would largely survive — and generally DOES survive — without NEA funding, a drop in the bucket compared to what the government spends on other social services.

While the CATO Institute was using these facts to argue that the NEA should be eliminated altogether, I would wager that they support the concept that the body should be reconceptualized and remodeled. It doesn’t have to look like the state theater system in Germany or France, but it can look like the American version (and that’s not hard to imagine: we need only look to FDR, the WPA, the Federal Theatre Project, and Eva LeGallienne’s Civic Repertory Theatre for inspiration).

But for now, because we don’t have that, Alexander makes his artistic and literal home in Munich, where he dances six days a week, with time for some choreography of his own on the side (he started Waltz I in 2021, Waltz II in 2022, and will begin Waltz III in the coming year). While Alexander feels the pull of his family back in the states, he says he could see himself living in Europe full-time. “It’s about the quality of life,” he says. For a dancer interested in cutting edge movement languages, collaboration, improvisation, and “learning as much as [he] can” — I get it.

If you’re dying for me to get off my soapbox about arts funding, you can listen to our whole interview, in which we spend only a few minutes on the economics of art, and many more minutes on things like the influence of So You Think You Can Dance, incredible Princeton funding and financial aid packages, ageism and ableism in dance, moving coins on a table (the tried and true method of all directing and choreographing), and why Germans are obsessed with tapas.

Leave a Reply