I was so happy to be able to interview actor Peterson Townsend, featured in TV shows like Law and Order: SVU, Gossip Girl, and Elementary, and on the stages of theaters like Arden Theatre Company, Barrington Stage, the Metropolitan Opera, St. Louis Rep, and the Mint Theatre Company, on my episode this week. You may be wondering: Katie, will you ever stop interviewing people associated with the Mint’s production of Chains? And my answer would be “maybe someday, but probably not.” It’s a testament to how many amazingly talented, different kinds of people and artists that production brought together that nearly every week I say to myself — I bet XYZ would be an incredible guest. You can listen to previous episodes with Jonathan Bank, Claire Saunders, Laakan McHardy, or Rob Signom here.

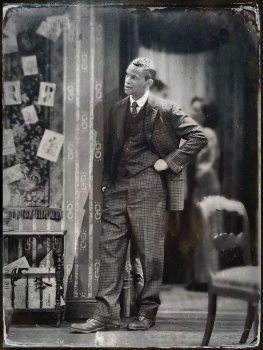

I knew Peterson would be a good addition to the group first because he is extremely talented and gave a compelling performance as Mr. Tennant, the “tenant” (ah, see what Elizabeth Baker did there?) who sets the whole Chains plot in motion when he tells his landlords that he’s off to the Colonies. Second I knew he’d be a great guest because, knowing him personally and doing some research on his resumé, his career displays remarkable variety.

One year he’s doing period pieces like Chains or Christmas at Pemberley, and another, or perhaps in the same year, he’s doing American classics like A Raisin in the Sun, Greek tragedy like Antigone, or contemporary plays like America v. 2.1: The Sad Demise and Eventual Extinction of the American Negro. We discussed how and why Peterson is able to do all this — turns out it’s a mix of luck, cultivating a good relationship with your agent (Peterson has been with his for twenty years!), and, of course, good training. Based on our conversation, however, I’d also venture to say that part of it is Peterson’s impressive goal-oriented attitude. Indeed, he explained that his father was in the military, the rest of his immediate and extended family are teachers, and therefore the conversation about choosing a life in the theatre, one with which many of my readers and listeners may be familiar, required determination, faith, and a strong sense of self, even at an early age. Peterson also describes how he was a runner — a sprinter, to be exact, and how that background shapes his approach to theatre and performance even today. If he was going to do it, he says, he was going to go “all in,” desiring a theatre “bootcamp” kind of experience, with intense, all-consuming training.

He recalls a particular race toward the end of his high school experience: he was running the 400 — just one lap around the track, his favorite race. But he describes how this particular day he felt all the pressure of that favoritism: if he liked it less, or if he was less good at it, Peterson says, he wouldn’t have been scared at all; it was the expectation of winning, or of achievement, that lay heavy on his head. Not only that, but he felt the culmination of all those years of work, toil, and teamwork surrounding him; it seemed as if everything was dependent on this one, super short race. As he got into position, Peterson describes, he realized that he couldn’t feel his hands “from the elbows down.” Panic set in — as it would for anyone: what if he failed his teammates, his classmates, his family, himself? What if all this hard work and the hours in the track were for nothing? What if it felt as if the entire future of your life was dependent on the next 10 seconds?

It’s a feeling I know well. I think many people assume that performers — or even professional athletes, anyone whose work depends on live events — never get nerves or anxiety. Peterson’s description of not being able to feel his hands was a familiar one: I had that exact feeling of numbness, a sort of out-of-body fear, for many professional auditions — especially those that I considered “high stakes.” It’s even a feeling I can remember when I’ve taken important standardized tests, the SATs, or the GREs more recently. The cognitive dissonance for me, as I describe on the podcast, has always been this sense that the rest of my life, and the opinions of my friends and family, rests on this one, in some cases very short, moment. Peterson describes this particular race because it turned out to be his breakthrough. He says that “all of a sudden, this voice in my head told me — you don’t need your hands to run. And then the gun went off, and I just ran.” He realized that, in moments like this, all you can do is rely on your training and practice to help you live in the moment.

It’s a lesson from which I think many actors, artists, athletes, or really anyone can learn. Indeed, Peterson said he had that feeling before going out onstage every night at Chains. Each time, he had to get out there, and rely on his training and his self-knowledge to carry him through. And in a two-month run like Chains was, there are bound to be times when you exit stage left and think, “not my best.” And to me, that’s the key. In times of great stress and anxiety, when it’s all-important that you live in the moment, I always had to tell myself that I would be the same person twenty minutes later, whether I made a fool of myself or whether I got the role. Whether you win or lose the race, you have to just run.

It’s a theme I wish more actors discussed in depth, although I understand why it’s difficult to write or talk about: every performer struggles with this feeling in different ways, and therefore every performer has had to come up with their own unique alchemy to combat it and center them in the moment. In my opinion, it’s why so many actors meditate, practice yoga, or have very specific, almost superstitious pre-show rituals. I asked Peterson on the podcast about that too: it turns out that’s yet another connection with running. Before every show, as I saw with Chains, Peterson goes onstage to warm up — but he’s not doing Laban exercises or Alexander breathwork. He’s doing running exercises: stretches and warm-ups he learned and honed from years on the track team.

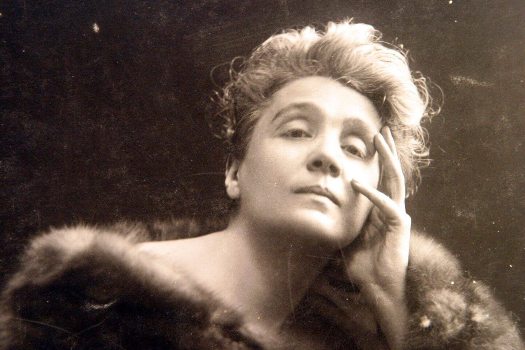

Clearly, that’s worked for Peterson. It’s how he’s been able to sustain a career in the theatre for nearly twenty years while constantly expanding and deepening his skills, techniques, and portfolio. Many of my guests, even if they attended prestigious conservatories like Juilliard or Yale School of Drama, have described how they learn the various acting techniques but then, in practice, just take bits and pieces of what works. If that’s Meisner — then that’s fantastic. But if it’s rolling your shoulders in a very particular way or doing track and field pre-race stretches, that’s great too. It’s why I’ve also always felt that there’s something mystical about the theatre: performance depends on an unknowable connection between mind and body that can only be vaguely guessed at or manipulated through obscure techniques, mantras, or even prayers. Why else is the theatre filled with superstitions (“break a leg” “thank you five” “the Scottish play”), ghost stories, and even mystics themselves, like the late, great Eleonora Duse?

Beyond these esoteric musings, Peterson and I also discuss the nuts and bolts of moving to New York in the early stages of your career, the importance of fellowship and community in the theatre world, the lifelong, and genre-defying, value of storytelling, the Metropolitan Opera, growing up in Germany, summer stock, and the circumstances under which you’d have to wear Red Sox gear while doing theatre (hint: anytime you’re performing in Massachusetts). Listen here.

A GREAT article,!! So thoughtful and insightful regarding acting and performance in any field!!! This is one of your best!!!