It’s a tale as old as time. The drama department of a college or high school is filled with talented young women, and people of other under-represented genders, who are nearly bursting to get up onto the stage and prove themselves. Yet time and again, it’s the same old story: the drama department does Hamlet, Death of a Salesman, The Iceman Cometh, or even something like The Producers or How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying. While one of the reasons I fell in love with musical theatre in particular is because of the fantastic roles the canon has produced for women — and much has been written about this, the same could be said of the NY, professional theatre scene, and the shows produced on and off Broadway in any given season.

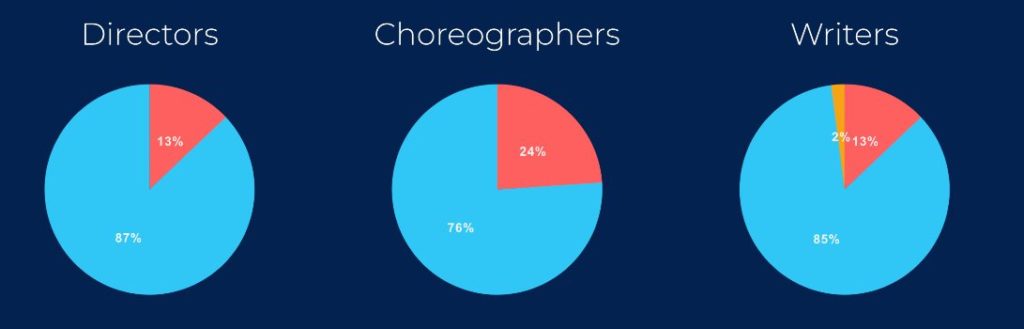

While 2019 was a banner, pre-pandemic year for NY theatre, only 32% of that year’s title characters were women (0.27% were non-binary and 7.1% identified as “unspecified gender“). In the UK, male-identifying actors outweigh female-identifying actors 2:1, and The National Theatre, in many ways the standard-bearer for both theatrical tradition and innovation in the UK, has the lowest representation of female actors in the country, at 34%. The situation is even worse behind the curtain. In that same, 2019 “banner year” for Broadway, only 13% of directors identified as women, 13% of playwrights, and 24% of choreographers. Women represented only 30% of set designers, 22% of lighting designers, 13% of sound designers, and 6% of stage carpenters (we tend to do “better” in the still traditionally female-coded hair and makeup departments).

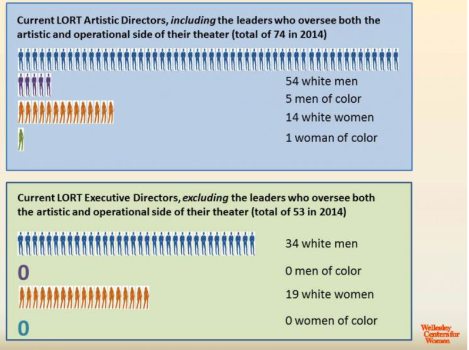

Women and other under-represented genders by and large don’t tend to lead or produce successful productions either: in a 2015 study conducted by The Wellesley Center, it was found that only 14 women acted as Artistic Directors of LORT theaters (League of Resident Theaters, the largest and most prestigious network of theaters beyond the Broadway League) (out of 79), and only 19 acted as Executive Directors. The situation is even worse for women of color, who, at the time of the study, only represented a single Artistic Director in the entire network of LORT Theaters — and no Executive Directors.

And while the situation has improved since the much needed calls for increased equity and representation of all kinds after the murder of George Floyd, studies suggest that even in today’s post-2020 theatrical climate there’s an inverse relationship between the involvement of women and other under-represented genders in high-profile shows or theaters and their budgets. Essentially, wherever you go and wherever you make theatre, you can rest assured that the theatre will live by this rule: more women, fewer resources; fewer women — you got the golden ticket.

This was why I wanted to interview Julia Greer as soon as I met her. As just a college student at Kenyon College, a small, liberal arts school in rural Ohio, Julia, as well as her co-founder and co-Artistic Director, Emma Miller, recognized this fatal flaw in the theatrical system. While it provided excellent training, Julia realized that the Kenyon theatre department didn’t consistently produce vehicles for young female talent, when the department was nearly bursting with it. After what she describes as a “magical” time working for female trailblazer Paula Vogel, developing Indecent at La Jolla Playhouse and Yale Rep, Julia and Emma discovered that the problem wasn’t unique to Kenyon or even to educational facilities: the professional theatre scene, in NY and beyond, was not producing works by, for, and about women. And even when they did — as NY Times theatre critics Laura Collins-Hughes and Alexis Soloski noted in a 2016 article — rarely did the pieces cover the full spectrum of what womanhood can be and mean. In our conversation, Julia noted over and over again that she’s drawn to works about women that are “complicated,” that “challenge stereotypes,” and “expand our perceptions of what it means to be a woman.”

Beyond my interest in older, Golden Age musicals and plays, my major academic and literary focus, as well as my more casual, cultural appetite, has always centered around complicated women. Often these two passions merge in interesting ways: my English thesis at Princeton focused on the relationships between women in Jane Austen novels, and the unique blend of jealousy, competition, admiration, envy, love, and hate that often comes with female friendship, and my Theatre thesis melded the musicals Annie Get Your Gun and Gypsy into a single evening of theatre exploring the relationships women have with their families/lovers vs. their careers and ambitions. As Collins-Hughes and Soloski note in their article, “female stories” don’t always have to be about babies, motherhood, or heterosexual love. “Men get to struggle with politics and power and art and conflicts deep within the self [onstage],” Soloski argued. How great would it be to see how women, and women writers, directors, choreographers, designers, and technical staff, contend with these issues?

And that’s essentially the mission of the theatre company Julia and Emma founded, entitled The Hearth. Since 2016, the Hearth has attempted to fill in the gaps in the NY and regional theatre scenes by producing work by, for, and about women and other under-represented genders.

In her capacity as co-Artistic Director and co-founder, Julia has overseen the production of numerous new plays like Baby Cakes, She Buried the Pistol, Nurse Sluts (which Julia also co-wrote), and, most recently, Happy Life. In her capacity as an actor, Julia has performed with the Hearth and beyond, in plays like Ransom, Extremely Grey Line, The Commons, and in films like Noah Baumbach’s Marriage Story and Zach Braff’s upcoming A Good Person. In our discussion, Julia even brings us along for the journey of Athena: a play that she nurtured and produced from its earliest stages, starred in Off-Broadway, and then got to see licensed and produced across the country, particularly in school environments, giving young women the opportunity to confront issues of womanhood, identity, growing up, friendship, and competition through their artistic practice. In my opinion, Julia is the kind of person we need at the forefront of the gender parity discussion because not only is she interested in employing women at every level of the production process, but she’s also interested in the work itself, and what it means to represent yourself as a woman, or tell a “woman’s story,” onstage. As our perceptions of gender expand and change, so too can these stories and discussions.

Listen to my full interview with Julia, where we also cover the day-to-day runnings of small, NY theatre companies, fundraising and grant writing, scrappiness vs. “selling out,” messaging random girls from high school to “fill seats,” whether the musical Annie is actually a feminist totem, and having time to watch TV.

Leave a Reply