On the day of the Comey hearing, we sat in a bar in Paris watching CNN. Lordy, that was a lot of talking.

As if to balance that experience, we went to a piano recital in Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, the first art deco building in the city. It’s a fine and intimate space for about 1900 people. That night it was full—the concert appeared to be sold-out. The audience was pretty white (as is the center of Paris), but not so old as we’ve come to expect at a classical music event in the US.

We had seats in the second balcony, as we like for the acoustics, with a perfect view of the pianist’s hands. Above us were small window openings between our balcony and the dome. As the concert started, people leaned out of the openings, some sat on the ledges—apparently, that’s the only way to see from the gallery seating. This leant an informal feel to the space and the concert.

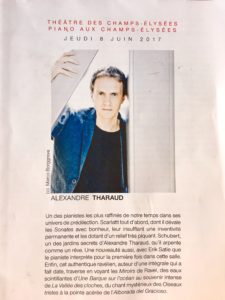

The performer was Alexandre Tharaud. I’d never heard of him, but my mother (a symphony musician for much of her career and now the artistic director of a chamber music series) did the research and she was excited to hear him. He’s apparently a little more famous than the usual pianist because of his work in the film, Amour.

The concert was ELECTRIC.

There was no talking.

None from the stage before he played.

No announcements about upcoming concerts. Nobody thanked funders. Nobody talked about the music we would hear.

Just a man and his piano.

He played Schubert Impromptus after the break and the audience could not be contained. Clapping between parts was exuberant and no one looked askance—we didn’t hear any shhhhhhing.

At the end of the concert, the audience did this thing they do there: They clapped and clapped until the clapping was synchronized*, which signals extreme liking and a desire to hear an encore. In other words, hundreds of strangers worked together to ask Tharaud to play more. No one stood.

Tharaud came back out. FOUR TIMES. Four encores. With the audience doing that unison clapping each time.

On his fourth visit to the encore stage, he played Gershwin’s The Man I Love, not exactly typical classical fare.

There were many possibilities for what made this concert experience magical. Of course, it was an incredible antidote to USA politics and the many words of the Comey hearing.

But what stood out for me was this: not a single word was spoken from the stage the entire evening. Music first.

+++

This summer we’ve seen two must-read columns from art critics about declining audiences for the arts in the USA.

One, the first I read, by Chris Jones of the Chicago Tribune, is provocatively titled: Like it or not, we are in the midst of a second arts revolution. He quotes Steven Tepper, now Dean at Arizona State University’s Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts, who describes this moment in time for the arts as one of “the exuberant expression of self.”

One, the first I read, by Chris Jones of the Chicago Tribune, is provocatively titled: Like it or not, we are in the midst of a second arts revolution. He quotes Steven Tepper, now Dean at Arizona State University’s Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts, who describes this moment in time for the arts as one of “the exuberant expression of self.”

Then Jones notes that arts supporters may have already noticed this. “And it’s not good for an arts organization that expects its audience to sit down and be quiet.”

In other words, pretty terrible for classical music, traditional theater and dance, and many museums. Jones notes that these days we can all make our own shows, music and video we stream or create. Plus, we can all be critics—everyone has a megaphone. (Like this blog, heh.)

He writes, “Is all this good for America? It’s not really a relevant question; it’s happening anyway.” (Think about that last sentence before you send me your complaint about the loss of tradition, please.)

His prescription? “…the truth is that everyone working in culture, and hoping to survive, has to provide much more opportunity for engagement than now is the case. Festivals work because they foreground a social experience over the actual performance; the best of them understand you’re not really coming for the music.”

I’ve thought a lot about the recital in Paris and know that the experience included only the slightest of shifts that made us feel more engaged. People hanging out of ceiling openings, clapping between movements, focus on the music (not the presenting organization), surprise encores preceded by collaborative clapping—these are relatively small things. But cumulatively, and because the music was glorious, the performer spectacular, the concert is a highlight of my year.

What makes those small moments of engagement possible in a classical music venue? One answer is found in the second column of the summer. Anne Midgette of the Washington Post wrote that, sadly, “The real motor of the performing arts isn’t vision. It’s the board, stupid.”

What makes those small moments of engagement possible in a classical music venue? One answer is found in the second column of the summer. Anne Midgette of the Washington Post wrote that, sadly, “The real motor of the performing arts isn’t vision. It’s the board, stupid.”

She shares that boards often (not always, of course) get in the way of creativity, telling the saddest tale about a new artistic leader who, after a fundraising visit to the notoriously vibrant workplaces of Silicon Valley, finds himself wishing he too “worked for a creative company.”

Why does this happen? “… often enough, boards are invoked…as figures of fear—particularly when it comes to trying out new things. The boards of large classical music institutions are often committed to maintaining a traditional status quo, especially when it comes to opera, where the incursion of contemporary, probing productions is seen as a plague by some conservative audiences.”

Midgette also concludes that change is necessary. “Maybe someone needs to bring vision to the fallacy, almost universally accepted, that the only way to sustain the arts we love is to shore up a system of oversized institutions that no longer seem to work well in today’s culture.”

These are scary words for the leaders of big, old presenters of classical art. It won’t work to deny them though.

*Synchronized clapping—it’s fun.

As a callow country boy back in 1960, I went off to an American prep school (Exeter). One of the many astonishing customs I discovered there was synchronized clapping. At the time, I thought OK, so this must be what sophisticated people do but I’ve never run into it again here in the US. I have no idea if it still happens at Exeter.

Thanks Greg! I had no idea.

I’m an American classical musician who has lived in Europe for 38 years. Performers need to know the differing customs of applause to understand the reactions to their music. American audiences aren’t as eager to show their enthusiasm as in Europe, but it does not mean they are less appreciative.

In Germany and France, long, enthusiastic applause isn’t only an appreciation of the performer, but just as much, a celebration of culture itself. It’s a public demonstration of people wanting to show that their society stands for higher ideals. Sometimes there are individuals who make a show of their applause to demonstrate their “cultivation,” but the collective applause is generally not like that not like that. Through their extensive public funding systems for the arts, they feel invested in their culture. It belongs to them. Through their applause, they celebrate their own identity.

Europeans are also much more inclined to celebrate cultural heroes and even worship them as “artist-prophets.” This ethos was closely tied to the rise of cultural nationalism in the 19th century. Support for the arts became a kind of patriotic duty. Cultural nationalism and the rise of artist-prophets created a lively arts world, but by the 20th century it had created perspectives that became catastrophic. See:

http://www.osborne-conant.org/prophets.htm

Thank you for your interesting article. The low-keyed language of the cultured American abroad is also a cultural study in itself.