This Week’s Insights: Classical music by any other (marketing) name… Dance companies finding new customers in dance-related ways… The Met Museum’s audience admissions dilemma… What should we really know about our audiences?

- Classical Music’s Identity Problem: Even the composers these days don’t call it classical music – they prefer “genre-less.” Is it a marketing issue? Not entirely. “Classical” describes a specific period in music, and what we’ve been calling classical spans many periods, so it’s not accurate. But there’s also the marketing problem. “Crossover” is an invented category that blends pop with classical. But there’s a problem with that too. “As classical music searches for a wider audience, classical crossover poses an increasing conundrum — not least because it’s attracting exactly the audience that ‘straight’ classical claims to be seeking. The mass audience is generally put off by classical music, which seems, to many outsiders, to present a facade of unwelcoming elitism. The crossover genre, however, offers the same kinds of mellow tonal sounds and rich buttery voices — music to relax to, if you will — without classical music’s perceived strictures or judgments.”

- Expanding The Dance Business Model (aka finding new clients?): In 2010, the Future of Music coalition reported that musicians had 42 sources of income. Many musicians make more from merch sales and their ancillary music-related than they do from actually playing music. Rather than distraction, though, expanding sources fed fan interest. So could it work for dance? “L.A. Dance Project recently launched the subscription-based ladanceworkout.com, offering streaming workout videos led by company members. Groups of all sizes and even some individual dancers have launched merchandise lines bearing their logos. And, of course, there’s the perpetually innovative Pilobolus, which has been in the creative-revenue game for years, with books, advertisements, corporate appearances and more.”

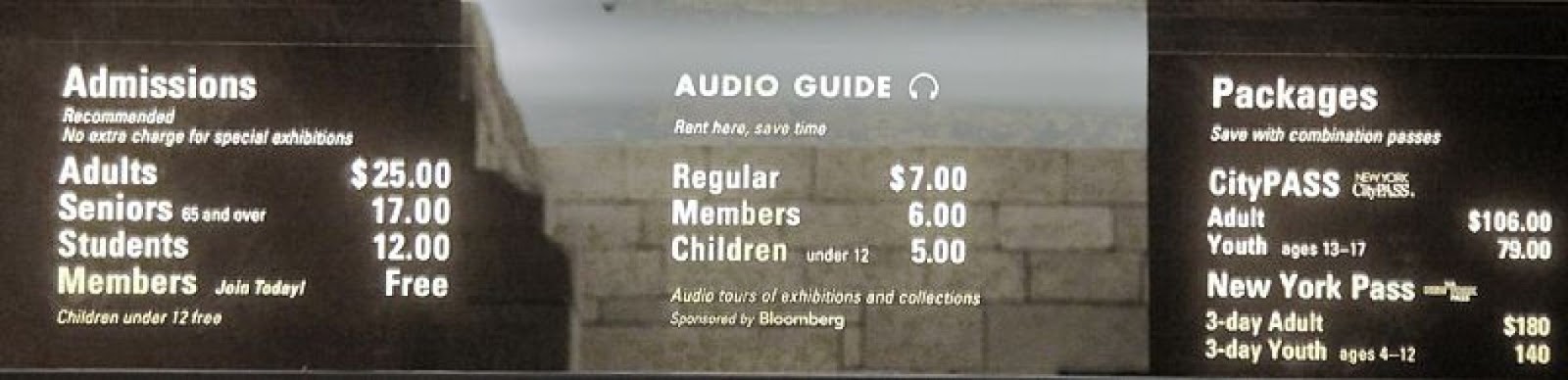

- What The Met Museum’s New Admissions Policy Says About How It Sees Its Audience: For years the Met has had a pay-what-you-wish entry policy, with a “suggested” donation prominently posted. This week the Met made the fee mandatory for non-residents of NYC. The move should only raise about $6-10 million a year on a $300+ million budget. More revealing was the revelation that the percentage of visitors paying the full suggested fee had slipped from 63 percent to 17 percent over the past 13 years. This while the Met saw a dramatic increase in visits from 4.7 million to 7 million per year. So many ways one could see correlations. Perhaps visitors come more often because they don’t pay the full amount. Or perhaps a growing number of visitors don’t feel the experience is worth $25. The Met’s new policy only applies to out-of-town visitors so perhaps the museum’s calculation is that they’ll come only occasionally and hence be willing to pay full price. Still, the new policy creates different classes of visitors (which many businesses do). And if half of the out-of-towners who might have come at a lower price now take a pass, the Met’s hoped-for revenue gain could be negated. And so? The museum is overcrowded. Fewer visitors could improve the experience for those who still come. Some cities use tolls to reduce traffic on their freeways and improve flow as they collect revenue. And there, perhaps is the real issue: a pay-as-you-wish policy makes using the museum accessible for all. A $25 toll means some won’t be able to afford it. More important perhaps will be the greater number who will weigh whether the visit is worth it.

- Let The Inmates Control The Asylum? The new director at Shakespeare’s Globe in London says she wants to “dismantle theatre hierarchies.” To that end, she wants to give more power to the actors and the audience. Who will it work? “None of the actors turning up for rehearsals [for Hamlet and As You Like It] will know which role they are taking, with the whole ensemble choosing who plays whom. In a similar vein, when the plays The Merchant of Venice, The Taming of the Shrew and Twelfth Night go on tour, some audiences will be able to choose which one they want to see that night.” Will this make better theatre? Will it make better experiences for actors and audience? Or is this power of choice that no one asked for and people don’t want?

- What Do We Know About Our Audiences? Three new studies take on the question: “Does it matter if we know why people choose theatre over other offerings, as long we can sell them tickets? Consider that if we better understood why theatre has a unique intrinsic attraction to human beings, we could change the way society views—and values—the art form altogether. Oddly enough, even as the world has become more globalized, interconnected, and plugged in, the practice of behavioral research for marketing purposes and the promotion of the arts largely haven’t found alignment. That situation appears to be changing, as researchers are now starting to examine the effects of audiences on the arts, and the effects of the arts on audiences. That’s great news for American theatre.”

Regarding article 1, do we perhaps need a term for a genre called “cross down”? If we want to reach the masses with classical music, should we not candidly admit that we will need to meet lower, more common standards of education and cultural sophistication? Let us embrace crossing down!

Ach, but there’s a problem since that sounds a bit snobbish. Perhaps we could take a cue from high schools and how they categorize their sports teams based on the size of the school. Everyone gets to be in an A category, such as AAA, AAAA, AAAAA.

Well, no…that’s too awkward. I’ll guess we’ll have to stick with the euphemism of cross over and just ignore which dimension we are moving through. Even better, let’s pretend that up/down dimension doesn’t even exist and that we live in a flat two dimensional world where everything is on the same level.