Rich and Lonely

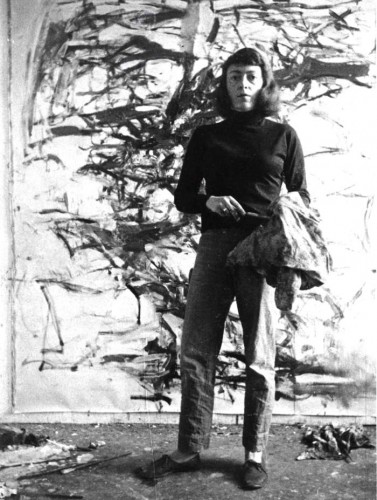

Joan Mitchell (1925-92) committed her First Sin by being a woman artist with more talent than many of the men in her generation. Nevertheless, being in the second generation of Abstract Expressionists was her Second Sin. No one ever wants to be the second generation of anything. Is that why we had Neo-Geo and the Pictures Generation instead of second-generation Pop Art?

Her Third Sin was that she had been born to a wealthy Chicago family. Artists, male or female, way back then, had to be starving artists living in cold-water flats. And then there was the Chicago part of that, in spite of her graduating from that city’s Art Institute. Can you name one famous Chicago artist before Leon Golub? And Golub, after trying out Paris, had to move to New York.

Her Fourth Sin was more complicated. After establishing herself on 10th Street, she moved directly from the Big Apple to France. Critic Clement Greenberg – the power broker of Abstract Expressionism – told her not to. But love for a French Canadian racing-car driver (who was also a celebrated painter) made her move. That’s a woman for you, said many at the time, shaking their heads — not necessarily about moving to Paris, but about being smitten with Jean-Paul Riopelle.

If a man at the beginning of his career had disobeyed Uncle Clem and moved to France to be with the love of his life, that would have been exciting, thrilling, romantic. When a woman follows her heart, she is just a woman. When a man follows his heart – or his whatever – he is a hero.

So Mitchell’s Fourth Sin was a compound sin. She disobeyed Greenberg; she followed her heart; and, probably worst of all, she moved to France when America had established artistic hegemony thanks to Greenberg, Harold Rosenberg, and the U.S. State Department.

But, let’s face it, American painting was indeed better than European painting after the war, wasn’t it? Soulanges, Dubuffet, Hartung, Fautrier, Wols had been outclassed by Pollock and de Kooning, with Newman and Rothko rising fast. New York refused to recognize even the great Yves Klein. Too wacky. The New York School (Rosenberg’s phrase) had buried the School of Paris. Good riddance.

And it got worse. Mitchell stayed and moved outside Paris, quite near where Monet had captured some of his most famous works. Her gardener and her cook actually lived in Monet’s cottage.

If you squint, Mitchell’s ultra-painterly, ultra-tactile paintings seem to have something to do with nature. If not depictions, then certainly in a wild spirit that is always just right and almost always breathtaking. However, when she moved from Paris to Vétheuil (where, with an inheritance, she purchased a rambling estate), it was not to be closer to nature, but to please Riopelle.

Her Fifth Sin was that she didn’t have a wife to promote her and steady the helm. Wild woman Alice Neel once told me, when I was posing naked for her, that she would have been famous much sooner if like Jackson Pollock she had had Lee Krasner for a wife, or like de Kooning she had had an Elaine. Mitchell had been married to Barney Rosset, a high-school friend and eventually the brave Grove Press publisher of Jean Genet, Henry Miller, and William Burroughs. But later, Mitchell took up with the painter Mike Goldberg. And then, in 1955, Riopelle. Her stormy relationship with Riopelle lasted until 1979 — a good quarter century of brawling.

Mitchell by the Book

I read Patricia Albers’ Joan Mitchell, Lady Painter: A Life. Mitchell sometimes referred to herself ironically as “lady painter.” If you want details of Mitchell’s love life, gay best friends, and her illnesses, this is the book for you.

Mitchell, in or out of her cups, had a bad case of what we used to call the “frankies,” an affliction related to alcohol. She was frank to the point of rudeness. But she wasn’t quite the woman often depicted by Bette Davis or Joan Crawford. Her life would not make a good movie — which is her Sixth Sin. She had many house guests, but was apparently always lonely — the plight of too many poor little rich girls (and boys) cursed with not having to work for a living.

She was famously rude to Whitney curator Marcia Tucker, who was trying to arrange a show while Mitchell and Riopelle were throwing things at each other, including a dish of oeufs au plat. Tucker stood up to her: “I have had enough. I can’t work this way, and I won’t. If you want this show to happen, then you’re going to have to start behaving, stop insulting me and get to work. If not, then I am finished here. I don’t need to do this show, and I’m just about to the point here I don’t want to.”

For once, Mitchell obeyed.

Mitchell led two lives. Her personal life was a train wreck. The life does not match the brilliant paintings. Sometimes the most messy, messed-up, discombobulated souls are awarded, in compensation, the gift of the gods: in Mitchell’s case, the genius of painting. The further away you get from Mitchell the drunk, the closer you can get to the paintings.

Oddly enough, she was farsighted and had to step way back to see her own work. So do we. Time has been kind to her art. I rank her second only to Pollock and de Kooning. In fact, she too melded nature and facture.

I Have Never Seen a Poem as Lovely as a Tree

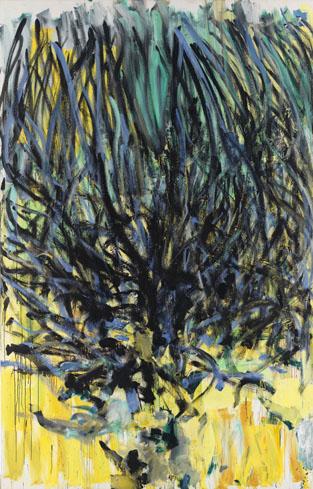

The current sampling at Cheim & Read called “Trees” (to August 29) underlines Mitchell’s links to the visible. Her trees, however, are even less like trees than those Mondrian painted as he battled with himself to be free of Cubism, taking one step at a time toward what still passes for total abstraction or non-objective art. We are more canny; we see square Dutch fields and the mid-Manhattan grid.

After Mitchell moved to France, she adapted two- and sometimes three-panel formats, because her studio spaces, first in Paris, and then even in Vétheuil, were always too small for her vision and for the newly required scale for serious painting. The “touch” was always there. If you think color is difficult to talk about, try writing about tactility. It is not just a way of putting down paint; it is not just texture. It can also include the way the weight of the paint moves. In Mitchell, touch is vision, is ocular, curiously resplendent. She admired van Gogh and it shows. He too confused light and texture and color in a kind of grand synesthesia. He was the first, I think, to do that. Later, Mitchell may have been the first to do that with abstraction. De Kooning had tactility; Pollock had grandeur. But Mitchell had color, tactility, and light.

And she knew when and where to leave the canvas blank. So there is air as well as space. The relations between paint and canvas (or ground) are complex. Not Asian, not Western; purely Mitchellian. Her “trees” are not pictures of trees but meditations upon treeness, upon stature, upon growth and motion.

Her use of polyptychs (diptychs, triptych and quadriptychs) leaves her open to narrative. But could she help it if she never had quite enough studio wall-space to achieve the scale she wanted? The miracle is that she worked at the panels separately and that they usually fitted together in a thrilling way.

We know she was afflicted with or blessed by synesthesia, but did she also have an eidetic memory? Does a photographic memory include a memory for colors? She mostly worked at night under artificial light and always felt she had to check the colors by daylight.

As a teenager she was a champion figure-skater. That kind of stamina probably stayed with her, for it shows in her paintings. They are, so to speak, energy personified.

But they are also insoucient.

Rage Against the Norm

I read with great interest “Joan Mitchell, A Rage to Paint” by Linda Nochlin in the catalog for the Whitney 2002 survey. Art historian and feminist Nochlin brings up the question of rage and anger, projecting that the paintings are pretty much all about rage. Certainly, Mitchell had a lot of anger and was not a coward about expressing it. Was she enraged by how she was treated as a woman artist? If she felt anger about not being taken seriously as an artist because she was a woman, she was not alone. However, she can never be accused of being a feminist.

She was one of the few women members of The Club in the 10th Street/Cedar Bar days. In some ways, she was one of the boys. She swore, she drank to excess. Just about the only thing she didn’t do was throw Franz Kline or a door through a barroom window. She had some women friends, but few of them were artists. She could be fiercely competitive. For Tucker’s 1974 Whitney show, she refused to share the spotlight with Lee Krasner. Actually, I don’t blame her. Mitchell is by far Krasner’s superior.

Nochlin makes the usual mistake. What you see tells you what went in. If the painting looks angry – for whatever reason — then it was made in anger. An angry painting was made when the artist was angry. But there is another way of looking at things.

I myself find that when I am making a painting I have no emotion in mind. The painting itself creates the emotion. I discover the emotions and the feelings through the painting. Sometimes it is an emotion or a feeling I never knew I had in me; sometimes it is an emotion or a feeling that is totally alien.

The equation is not E/F = P; but P = E/F.

The emotion or the feeling may come after the painting, not before. In Alfred Gell’s anthropological terms, the painting looks at me. I will go further. In my studio, the painting creates me.

It is not that emotions (rage, anger, joy, reverence) are translated into paint. It is instead that the paint causes emotions in the artist and thence in the viewer — combinations of emotions and sometimes the creation of unknown emotions and feelings.

Does the same equation work for ideas? Yes. Ideas do not cause paintings, or if so, only bad paintings. Real paintings generate rather than illustrate ideas. Surely, I learn about myself through my paintings; but more important, I learn about the world.

We have no idea if Mitchell learned anything from her painting. She loved poetry and had many poet friends. Her wealthy mother, in fact, had been co-editor of Poetry Magazine, which had featured the likes of Ezra Pound, Hart Crane, and Wallace Stevens. But Mitchell herself was not given to poetic utterances. The closest I can find is this:

“Music, poems, landscape and dogs make me want to paint. And painting is what allows me to survive.”

John Perreault is on Facebook, specializing in neo-modern, small-scale residential architecture. Links here for John Perreault’s website & John Perreault’s art.

John Perreault videos: http://tinyurl.com/n6x848h