[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”WMFKLc722uPh42qXcoRN8bcevQF4adO5″]

Is Lygia Clark’s oeuvre another case of the oeuvre with a caesura? If so, Clark (1920-1988) got it backwards. You are supposed to start out avant-garde, like some artists I dare not name, and then end up producing Almost Art. It look like art, it smells like art, but something is missing. At least it is saleable.

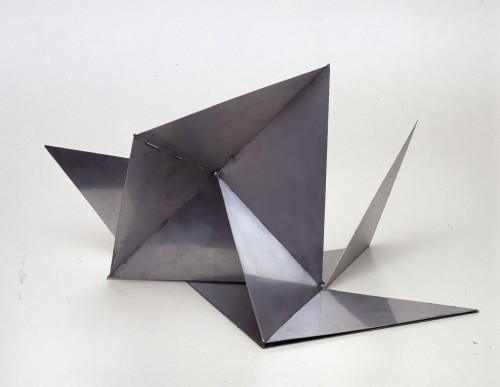

Clark, a goddess of the avant-garde, started out with decades of Almost Art. Then after she abandoned art, she ended up with spiritualized, therapeutic non-art that has more art in it than anything she had done before. Even the sculptures she called “bichos” (“critters”), the direct antecedents to her participatory breakthrough, were variable but not viable. They are so non-haptic that they make Calder (certainly an influence) seem warm and cuddly. Hinged metal shapes with sharp metal edges are not an inducement to play.

The MoMA survey, titled “Lygia Clark: The Abandonment of Art” (to Aug. 24), follows Brit-crit Guy Brett’s pioneering 1994 Art in America article “Lygia Clark: In Search of the Body,” and is even more noncritical. At MoMA, almost three-quarters of the “art” is that which came before Clark “abandoned” art. The abstract paintings and variable sculptures distract from the “non-art” — the participatory rituals that are true art and so over the top that we don’t as yet have adequate language for them. Fewer, more carefully selected examples of Clark’s Almost Art would have sufficed. As it is, much of the show look like the result of the curatorial “will to completion.” The CWTC requires that every work that can be borrowed is borrowed, thus filling huge amounts of space but avoiding critical decisions.

By the way, why did it take MoMA two decades to catch up with Art in America?

Answer: If participatory art is still not de rigueur, Performance Art now is, and we can thereby sidestep pondering Therapy Art and Spiritual Tech if we care to. They are, after all, only subsets of Performance Art, right?

Although she had studied with the great Brazilian landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx, Clark’s early, architecture-inspired abstract paintings are, to put it kindly, tasteful. Looks like she was a bad student. Consider Marx’s swirling Copacabana Beach promenade or his Brasília gardens. Far from tasteful, these works gave a new meaning to Marxism; in enlightened quarters it means gardening with zest and excess.

Clark’s abstract paintings, however, like everything else of hers until Therapeutic Art, are tepid Cubism or Constructivism, influenced by Swiss artist/designer Max Bill of Ulm. He has a lot to answer for. You cannot blame the avant-garde Brazilians of the period for wanting to be international, but Max Bill? Even the Neo-Concretism that Clark and Hélio Oticica (a remarkable artist in his own right) had co-founded does not live up to its promise of participatory, organic art.

Rio is not Ulm. And Clark’s hinged, variable “critters” do not quite deliver. The paper models in a case are better and, in contrast, highlight the big flaw of the hinged sculptures. These studies, even under glass, are tactile; the “critters” are not.

Tropicalism? It is all too cool, even after you get rid of whatever your preconceptions of what tropical art might be. Oticica went on to make very uncool but quite wonderful “nests,” one of which was in the 1970 “Information” show at MoMA. Clark went on to become a legend.

The Lady or the Tiger?

Which way should we enter the exhibition? Through the door that leads to the chronological display? Or through the big, graphic entrance that leads directly to the major, participatory work?

Clark’s late, great work, unlike what led up to it or stood in its way, is supremely tactile, so much so that it is nearly unmuseumable. The works preceding the astounding last room of the survey are an indication of how great the struggle must have been in the then culturally conservative and politically repressive Brazil. Fear was internalized — unless, like Clark, you had the means to move to Paris.

Duchampian Lesson: You have to give up art in order to make art. Otherwise you are merely repeating what you have been taught. Or you yourself taught. Or saw in the art magazines of yore.

Also, it appears you have to make decades of saleable art in order to have your far-out, non-saleable art preserved or even acknowledged. I hope this is not true!

But if there had not been decades of Clark’s Almost Art, there would have been no rupture, no rapture. Without the Almost Art there would be no story. Without a story, no myth.

After Art

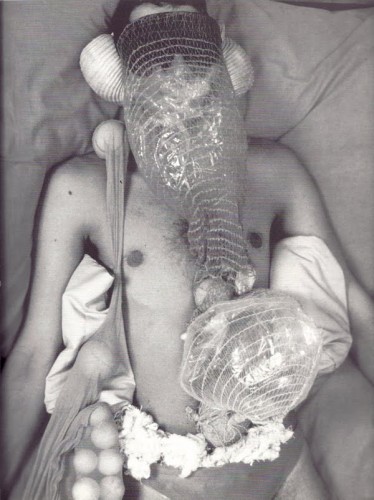

What we have in the last room of the Lygia Clark exhibition are photos, texts and souvenirs. Devices for hearing your own breathing. Hoods. Goggles to distort vision. Pictures of participants wrapped in wet string or gauze. Stones on breath-inflated plastic bags…pebbles on various parts of the body and on closed eyelids….What we have is legend.

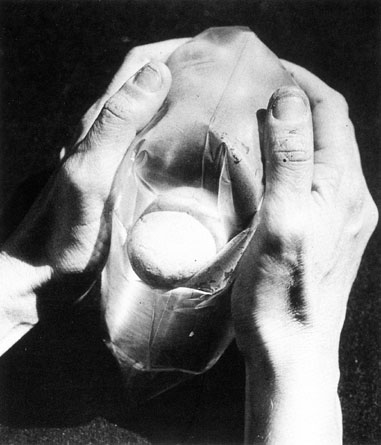

But here is a clue from the 1994 article by Brett. It is about Clark’s Baba antropofágica [Cannibalistic Drool], (1973?) :

A group of people again surround an individual and, holding cotton reels inside their mouths, they continuously pull the thread from their mouths and allow it to fall upon the person lying in their midst, eventually covering the entire body.

Clark reports:

The idea is that a person “vomits” life experience when taking part in proposition. Thus vomit is going to be swallowed by others, who will immediately “vomit” their inner content too. It is therefore an exchange of psychic qualities and the word communication is too weak to express what happens in the group.

Other Paradoxes

Now that museums have destroyed Performance Art, what can they ruin next? If some of the best art of this 21st century is not painting or sculpture — which seems to be the MoMA gambit — how is it be preserved or even presented to the public after the event? Is video adequate? Will there be constant recreations with decrepit art stars straining against age, or paid actors? Will each reiteration be slightly diminished, slightly misinterpreted until strings of new works disguised as old works are created with hardly any relationship to their origins? And who, besides myself, will keep Performance Art separated from bad theater?

Do we need new forms of art built to accommodate transmogrification, warpings and reimaginings? Can we see Performance Art as a virus that rapidly mutates?

To conceive the art museum of the future, we might imagine what a museum of modern and postmodern dance would be. Ephemera, scores, videos, interviews, reperformances? Hardly seems adequate to those of us who witnessed Judson Church dance.

And So It Goes

MoMA really tries to communicate the latter-day Clark. In the room filled with tabletop “critters,” there are actually two variable sculptures you can manipulate under the gaze of friendly guards. In the Clark Triumphant Room, a play-station with objects you may touch and manipulate (with the help of two facilitators) offers much more of the tactile, haptic, participatory.

There is too much to read and a lot of photos. More elaborate participatory events are scheduled now and then, but away from the exhibition space. To be truthful, it really takes a leap of imagination to “get” the work.

One week after the opening of the exhibition, the catalog was out of stock. Could it be that the catalog and perhaps the ancient article in Art in America are better at communicating the art than the exhibition? It may be that exhibitions, just like painting and sculpture, are so last century.

A Strange Meeting in New York City

I met Clark once. It was when I was wary of participatory art or anything like it. We did not approve of the Esalen Institute: We did not approve of all things Californian. We even hated the Living Theater.

It was in the ‘70s, when the infamous French art critic Pierre Restany – he who “discovered” and promoted Yves Klein (and the entire School of Nice) – was shepherding Clark around the New York art world. Clark was in exile from her native Brazil. It was the era of the bad generals and of their 1968 Institutional Act Number 5 (aka A/5) that legalized onerous censorship of the arts in Brazil as well as almost everything else.

I have an artist friend who left Argentina because of the “disappeared” phenomenon — persons eliminated in the middle of the night for their so-called political tendencies. He had a few happy moments on the beaches of Rio, but soon found out that, although they had less garish uniforms, the generals in Brazil were almost as evil as the ones down in Argentina.

When I was introduced to her by Restany, Saint Lygia was teaching at the Sorbonne and, I now find out, undergoing psychoanalysis because of a personal crisis of some sort. Sounds like a classic meltdown.

Another Famous Meltdown

In this regard – and as an aside that is not really an aside — I have recently become taken with the handsome, aristocratic, self-taught Italian composer Giacinto Scelsi (1905-1988). After his wife left him in 1959, Scelsi had a breakdown and turned to Eastern spirituality and Theosophy. In 2005, Alex Ross wrote in the New Yorker:

After the Second World War, he suffered a breakdown and stopped composing for a few years. He spent day after day playing a single note on the piano. The casual observer might have thought that he had gone mad. He was, in fact, finding his path.

Thus, Count Scelsi developed single-note compositions – dictated to him from on high — and then redacted them into scores by a hired hand. First he used a piano to compose, then something called the ondiola. He meant these pieces – the best-known of which is Four Pieces on a Single Note (1959) — to communicate a transcendent reality. My favorites, though, are the complete works for double bass. Performed, they are almost guaranteed to produce carpal-tunnel syndrome in the poor bassist. Once the sounds tune your ears, however, you will easily dismiss the accusation that Scelsi owed everything to György Ligeti (whose Atmosphères was part of the score for 2001) or, on the other hand, that he was the father of Drone Music, and other half-truths. In comparison to Scelsi, Ligeti is quite corny. In terms of Drone Music, did La Monte Young know of Scelsi? In comparison to Scelsi, Young is Baroque.

The musician Scelsi hired to turn his “improvisations” into scores (Vieri Tosatti) maintained that his employer was a fraud and that he himself was the composer of the works. Surely there is some interpretation involved in transcription, but claiming that transcription is composition is irrational. It is almost like claiming the program you use to download music from Amazon is the composer, and not Mozart or — Scelsi. In any case, should it turn out that Scelsi’s works were composed by someone else, that would also be quite a story. But the music would not change. It would be equally unearthly and totally strange.

Clark’s Virtue

After her meltdown Clark moved her participatory impulse out of variable sculptures into life and into a kind of touchy-feely art therapy with spiritual roots. If you have somehow forgotten, the art world used to ban both spirituality and art therapy. Not pure enough. Nowadays, of course, Marina Abramović is peddling her own brand of attentiveness therapy, first to Lady Gaga, now to the world.

I am not quite sure that jolly Restany discovered magus Yves Klein. I never met St. Yves, but from what I can deduce it was probably he who discovered Restany and, as a Rosicrucian and judo black-belt, sent him on his road to Tibetan Buddhism and a book about the Dalai Lama.

In any case, my contact with Saint Lygia was “ether-ial.” I do not speak Portuguese. She did not speak English. She shook hands with people. We shook hands. I assumed this was an artwork. She was a well-turned-out woman wearing ladylike gloves, but she had the force, the charisma, the virtue.

“Virtue” is a synonym for energy, life-force, vitality, mojo as well as the good behavior and moderation recommended by Plato and Aristotle. It is also the term for a rank of angels.

I should have known this. But I was attempting to read John Buchan’s dreary The Gap in the Curtain (Buchan wrote The 39 Steps) when I came upon this (to me) odd use of the word: “… his experiment was draining his scanty strength. The virtue was going out of him into us.” His virility, his Vril, his aura?

Later, when I first visited Brazil, Clark was already a living legend. I was informed by Brazilian sources that in her psychotherapy practice she was using techniques learned from indigenous shamans – wrapping her patients in string and gauze, laying stones on their eyelids and upon mystic pressure-points. I did not even attempt to contact her, figuring that she did not want to be dragged back into the very art world she had transcended. Big mistake. For now she has arrived, with bells — and pebbles and gauze.

Art museums, if they remain on their toes, can handle transcendent art. They are already churches. Some, like MoMA, are big enough and rich enough to be cathedrals. Challenging art, in both senses, is now what they have to be about. How else can they keep the customers coming? How else can they fulfill their duties to culture, criticism and art history? Acknowledgement of Clark’s genius has been a long time coming, but just remember this: Yesterday’s Lygia Clark is tomorrow’s van Gogh.

![Baba antropofágica [Cannibalistic Drool], (1973?), Lygia Clark.](https://www.artsjournal.com/artopia/wp/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Lygia-Clark-Baba-antropofágica-19731.jpg)