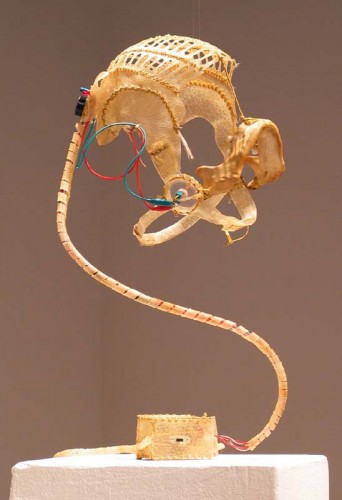

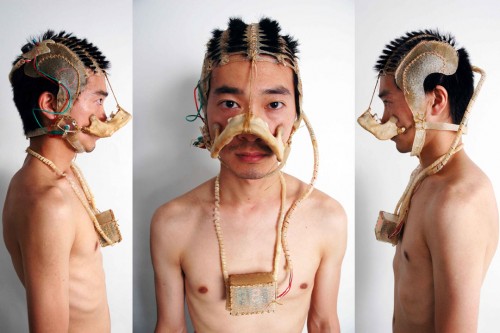

Food was first. Slow Food is the alternative to fast food and agribusiness. Slow food is regional. Proponents of Slow Food call themselves locavores. Slow Food does not mean slow cooking or chewing each mouthful 17 times. Horace Fletcher (1849-1919) once took 45 minutes to Fletcherize an apple. A contemporary version of tech-aided Fletcherizing has been produced in Japan — Masticator (2005) by artist Takehito Etani. It is part of his “Spiritual Prothtetics Series.” It bleeps and flashes with each chew.

Learning How To Watch Paint Dry

Performance Art doyen Marina Abramović, apparently in her New Age phase, has begun promoting Slow Art, the subject of her Marina Abramović Institute, up the river. Endurance Art, as she calls it, to be presented in Hudson, New York, must last at least three hours and will — here’s the catch — require Marina training first.

Three years ago Abramović sat on a chair in the MoMA Atrium. One at a time, visitors sat across from her during her in-depth retrospective — for a total of 716 hours and 30 minutes.

She stared. Each visitor stared back for as long as he or she could stand it. There were huge waiting lines.

“When I stood up from the chair, I was changed,” she said in an interview last month, speaking of the moment she rose to her feet at the end of The Artist Is Present.

“I knew long duration was the answer to everything for me. And, with this, came the idea of the institute in the most clear form.”

The Extended Gaze

And now, it’s time for Slow Art History. I found this out through a posting on Facebook. Will you believe me now when I say Facebook is not just kittens-on-the-keys or selfies?

Harvard art historian Jennifer L. Roberts’ short talk called “The Power of Patience: Teaching Students the Value of Deceleration and Immersive Attention” might change the way you look at art. Or teach it:

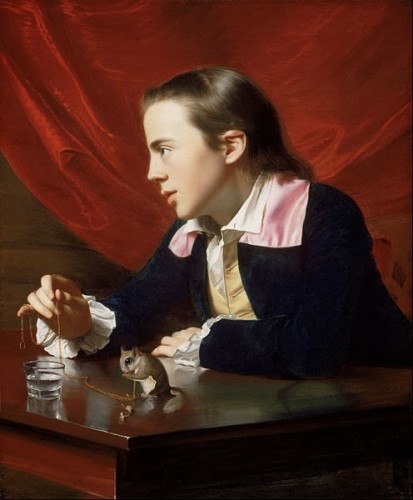

Say a student wanted to explore the work popularly known as Boy with a Squirrel, painted in Boston in 1765 by the young artist John Singleton Copley. Before doing any research in books or online, the student would spend three full hours looking at the painting, noting down his or her evolving observations as well as the questions and speculations that arise from those observations. The time span is explicitly designed to seem excessive.

Roberts did a similar thing herself, and we are privy to the results of her own slow-looking. “It took me nine minutes to notice,” she says, “that the shape of the boy’s ear precisely echoes that of the ruff along the squirrel’s bell — and that Copley was making some kind of connection between the animal and the human body and the sensory capacities of each.”

Although she pays attention to formal devices, she is not a formalist. Clearly she was searching for meanings.

We are looking forward to her timely book, available next February from University of California Press. It is called Transporting Visions: The Movement of Images in Early America, “a material history of visual communication from 1760 to 1860. It focuses on works by Copley, John James Audubon, and Asher B. Durand.”

The only problem with the slow-looking assignment is that you might be able to spend three hours looking at a painting at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, but how about in New York? Try looking at any painting at the Met or at MoMA for three hours. You can’t. There are too many people. Too much hubbub. Guards will immediately become suspicious and begin asking you if you are OK, which is always a sign you are in big trouble. For New Yorkers, Roberts’ pedagogical exercise is, excuse me, academic.

My better half, however, immediately pointed out that away from an artwork you can also think about it for three hours. Does that count?

Certainly, three hours of thinking about a Conceptual artwork will more than suffice, but this may be impossible with an absent painting, unless you have superior image- retention. I wonder if looking at a reproduction or at a Google image for three hours works the same magic as parking yourself in front of a painting in a museum.

Roberts cites art historian David Joselit, who says artworks are time batteries, “deep reservoirs of temporal experience.” Therefore, if may follow that the longer you look, the more you will see.

But perhaps not all “art” will yield results, as did Roberts’ revelatory examination of Copley’s painting.

In comparison to high-speed art, a Pollock, a de Kooning, a Rauschenberg can be savored for at least three hours. A Magritte? Judging by the show presently at MoMA, 10 seconds is more than enough. Besides, you’ve seen it all before, since you were 12 years old, through advertising and illustration knockoffs and highly saturated pictures in books and magazines, where, alas, his paintings are at their best.

Does the time it takes to make an artwork dictate the time it takes to see it and understand it? I doubt it. How much time did it take Duchamp to “make” his Readymades?

How much time did it take Andy Warhol to make his Marilyns?

Can you get more out of a Koons beyond the 10 seconds it takes to get the joke? Or a Damien Hirst? Or a Chris Burden? We now want high-speed art for a high-speed world. Camera-ready, waiting to be packed and shipped to your private warehouse at the Shanghai airport, where it will rest in obscurity while its image circulates the world. If art is supposed to reflect its times, is there anything wrong with instant art?

Excuse me. I thought art was supposed to change the times. Or at least change art.

On a Slow Boat Up the Norwegian Coast

And what about slow TV?

At first, as published in The Chicago Maroon, I thought this was a hoax. No, it’s true. NBK, the public television station of Norway, has been breaking the time barrier. First, it was the eight-hour train ride from Bergen to Oslo, live on TV. One thing led to another. Two-and-a-half million Norwegians watched Hurtigruten-Minute by Minute, the 134-hour live broadcast of a boat trip up the Norwegian coast. Most recently, 18 hours of salmon swimming upstream has proved super-popular, amid complaints that the program wasn’t long enough.

What U.S. live-TV epic could equal or even beat Norwegian Slow TV? Train or car from N.Y. to L.A.? Well, not really. Auto takes only 96 hours. How about peddling or walking to Los Angeles? How about rowing or swimming to L.A. via the Panama Canal?

In the meantime, live cams are readily available on the Internet. We think they are just as good as live TV, and perhaps superior.

Warning: Make sure you get live streaming, not refreshed. And you may have to put up with some advertising. If it’s nightime in San Diego or Maui, you won’t see much. Wait for daylight in whatever zone you are spying on.

Here are some cams you can start with:

You see what I mean? Certain live cams are just as engrossing as Andy Warhol’s eight-hour Empire (1964) showing nothing but the Empire State Building. Maybe live cams are not as transcendent at Bela Tarr’s seven-and-a-half-hour Satantango (1994) or Gregory Markopoulos’s 80-hour Eniaios, which he thought would require a special theater all of its own. But since live cams are live, we go beyond cinema and the TV yule log to something that really is Reality TV, framed but unedited and potentially endless, a kind of flat kinetic sculpture with hundreds of tiny little movements.

Think of how much more artistic the TV yule log would be if it were a live cam. We may never see Santa come down the chimney, but maybe a spark will hit the lens; maybe the fire will go out. Maybe if you turn on to Windansea in San Diego or Sugar Beach in Maui you will actually see the perfect wave.

John Perreault is on Facebook. Links for John Perreault website & John Perreault’s art.