“Chris Burden: Extreme Measures” is now at the New Museum to January 12. Burden has what looks like a bifurcated career, an oeuvre with a caesura. There’s the Burden of daredevil performance art, and then the sculptor Burden who famously makes outsize boys-toys.

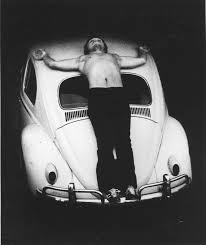

The iconic performances, in case you have forgotten, are Shoot, 1971, having himself shot in the arm and Transfixed, 1974, having himself nailed to the hood of a Volkswagen.

Although some sense of his 54 pioneering performances, done between 1971 and 1977, can be gleaned from loose-leaf notebooks on the New Museum’s fifth floor, it is the latter-day Infantilismo Burden, Kinderkuntz Burden that is featured in the survey.

Three of my favorite Burden’s are so large and site-specific — and in one case so ephemeral — no survey could include them. Here they are:

Less Is More?

Burden is an odd choice for the The New Museum, founded by the late Marcia Tucker in 1977 to highlight emerging and under-recognized artists. Burden is neither.

But museums are allowed to change, even if it means losing whatever distinctiveness they once had. Not so long ago, the NewMu, previously devoted to American art, went international with curiously mixed results. Yes, art is international, but apparently taste is not.

On the plus side, Burden’s sculptures transform the NewMu into something that actually resembles a 21st-century art venue, meaning one or another of the blue-chip galleries in Chelsea that have imitated the pioneering Dia chic of minimalist installations.

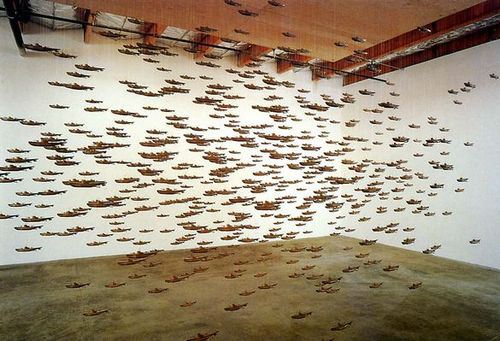

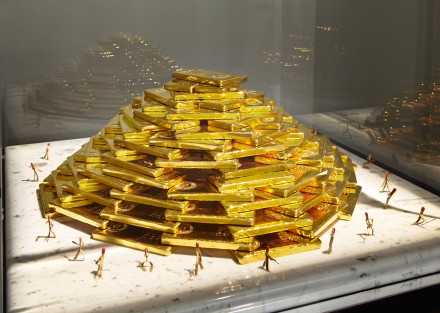

The big Burden boys’ toys are skillfully chosen and perfectly installed. Most notable are the cardboard submarines, the embattled toy soldiers, and the Erector Set displays. There is breathing room around each item or array. The sculptures/installations hold the space, transforming it.

But on immediately begins to ask why is boyhood such a generative source for male artists. Is it the Peter Pan syndrome? Too much therapy? Or because adulthood never comes or, when it arrives, is distasteful? Full of responsibilities and disappointments?

Or — and this idea will drive you crazy — is it because suburbia offers no other subjects?

Nevertheless, the show is an opportunity – long forthcoming – for us to get a handle on Burden Part Two. Perhaps the New Museum should now be devoted to mid- and late-career surveys of artists that the Museum of Modern Art uptown seems unwilling to countenance. MoMA owns Medusa’s Head, 1971, a video of some of his performances, and a print portfolio. Surely Burden could handle the MoMA atrium.

From Dare-Devil Art to Kinderkunst

Burden’s shift took place on or about 1977. Age conquers all. Is risk-taking performance only a youngster’s art? How do you follow up on high drama? Worse yet, how do you make a living? Reality sets in, or teaching.

According to a review by Roberta Smith in the New York Times, Burden “had always considered his performances sculptures, and now he turned to making sculpture that he saw as performances: feats or demonstrations that delved more deeply into reality with forms other than his body.”

Really? Believe That and You Will Believe Anything.

In the MoMA-collection notes for Burden, quoted in Grove Art Online (2009), John-Paul Stonard offers: INDENT

In 1978 Burden was appointed professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, and moved away from performance to an involvement with installation, informed by his interest in technology and engineering. The violence of his earlier performance found a new outlet in his reflections on power politics… Burden’s empirical investigations, characterized by periods of research, development and production, are intended to expose the ills of modern society; through an abstracted technology placed in the service of art, his work provides symbols of redemption and liberation.

Redemption and liberation? Believe That and You Will Believe Anything.

The Oeuvre Caesura in Perspective

The same switcheroo can be seen in the careers of Vito Acconci, Dennis Oppenheim and Scott Burton. Poet Vito Hannibal Acconci turned from extreme performances to sculpture and then to architecture. Oppenheim moved from documented events and Earth Art to wacky sculptures. Scott Burton moved from Street Works to performances to furniture sculpture. What caused this?

Acconci, Burden, Burton and Oppenheim, like most of the Happenings artists before them (who became Pop Artists), switched entirely from one form to another, leaving performance behind. Only the man who named Happenings, Allan Kaprow, did not become a Pop Artist, did not change props into products. But Happenings were more theater than anything else; the artist-playwright was not the physical center, was not the body on display. The exception that proves the rule is, of course, Carolee Schneeman.

Performance Art for one brief moment wasn’t merely a form descended from Futurist Theater and Happenings, but a revolution against the art object, in some ways more radical than Conceptual Art. In New York, Street Works and performances comprised a protest against the poetry reading, print-bound poetry, theater, and the art world.

As a participant in that moment, I can testify that it was an either/or situation. When my own work verged upon traditional theater, I stopped. My last work was Oedipus, A New Work (1972). I performed metaphors inspired by the Sophocles play, i.e. red paint streaming from my eyes, I threw stones at three mirrors. The script was published by The Drama Review, edited by Happenings chronicler Michael Kirby. Performances that required formal audiences had become theater! This is where the RoseLee Goldberg’s distorted history of contemporary Performance Art begins.

An Introduction to 21st Century Art

Once upon a time in the last century you were not allowed to make Blue Period paintings when everyone knew you had started making Cubist ones. And if you moved on to Surrealism, you had to stop your Cubist efforts. If you were an Action Painter, you couldn’t also make or go back to making pro-labor murals. That was way back in the 20th century. St. Jackson had a hard time when he began to reintroduce the figure. Whereas St. Marcel, always under the radar, got away with everything.

The change in the 21st century is that artists are now allowed to juggle various styles and genres, to zigzag back and forth to a degree that would have made even Picabia dizzy.

Although “superstars” Damien Hirst and Richard Prince do not exactly juggle genres, they certainly float various product lines. Hirst’s dot paintings, spin paintings, medicine cabinets, butterflies and animal vitrines exist simultaneously within the Hirst Corporation in much the same way that General Motors offered Chevys, Pontiacs, Oldsmobiles, Buicks and Cadillacs. Prince is more modest; so far he juggles Marlboro cowboys, jokes and paperback nurses.

It is no longer suspect when an artist offers works in various genres: painting, sculpture, performance, installations, video. In fact, in Art School Art it is expected. You are being groomed to be a latter-day Picasso or Beuys. What, no video? Didn’t you go to art school?

The Burden bifurcation is so last century.

Is Burden’s split a kind of mirror image, as he himself seems to think? Are the performances about space? The sculptures about performance? I cannot really see all his performances as about space. Getting caged in a locker, maybe. Nailed to a Volkswagen? Never.

And, let’s face it, Erector Set constructions (or a case of components), masses of toy soldiers arranged as if at war and a car balancing a meteorite may exist in the realm of play, but they do not exactly join the realm of performance.

Objects don’t perform. They may be made to demonstrate one physical principle or another (as at a science fair), they may be stand-ins for the artist, but they themselves are not performers. We must not confuse performance, as in a “high performance automobile,” with performance in Performance Art, in which the body of the artist must be present, rather than merely represented.

What is consistent on both sides of the Burden divide is a certain aloofness. Even having himself shot in the arm had an unlikeable cool. His chilly sculptures demonstrate simple physics and enlarged Boy’s Mechanics projects.

A studied ambiguity carries over the fold.

Is having yourself shot in the arm a Vietnam protest or masochism? Are the toy soldiers of A Tale of Two Cities (1981) or the swarm of cardboard submarines that make up All the Submarines of the United States America (1987) anti-war or a glorification? What are we supposed to think? Does our culture turn boys into would-be warriors or are boys themselves innately warmongers? Or are Burden’s Boys’ Toys merely the precedent for the Kinderkunst and Infantilismo of Jeff Koons’ balloon sculptures and Mike Kelley’s stuffed animals?

John Perreault is on Facebook. Links for John Perreault website & John Perreault’s art.