Love in the Afternoon

To understand contemporary art you must mis-understand Marcel Duchamp. The readymade is the template for all things postmodern. But how do you choose which store-bought object to sign? The broken and mended Bride Stripped Bare by Bachelors, Even is the clue to the real meaning of the readymades. The readymades, including most famously the signed urinal, the bicycle wheel, and the bottle rack are idols of the marketplace. They are symbols.

And thus we come to Papa Dada’s redemption as an occultist and the unraveling of all things given, taught, copied — to be replaced by the cosmic/erotic, mechanical/mystical remythification of art.

At least in Artopia, which is the only reality worth taking seriously.

Did not Duchamp write: “To all appearances, the artist acts like a mediumistic being who, from the labyrinth beyond time and space seeks his way out to a clearing.”

In Artopia we think of Duchamp as one of the great poets of the last century; perhaps too much of a dandy, perhaps too much of a chess-player and a poseur, perhaps too much of a gentlemen — but always a prestidigitator of the first order.

THE

If you come into * linen, your time is thirsty because * ink saw some wood intelligent enough to get giddiness from a sister. However, even it should be smilable to shut * hair whose * water writes always in * plural, they have avoided * frequency, meaning mother in law; * powder will take a chance; and * road could try……

Replace each * with the word: the.

(Marcel Duchamp, 1916)

So by all means read Marcel Duchamp: The Afternoon Interviews by Calvin Tomkins (Badlands Unlimited, Brooklyn, 2013) if you must. Tomkins seems to have been in the habit of visiting Papa Dada, with a tape recorder in hand. In 1964. The interviews, embalmed in the MoMA Library, have never been transcribe, edited and published before. Alas, you will not learn anything new — unless, that is, you have not read anything about Duchamp before, including Tomkins’ info-packed Duchamp: A Biography (1996).

Wait. I did learn two new things from this slim offering: Duchamp could be very boring, particularly when explaining why artworks should take a long time to make — like his two masterpieces, the unfinished The Bride Stripped Bare by Bachelor, Even and the posthumous Given: The Illuminating Gas. How self-serving. How old-fashioned. I think the faster the better. I make my new big paintings in 8 minutes flat. When asked how long they take me to make I say eight minutes and 55 years. That’s how long I have been studying art and, in both senses of the word, practicing.

The second thing I learned is that the master himself preferred Robert Rauschenberg to Jasper Johns. In this regards, Duchamp is still ahead of the curve. Rauschenberg is one of those artists who will look better and better the further we get away from him. Is this because he was generous, energetic, and convivial? More like nature than like scripture? Whereas Johns, I fear, worshipped by so many for his intellect, may not fare so well. Too dry.

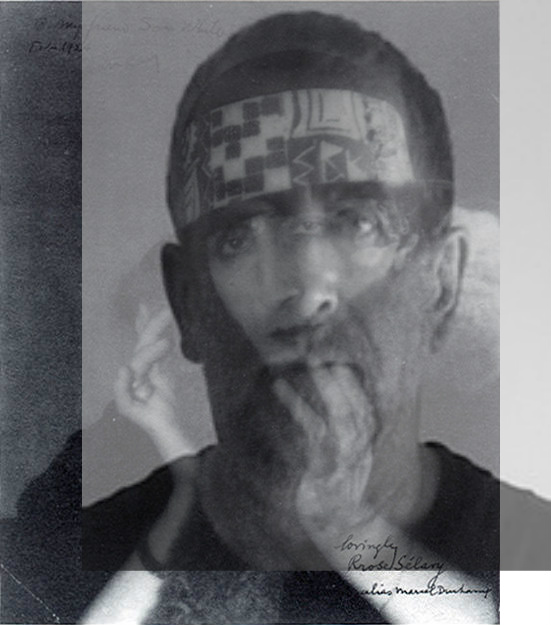

Tomkins does not ask Marcel if his alter-ego Rrose Sélavy was his Jungian anima. Had he read Jung? Who was Marcel channeling? Was he conversant with the Kabbalah, Christian or otherwise? And on the literary front, had he ever met Alfred Jarry? He could have, because he was “studying” art at the Académe Julian in Paris in 1904-05 and Jarry lived until 1907. Did he know the works of that other super-punster, Raymond Roussel, who was also alive in Duchamp’s youth? Did he know any of the descendants of the 19th century Parisian “alchemists” who sponsored August Strindberg’s mad Parisian forays into mystical chemistry? Why did Dada Mama Beatrice Wood run from drawings to ceramics, from Marcel’s charms into the arms of Krishnamurti? Why was she hypnotized by the search for a glaze of gold? But I guess no one asked those kind of things in 1964.

In short, Tomkins didn’t really ask the right questions. Robert Smithson told me he once confronted Duchamp at a party: “I see you are into alchemy,” he accused. “Why, yes,” answered Marcel.

The interview texts are lean. Although not ever published in the New Yorker, they smell of that rag’s triple-edit, editing style. So 20th century.

Speaking of which…

Way back in 1996, yours truly published a Duchamp “interview” which if readers really read they could have deduced would have had to have been conducted many years after his death. Marcel was truly underground, not merely artistically underground. It was upon the occasion of the Whitney’s “Making Mischief: Dada Invades New York” which, of course, was invested with a lot of Duchampiana and was guest-curated by a very distinguished art dealer specializing in Dada. I ventured to say that most of us had already seen the major works, but going to the Whitney was a lot cheaper than training down to Philadelphia, where because of patron Walter Arensberg so much of Duchamp’s oeuvre is interred. That in itself is an interesting story.

Wealthy cryptologist (Francis Bacon was Shakespeare!) Arensberg tried palming off his collection of 36 Duchamps, 19 Brancusis, and 28 Picassos on a West Coast group of art fanciers and then the University of California; even the nascent LACMA rejected the stuff. The Philadelphia Museum of Art, oddly enough, did not, filling all conditions save the founding of a Bacon/Shakespeare research center.

Although I blush to say it, my 1996 review, disguised as a fake interview, is far better than Tompkins’ recently revealed interviews. It certainly is wittier. You can read it HERE.

Postlude: The Will to Completion

I have been pondering the Will to Completion in regard to survey exhibitions. Why must curators (and perhaps their bosses) insist that every retrospective or survey include everything available rather then just the best examples? We see this in the Jay DeFeo exhibition now at the Whitney. Even great artists only produce one or two masterpieces and everything else is experiment, repetition, or treading water. Duchamp may be the one exception since every scrap is fraught with meaning.

Surely completion is the disguise for the need to satisfy markets and collectors, to cement relationships, and to avoid aesthetic decisions. Surely also to objectify the satisfactions of the successful hunt. But worst of all it is caused by the Will to Completion itself, the creator of a Demon of immense power. Postage stamp collectors and collectors of mid-century modern American dinnerware know whereof I speak. In my own case, I have collections of lightning rods, gear-shift knobs, glass transformers and rug-guards. I am always on the look out for more, but I think I may have cornered the market. Is there a Holy Grail of glass rug-guards? I almost started a collection of 45 rpm to 33 1/3 adaptors, but miraculously before I started yet another foolish quest I found someone who had already plugged that hole.

Why do we need to be definitive? The will to completion is probably a sin. Every oriental carpet must have at least one mistake.

More on subject is my library. I count on my bookshelves 12 books about Marcel Duchamp. Isn’t that quite enough? Why do I feel I have to own every book about Marcel Duchamp? I have 32 publications about Andy Warhol. I have more Warhol books than Duchamp books, not because I like Andy more than Marcel, but because there have been more books published. It’s the dreaded Demon of Completion that makes us acquire books that only repeat what has been written before.

This time, however, I fooled the Demon. Almost. Should I buy The Afternoon Interviews or not? I did not buy the ink-on-paper version ($16). I bought the Kindle download ($5.99). Because of Kindle, I am saving shelf space and a lot of money on bookmarks. Never have to buy or build more bookshelves. And I have eluded the ever-present danger of book-mites.

ARTOPIATECTURE: small houses, pods, huts, retreats….