“Gutai: Splendid Playground” (Guggenheim to May 8) forces a rewrite of art history. The co-curators, Alexandra Munroe and Ming Tiampo, in their catalog essays meet the issues head-on. The subject matter demands it, for Gutai is the unfairly scorned post-War Japanese avant-garde movement devoted to the kinaesthetics of painting, the spiritualization of matter, and interactive art.

Kazuo Shiraga made paintings with his bare feet. Saburo Murakami hurled himself through layers of paper. Shōzō Shimamoto threw bottles of paint. Akira Kanayama used remote-controlled robot toys to make etherial drawings on vinyl. These are the true heirs of Jackson Pollock. Not Helen Frankenthaler and Jules Olitski. Why has this authentic descent been repressed?

Munroe, whose Scream Against the Sky (Abrams, 1994) is the standard survey of Post-War Japanese art, charts a bit of Guggenheim history, citing the 1963 Japanese trip of curator Lawrence Alloway. Alloway was the Brit who coined the term Pop Art. He included both Gutai founder Jirō Yoshihara and Atsuko Tanaka in the Guggenheim International Awards exhibition of 1964.

Munroe also outlines the support for Gutai in terms of the Post-War, anti-Soviet propaganda push that used Abstract Expressionism as a symbol of freedom of expression under democracy. Gutai, at least in its kinaesthetic painting phase, was intended to show what could happen in art when totalitarianism, such as that under the wartime Hirohito regime, was removed. Indivdualism was to be the new Japanese motto. Even the artists themselves thought this was a great idea.

In the U.S., however, American artists apparently had little knowledge of how their paintings were being used by the State Department, the United States Information Agency, and perhaps the C.I.A.

Munroe, in an essay that is exceptionally forthright for an exhibition catalog, goes right to the point:

The leading university textbook in use today, Art since 1900, reserves a scant five of its 816 pages to “the dissemination of modernist art through media and its reinterpretation by artists outside the United States and Europe.” The authors cite Gutai and the Brazilian Neo-Concretists but misread both as derivative, disregarding their critical agency. Indeed, their terms “dissemination” and “reinterpretation” preserve the construct of Euro-America as the dominant center and Western modernism as the master narrative, perpetuating a kind of canon that other disciplines have long since dismantled. Such closed, geocentric views of the history of modernism perpetuate the West’s stronghold on avant-garde originality, relegating modern art made outside the putative centers as belated and derivative.

Why Was Gutai Marginalized?

Nationalism? Americanismo and Eurocentricity are not enough to explain the Big Silence. I think the sources of both are racism and the lust for power and profit. This more fully explains, alas, the shunning of Art Informel and Tachisme on this side of the Atlantic, as well as the marginalization of Gutai in both Europe and the U.S.

When I was writing for Artnews in the very early ‘60s, the editor forbade even a mention of Pierre Soulage, Jean Fautrier, George Mathieu, Nicholas de Stael, or Hans Hartung. Jolly Jean Tinguely and Niki de St. Phalle were o.k. I internalized this, but still somehow managed to grab a cover story on Jean Dubuffet. I particularly liked Dubuffet’s championing of Outsider Art and detectected an all-overness in his later paintings that connected to Pollock.

Now, as a painter as much as a critic, I hope I can look at these shunned European artists with new eyes. And at Gutai.

Heirs Apparent

Aspiring to liberate painting from the museum, the wall, the frame and even the paintbrush, Gutai artists moved in radical directions. Early experiments focusing at first on process, investigating a variety of both art and nonart materials, ultimately resulted in “performance paintings” that incorporate time and space into their very being.

Ming Tiampo, Co-curator, Gutai, 2013.

Do what no one has done before!

Jirō Yoshihara, Founder of Gutai, 1955.

The Gutai Art Association was the victim of what in technical terms is called the double-whammy. Gutai (meaning “concreteness” or perhaps “embodiment”) was associated by the N.Y. art establishment with Art Informel, Taschism, and other anti-formal styles in Europe. These were dismissed as being inferior to American Abstract Expressionism, deemed the only ligitimate heir to European modernism. If you could prove paternity then there was money to be made. To put it bluntly, the market had to be cinched; American hegemony had to triumph on the cultural as well as the political and economic fronts.

Exceptionalism and the special mission of America needed to be maintained or once again all hell would break loose.

New York was the new Paris. But even Paris had been fed by and had off-shoots in Munich, Berlin, Amsterdam, Vienna, Moscow. Oh, sorry, we conventiently forgot about that.

Gutai dared to propose that a major art incubator could exist outside Paris or New York, and, yes, even Tokyo. The 59 artists of Gutai were located along the Hanshin Belt between Osaka and Kobe.

The import of Gutai goes on and on. Not only must we obliterate the master narrative, we must look at the situation that Gutai pre-saged: decentralized world culture. Everyone once wondered what the new New York would be. Just as New York became the new Paris, surely New York would eventually be superceded. Sorry, no such thing has happened.

All points on the globe are the same distance from the cloud and thus at no distance from each other. There are auction sites here and there, but there is no Paris. There is no New York. There is no capital of art. Even art museums and galleries whose numbers once could authenticate an art capital are migrating to the web.

Decentering Power

What was Gutai’s secret? The art was sensational. And they had their own magazine to promote the cause. Jackson Pollock himself had two issues of the Gutai magazine in his library when he died. Gutai — for better or worse – reached out and formed alliances with two other artist groups on the so-called periphery — Zero in Dusseldorf and Nul in Amsterdam. There were also connections made with Allan Kaprow, John Cage, Fluxus, and Experiments in Art and Technology. Like Futurism, de Stijl, Constructivism, Dada, and Surrealism, Gutai had an international outreach.

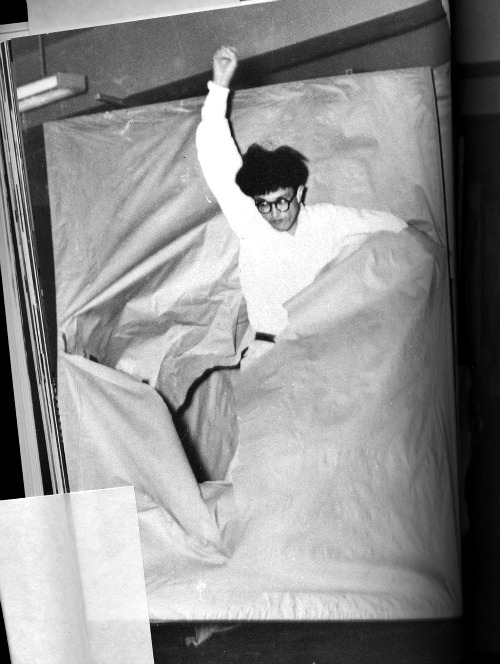

In an era of post-Performance painting, it would serve art well to look at Gutai, which in Phase One proposed no difference between painting and theater and, in fact, predated Kaprow’s first U.S. Happening (1959). Monroe gives as an example Jaurakami Saburō’s paper-penetration Work (Six Holes), 1955, but the catalog reveals even earlier Gutai candidates for world’s first happening/performance.

But we must also find a theoretical basis for global art-culture as it has now formed. The Cold War narrative has proved inaccurate, unhelpful, restrictive, ungenerous, and uninspired, leading to the “death of painting” at the hands of the Greenbergian formalists who championed flat color and their descendents, the Artforumalists, who prefer photography and words to art, forgetting that photography is the mother of all lies and words must be translated.

Gutai One and Two

Both Munroe and co-curator Ming Tiampo, following a Japanese precedent, divide Gutai into two phases. What I am calling Gutai One (1954-1961) and Gutai Two (1962-1972) are as different as Analytical and Synthetic Cubism were. Gutai One is frantic and funky, theatrical; Gutai Two is cool and technological. The dates should not be the only vectors, because works of either kind can occur in Gutai One or Gutai Two.

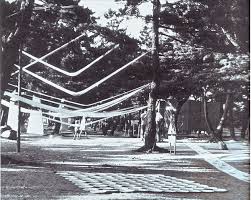

There are two things Gutai One and Gutai Two have in common. The first is that in both the artists courted audience interactivity — in the first period through participatory playgrounds and ad hoc festival art, all of a decidedly low-tech sort; in the second, through technology.

The second characteristic the two periods of Gutai have in common is the attempt to alter cultural situations. Gutai One was definitely an attempt to free the arts in Japan from the nightmare of the Hirohito era, which privileged conformity. Gutai Two, paradoxically, was a response to the sudden hegemony of Japan’s technological surge — not, however, an attack; but, it would appear, an attempt at humanizing it.

Gutai Two failed at art, just as the E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology ) 9 Evenings (1966) did in the U.S . Celebrating technology is like celebrating lunch. On the other hand, to use technology to criticize technology you have to be in bed with the enemy. In the U.S. the love/hate nature of Pop did not transfer to Tech Art, with the possible exception of the funny/scary works of the ingenious Nam Jun Paik.

At the Guggenheim, Yoshida Minoru’s Bisexual Flower (1969) is not engaging; or even amusing. Montonaga Sadamase’s Work (Water), made for an outdoor festival in 1956, now recreated for the Guggenheim rotunda, looks like it is Gutai Two, and that’s not good. In certain kinds of art, time and context are all. Compare the photos here:

After 1962 Gutai came in from the streets and playgrounds. Gutai, now with its own art center, embraced technology and lost a more powerful vision. This Tech Turn produced some really slick stuff. What Gutai gained in internationalism through its alliances with the tech-oriented Zero Group (Dusseldorf) and Nul (Amsterdam), it lost in achievement.

Of course, I am simplifying. Atsuko Tanaka (1932-2005) was active in both phases of Gutai. And, believe me, she is one of the great ones. Electric Dress, 1956, and Work (Bell), 1955, are as technological as anying in Gutai Two; and although her gloriously astringent Work (Yellow Cloth), 1955 –three pieces of commercially dyed, found cloth — transcends both Gutai One and Two, Round on Sand, 1968, a sand drawing on a beach, would fit best in Gutai One

And Shuji Mukai’s Happening: Burning All My Works, 1969, in which he did just that, should be in One not Two.

The Scream of Matter Itself

Yes, indeed; it is time to take a closer look at Gutai.

We know that Pollock’s art was crucial to the founder Yoshihara. He intuited Pollock’s spiritual import by demanding in the Gutai manifesto that art materials be brought to life:

Gutai art does not change the material but brings it to life. Gutai art does not falsify the material. In Gutai art the human spirit and the the material reach out their hands to each other, even though they are otherwise opposed to each other. The material is not absorbed by the spirit. The spirit does not force the material into submission. If one leaves the material as it is, presenting it just as material, then it starts to tell us something and speaks with a mighty voice. Keeping the life of the material alive also means bringing the spirit alive, and lifting up the spirit means leading the material up to the height of the spirit.

Jirō Yoshihara (1905-72)

There’s a thread that needs to be picked up. Painting as performance, restyled as “post-performance painting” is part of contemporary practice. Why was this thread “lost”? Critic Harold Rosenberg almost embraced performance with his Action Painting concept, but buried it under some inept and heavy-handed Existentialism. And after de Kooning he anointed no winners.

Critic Clement Greenberg recycled Gotthold Lessing. Surely we must keep everything neatly separated. During the Cold War, art had to be separated from politics. Lessing’s 1766 dictum that poetry and painting must be kept separate was expanded. Painting, poetry, theater, history, dance, became forms trapped within their own self-referring purity. This leads to some curious results. If you take poetry out of Schoenberg and Webern you get Milton Babbitt. If you take theater, poetry, history, and myth out of painting you get…Jules Olitski, which was exactly the point.

And he was not the worst of Mr. Greenberg’s products.

Is The Theater Really Dead?

How can you not see the theater in both Pollock and de Kooning? Robert Rauschenberg did. Carolee Schneemann did. Allan Kaprow was not the only one smart enough to run with the ball, while others produced confections for board rooms, bored businessmen, and embassies abroad, under the Greenbergian gun.

But isn’t Kaprow Pollock’s most important heir? Just when you get your mind bent around that one, Gutai comes around again .Gutai is an earlier and more cogent heir, since abandoning paintings was never on their menu.

So changes are afoot. We are getting a full dose of revisionism. Mark my word; Gutai will be followed by Art Informel and clearly, since there is a curious essay on Brazilian Concretism and its affinity to Gutai in the catalog, that misunderstood movement also will be regained . Whether or not these correctives are a product of the insatiable art market or the academic meat-grinder, which has similar needs, is not for me to say. I prefer to think it’s a function of justice.

And finally…..

Thus it is our task to rewrite art history. We do, of course, have a new tool. Diagrams are destiny. Change the diagram and you change the world. Instead of a ladder or staircase or even a tree, we should picture a braid with as many strands as we can stand.

Art styles do not follow one another step-by-step or even as an ongoing argument. They disappear and reappear. They twist and turn. They rub up against other styles. They migrate and transmigrate. They pop up in very strange places. As in parapsychology, causality is replaced by synchronicity.

No space.

No time.

No place.

No translation required.

Note: You can download to your iPhone and iPod Touch for free the amazing Guggenheim Gutai educational material, including images and specifications of every artwork in the exhibition. Start by going to: guggenheim.org/apps. And, needless to say, you can do this almost anyplace in the world.

John Perreault is on Facebook and Twitter. John Perreault website. John Perreault’s art. The Artopia Project also includes: artopianews; artopiatecture; thehousedetective ; johnperreault.tumblr. AND pinterest.com/johnperreault1/