“Art of Another Kind: International Abstraction and the Guggenheim, 1949—1960” (Guggenheim Museum to Sept. 12) consists primarily of artworks collected by the Guggenheim before the 1959 opening of its Frank Lloyd Wright building on Fifth Avenue. This odd and in some ways adventurous exhibition is a trip back in time, a survey of works promoted by then director James Johnson Sweeney. Not one to avoid exaggeration, he called the artists he glorified “tastebreakers” or those who “break open and enlarge our artistic frontiers.” The 90 works cascade down or struggle up the spiral ramp, but are broken into two unlabeled sections: Euro and USA. The bookends are Vasarely’s irrelevant Op-Art painting and Jackson Pollock’s small Untitled (Grey and Silver) of 1949, which looks like it was cropped from a larger painting.

Paintings Look Good on the Ramp but Sculpture Doesn’t

As you climb the ramp, the Pollock is the introduction, or, if you elevator to the top and skip your way down, the awful Vasarely sets the tone. Where does the exhibition begin? Where does it end? Which end is up? Always a problem at the Guggenheim.

There’s so much traffic now that if all exhibitions started at the top (as I remember they were meant to), and if the customers knew or were forced to conform, the cozy elevators would not be able to handle the crush.

Vis-à-vis starting at the bottom: someone must think the hike is good exercise or that it slows down the rapid descent compelled, with or without roller-skates, by starting at the top. I should also add that the elevators stop one ramp short of the actual end or beginning, meaning you always have to double back if you want to begin at the very top of the spiral.

The recent John Chamberlain retrospective started at the very top and worked its way down, whereas the groundbreaking “Chaos and Classicism: Art in France, Italy, and Germany, 1918-1936” in 2010 cheerfully slugged its way up the ramp with one awful painting after another. That exhibition ended with the large mural that once graced Adolph Hitler’s dining room, Adolf Ziegler’s campy Four Elements: Fire, Water, and Earth, Air, putting a nail in the coffin of the classicism that roamed both Europe and America between the two world wars of the last century.

By allowing two beginnings (or endings), “Art of Another Kind” splits the difference.

In any case, in either direction, it is difficult to break from the linear and notions of progress or decline. Museum buildings, like proscenium stages, generate scripts. Frames or pathways predetermine meanings. At the Guggenheim, Maurizio Cattelan recently “solved” the problem, but lost the battle, by hanging all of his works in one big chandelier of bad jokes, in what appeared to be an attempt to avoid the lack of development in his oeuvre. Lack of development might be OK if you are Ad Reinhardt or Josef Albers, but he is neither.

In the current exhibition, are we to believe that New York Action Painting led to European Art Informel? Or is it the other way around? Correct answer: neither. If you check the dates, those apparently warring styles were virtually simultaneous. Would it not have been more interesting to present the works juxtaposed, and strictly chronologically? Mixing up the Euros (plus one or two Japanese artists) and the Americans? Then it might be easier to see differences (if any) and similarities (more than were visible at the time).

The Match Was Fixed

Contradicting past-director Sweeney’s more generous, ultimately more accurate vision, “Art of Another Kind” through its caesura perpetuates the postwar division between Euros and Americans created by the self-serving marketing efforts of critics such as Clement Greenberg, Thomas Hess, and Harold Rosenberg. And, I should add, efforts by complicit U.S. curators, collectors and dealers, not to mention artists, who obviously had a stake in this fake boxing match. Alas, most art history textbooks, in the U.S. at least, still toe the line.

The match was fixed. The U.S., specifically New York, was deemed the site of the triumph of abstraction and the next step after Cubism. This was nationalism. This was how we showed the rest of the world we were better than the nasty USSR. And, oh, yes, better than France, Germany, Italy and Japan.

Notwithstanding gems by Willem de Kooning, Robert Rauschenberg, Hans Hofmann, and Pollock, many of the American paintings in the show are as formal and dead as the European successors to the School of Paris that were accused of same. We must look again.

Time changes history, even art history.

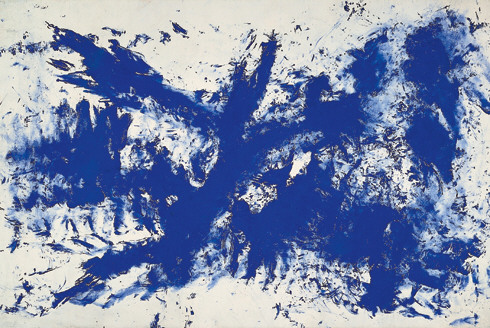

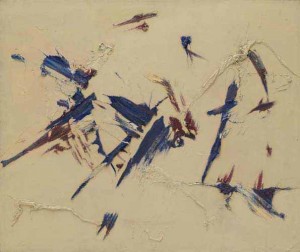

Many of the European paintings on view are not all that bad. It is time to look with new eyes at the work of such artists as Antoni Tápies, Pierre Soulages, Emilio Vedova, ex-Surrealist Judit Reigl, and even the early work of Jean Dubuffet, wine-merchant to the Surrealists. Lucio Fontana, one of the best of the Italians, is already covered by a recent and ever so timely show at Gagosian. At the Guggenheim, Yves Klein’s Large Blue Anthropometry (1960), painted with naked female models coated with International Yves Klein Blue, is wild and as great as any Pollock drip painting. Like the best of Pollock, it was executed on the horizontal and looks like it was made by an animal or an alien from some unknown planet. It blasts a hole in the curved wall of the Guggenheim and punctures art history.

Other Groans and Provisos

Apparently Joan Mitchell was not a “tastebreaker” and was left out. If you want to see a great Mitchell, scoot over to the MOMA lobby just beyond the tolls to see Wood, Wind, No Tuba of 1980. Neither Elaine de Kooning nor Louise Bourgeois were “tastebreakers,” but are included in the Guggenheim’s sampling. Were there no Mitchell’s purchased during the survey window? If not, this points to a fault of time-bound surveys gleaned from a museum’s storage rooms. No one collection is perfect.

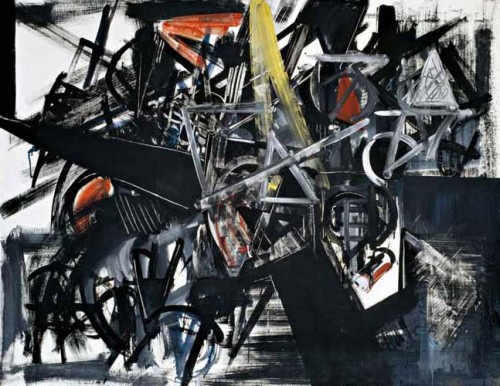

And why, oh why at the Guggenheim do we need the sprinkle of sculptures, perpetuating the MoMA error in its AbEx survey of last year? Reversing my insistence that Action Painting and Art Informel should be united, sculpture and painting of this period should be separated. Please, break the rules. One wonders why Constantin Brancusi’s fine Adam and Eve (1916-21) is included, since he had absolutely nothing to do with Action Painting or Art Informal and also date made rather than date accessed seems to otherwise apply. But there is no excuse at all for Louise Bourgeous’ Femme Volage (1951) or Eduardo Chilida’s From Within (1953). Sculpture, alas, in those exciting days of Action/Informel could not hold a candle to painting — unless you count ceramics-giant Peter Voulkos, which would still be too revolutionary for the art world. Not until Chamberlain do we really get Action or AbEx sculpture. Does a survey of Impressionism or Surrealism or the Ash Can School require sculpture? Certainly not.

For easy access to previous Artopia essays by topics, go to top bar, click on ABOUT, click on ARCHIVE, then scroll down to listing by Headlines.

NEVER MISS AN ARTOPIA ESSAY AGAIN! FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT contact perreault@aol.com

John Perreault is on Facebook and now on Tumblr. You can also follow John Perreault on Twitter: johnperreault. Main John Perreault website. More of John Perreault’s art.