Can artworks survive once they have fallen out of fashion? Or no longer inspire further art? Are off the grid? Are not part of the ongoing dialogue, but come across, if at all, as dead ends? As orphans, bachelors, old maids?

Roberto Matta (1911-2002) at Pace to Jan. 28, Diego Rivera (1886-1957) at MoMA to May 14, and Francis Picabia (1897-1953) at Michael Werner to Jan. 14 were each at one point vital to the art life, so probably deserve a new look.

The Artist’s Artist, the Painter’s Painter

But Edwin Dickinson? When was he central? He didn’t fit into American Scene painting or Modernism. He was not a Dadaist, a Cubist, or a Surrealist. Although he was briefly saved from starvation by the Works Progress Administration’s easel-painting subsidy, he did not produce overt socially conscious art. He certainly never tackled murals. On the other hand, his art was just too strange to be considered academic. Maybe too poetic?

The way art history has been written, he has no heirs. That needs to change. Different times require different views of the past. And different family trees.

Dickinson(1891-1978) is well-worth looking at and thinking about. There are lessons to be learned, particularly if you yourself are that rare thing, a true oddball, lone wolf, keeper of your own secrets, priest or priestess of art rather than of career.

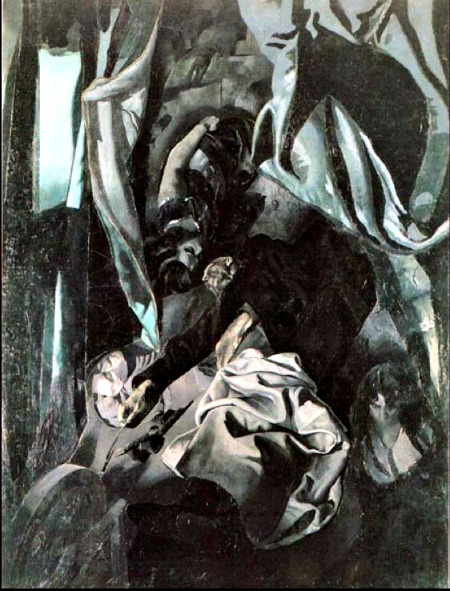

- Dickinson, Frances Foley, 1927. Courtesy Babcock Gallery.

Three Strikes and You Are Out

The Babcock Gallery (774 Fifth Ave., to Jan. 22) is now offering “Edwin Dickinson in Retrospect.” All three faces of Dickinson are sampled: the lovely premier coups (some of them pre-de Kooning action paintings); hints of what went on in his big paintings, but only hints; and the self-portraits.

The premier coups or first strikes are masterful. This method simply requires that mistakes be jettisoned right there on the spot. Doesn’t look right in front of the subject? Scrape it down! The results range from delicate to dynamic.

This comes right out of the Munich tradition. The difference is that Dickinson did not treat his first strikes as outdoor sketches, meant to be used in larger, finished works, but offered them as finished works themselves. They are raw, special. You participate. You not only feel where he was standing in front of his subject and at what angle he was viewing it, but you can identify his movements in applying pigment.

In contrast, the “machines,” or what curator Douglas Dreishpoon and Pollock-expert (!) Francis O’Connor in separate essays persist in calling the “symbolical” paintings in the catalog for “Edwin Dickinson: Dreams and Realities” (Albright-Knox,Buffalo, 2002), are diabolical.

Symbolical as opposed to symbolic, or like the Symbolical Rites of the Masons? Dickinson’s masteful The Fossil Hunters might have been painted by a modern-day El Greco in a severe fit of depression.

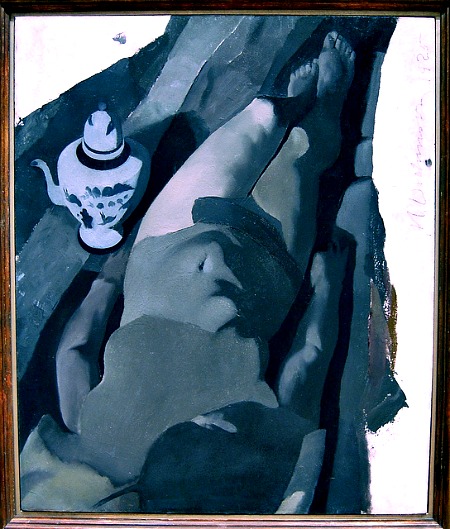

- Dickinson: Locusts Woods and Grass, Truro, 1934. Courtesy Babcock Gallery

The first strikes are about the known, what we can see with our eyes and can jot down with our paint rags, palette knives, and little pinkies (one of Dickinson’s favorite outdoor tools). Here is Dickinson’s philosophy:

“If you do not bring anticipations to the sight of an object when drawing it, anticipations which are connect with associations in your lay life, it is easier to get it right then to get it wrong.”

The machines or the subject paintings or the “winter paintings” done entirely in the studio were also not preplanned, according to Dickinson. He just went ahead. They are about what we cannot know. The angle of vision is either too high or too low; one object blocks another or turns it into a splinter or shard. Bodies are cadavers. And the light is always dimmer than twilight. Stygian. Faces are in shadows or otherwise blurred and incomplete.

The Big Ones: My List of Dickinson Machines

Interior, 1916.

An Anniversary, 1929-21. Albright-Knox,Buffalo,NY

The Cello Player 1924-26. De Young Museum, San Francisco.

[Dickinson’s list of depictions: “14 books; two potatoes; 2 saucers; 3 sheets of music [Intermezzo from Cavalieria Rusticana, violin allegro from Marriage of Figaro]; 2 china pitchers; 7 shells; 1 photograph; 1 trilobite; 3 kettles; 1 rose; 1 music stand; 1 chair; 1 organ; 1 piano, 1 cello….John Cordes…..” Cordes was the model for the cello-player. Dickinson, who did not read music, played the cello by ear.]

The Fossil Hunters, 1926-28. Whitney Museum of Art.

Woodland Scene, 1929-1935.

Composition with Still Life, 1933-37. Museum of Modern Art.

Ruin at Daphne, 1943-53. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

[His last “machine,” the depiction of a made-up archeological site, evincing too much red pigment for my taste, took 10 years and was never finished, or only “finished” when it was purchased by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and thus left his studio.]

Masterpieces Gone Missing

At Babcock, the closest thing to one of the “winter paintings” is Francis Foley (1927), only 50 by 40 inches, but exhibiting the silvery tonalities and skewed perspectives of the big works. And the fabric. A must-see. And the first-strike paintings are also worth braving jolly Christmasy midtown Manhattan. Self-Portrait in Uniform of 1942 (it’s a Civil War getup) is also special, self-portraits being his third specialty, developed in the second half of his life. They too are destabilized. Are they vain or introspective?

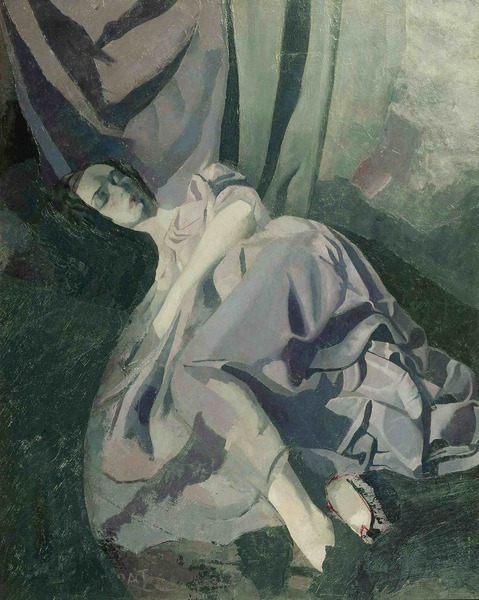

In the survey now at the Brooklyn Museum called “Youth and Beauty: Art of the American Twenties” (to Jan. 29), you can see Dickinson’s Helen Souza, 1929, which, although hardly one of his “big ones,” is twilight gray, utilizes a surprising perspective and point of view, and is a startling exercise in surface, texture, and varied paint-application. Is it unfinished? What is the struggle that it embodies? Plastic or psychological, or both?

Alas, neither MoMA, the Whitney, nor the Metropolitan have any of their once very popular Dickinson“subject paintings” on display right now. They are — dreaded term — in storage.

He Was Not a Hermit

Whatever happened to Dickinson? Although he eventually moved to New York, he is associated with Provincetown, Massachusetts. Too New England. Furthermore, in the battle between Provincetown and Woodstock to become the summer art capital, East Hamptonwon. Dickinson lived in P-town and later in nearby Wellfleet year-round. However, let us not think Dickinson was unsociable because he spent 14 bone-chilling Cape Cod winters in uninsulated studios making art.

From his spare diaries we learn how disciplined he was. Up early, out on the beach, then scraping paint in whatever draughty workspace he could afford. But he also keeps track of a full social life.

Still feeling ill – up late painted myself AM.. PM painted eve home…..AM painted – PM painted. Eve saw Manon. Rec’d valentine scarf from Tibi. Bright moonlight on snow. Cold…AM in & out – walk on dunes. Wretched day. PM worked at office. eve at Tibi’s.

The early death of his long-suffering mother from tuberculosis and the suicide of his older brother were anniversaries dutifully noted each year in the pages of his day book, with never a comment. Just there, like winter, like ice.

His definition of art was “something that moves the spirit through the eye.”

When asked about his influences, he replied: “I suppose being alive and awake.”

When queried about the meaning of his art, he replied: “I wouldn’t be able to say.”

Dickinsonwas the last of the art line that goes from the Munich School to William Morris Hunt, William Merritt Chase and Charles Hawthorne. Dickinson studied with both Chase and Hawthorne, the latter when he had an art school in Provincetown.

In many ways, he was also one of the last of the independent artists.

He was accustomed to the largesse of juried exhibitions and exposed his art that way, as did many others before the advent of the full-fledged gallery system. For long stretches he was ‘”commercially unaffiliated” and seemed not to have minded. Although he had shown at the then prestigious Carnegie Institute, the Albright-Knox, and the American Academy of Art., his first solo exhibition in a commercial art gallery was in 1936 on 57th Street in New York at the young age of 45.

After 1942, he went without a gallery until 1961. Of course, he was nicely represented in curator Dorothy Miller’s MoMA show “Romantic Painting in America” in 1942 and again in her “15 Americans” of 1952 (along with Rothko, Still, Pollock, and Bradley Walker Tomlin). When asked to submit an artist’s statement, he submitted a self-portrait.

Elaine de Kooning’s “Edwin Dickinson Paints a Picture” (Ruin at Daphne) appeared in Art News in 1949. She wrote that he was “A great artist [who] reconciles poetry with perspective.”

He was not invisible.

Otherwise, he saw nothing wrong in teaching. From various accounts, his students at Cooper Union and the Art Students League were in awe of him, but appreciated that his critiques were strictly one-on-one. He treated students as if they were fellow artists. Here’s an interview with painter George Nick, a former student.

But perhaps he should have stayed in Provincetown or Wellfleet and froze to death. Perhaps he should have walked out to the tip of the Cape Cod curl and just waded into the icy brine to join his beloved brother in the afterlife, leaving behind his wife and two children to go it alone. His brother in the ‘20s had leapt from a sixth-floor window in Greenwich Village, almost in front of his eyes.

When economic necessity forced Dickinson and family to move to New York City, where there were more teaching jobs, he clearly did not have the time or energy to paint more of his large paintings. Francis V. O’Connor, in the big Buffalo tome mentioned above, offers more than enough intuitive psychoanalysis in his essay, “Allegories of Pathos and Perspective in the Symbolical Paintings and Self-Portraits of Edwin Dickinson.” Once Dickinson was safely married, his oedipal conflicts were resolved. His father could be forgiven at last for marrying so soon after the first Mrs. Dickinson’s death. Of course, no more “winter paintings” were in the offing.

- Dickinson, Ruin at Daphne, 1943-53. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Not on view.

An Unfinished Life

The story of Dickenson’s life has not much to it; but his art does. Sometimes the large paintings were cut down into smaller paintings. Sometimes just abandoned. He told arts writer Katherine Kuh:

None of the large paintings is really finished. there comes a time when I stop because to go on would mean reorganizing the canvas from the bottom up. I can’t throw away the investment of so many years — nine years in the case of Ruin at Daphne. So I make the best of a bad job by finishing them as well as I can. In other words, they all topple over when they are about three-fifths done.

So like Willem de Kooning!

In fact he and de Kooning, 13 years his junior, became friends. Dickinson, the elegantly bearded art teacher, valorized spontaneity and indecision or struggle, which may have influenced the younger man. Certainly, as Elaine de Kooning (who introduced them) might have predicted, there was a resonance between the two.

Oh, to see some paintings by each side-by-side!

What Goes Around Comes Around

Why are Dickinson’s six big paintings so spatially and emotionally unsettling? Is it because they simply do not fit any known style-category?

I hypothesize that their previous popularity can be accounted for not because they seemed antimodernist, but because they are doom-ridden, anxious, nerve-wracking. There is always a market for doom. You can stand only so much Matisse.

Antimodernism we can deal with. It is just the other side of the coin. But Dickinson’s upsetting machines stand clear of the game. They are not morbid like the rotting figures of Ivan Albright. They are wreckage, if not debris. The viewer is flummoxed, puzzled, fascinated, transfixed, like the South Pacific trading partners of the Trobriand who were paralyzed by the ornately carved canoe prows they confronted. No normal man could have made these complicated paintings. (Yes, I have finally gotten around to reading Alfred Gell’s witty, insightful, game-changing Art and Agency, An Anthropological Theory.)

In the recent Dickinson literature, romantic hopes abound. He will be the new Ryder or the new Hopper, rediscovered in the nick of time and saved from unjust oblivion by an unforeseen bend in art history. Have we come to that bend?

Can’t happen. Won’t make a good enough story.

Throughout his life, Dickinson loved going to the movies, beginning with the silents. Perhaps they influenced his machines and even his first strikes: tilted points of view, views from above, truncated subjects. But picture a film in which we see exact, real-time recreations of Dickinson painting, scraping down and repainting his machines indoors, the artist wrapped in coats and scarves; then intercut with the spontaneous, outdoor first strikes; then reels of him teaching class after class at Cooper Union, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Art Students League until, with the exception of the self-portraits and a few first strikes, the teaching takes over the art-making.

“One learns to draw faces better by painting torsos,” he tells a class.

“Love,” he tells a stymied student, “will find an answer.”

Or, my favorite, “Taste is the enemy of art.”

And then there is the total strangeness of his most famous painting, The Fossil Hunters, which took 192 sittings. It was mistakenly exhibited sideways, not once but twice. Is this because he signed it vertically on the right side? The first time was at the 1928 Carnegie International. Corrected for an exhibition at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, it was then shown sideways again and stayed that way at the National Academy of Design in New York, where it won the Altman Prize for Landscape. That would be the center of my allegorical biopic.

Advice for Young Artists

1. Don’t get married and have children.

2. Don’t teach.

3. Don’t make more than one kind of art.

4. Make lots and lots of product. Picasso made 40,000 artworks; Warhol clocks in

at 10,000, not counting prints (in some sense they are all prints). Damien

Hirst, who has so far made only 4,800 works, not counting prints, was quoted

by the L.A. Times as determined to beat the both of them.

5. Always be able to explain what you are doing.

6. Always sign your artworks at the bottom, front or back; and indicate the top on

the back. Never, never sign vertically down the side. That’s just asking for

trouble.

7. Eschew tactility, varied surfaces, paint-handling.

8. Produce artworks that are photogenic.

9. Never be ahead of the curve.

10. Don’t be too original; just be original enough to make your product a brand.

Too much originality is always punished or ignored.

_______________________________________________________________

Fast Track:

***** An Edwin Dickinson Retrospect, Babcock Gallery

**** Late Works of Matta, Pace Gallery

*** Diego Rivera Murals, MoMA

** Francis Picabia, Michael Werner Gallery

* Youth and Beauty: Art of the American Twenties, Brooklyn Museum

To sample John Perreault’s sand paintings you may preview online the Kauai Museum catalog for Mark Van Wagner and John Perreault: Drawing from Sand, with a short essay by art critic Peter Frank. Click Here. The exhibition runs from Nov. 12 to Jan. 20 in Lihue, HI. then travels to the Lincoln Gallery, Naropa University, Boulder, CO., opening March 16.

For easy access to 200 previous Artopia essays by topics, go to top bar, click on ABOUT, click on ARCHIVE, then scroll down to listing by Headlines.

NEVER MISS AN ARTOPIA ESSAY AGAIN! FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT contact perreault@aol.com

John Perreault is on Facebook. You can also follow John Perreault on Twitter: johnperreault

For Art Cops cartoons and other videos on Youtube: John Perreault Channel. Main John Perreault website. More of John Perreault’s art.