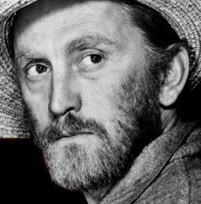

John Perreault as van Gogh in Les Levine's Analyse Lovers, The Story of Vincent, 1990. Still from video.

A new biography, Van Gogh: The Life, by Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith, suggests Vincent did not commit suicide, but was shot by a perky local of 16 named René Secrétan, who was wearing a cowboy costume.

The bullet’s trajectory showed the shot could not have been self-inflicted and had to have been fired from afar.

But if this is true, why did Vincent protect his assassin? The bully had been tormenting him for months by putting salt in his coffee and setting up fake dates with farm girls. You would have thought he would want some revenge.

Vincent was a Christian. Thus forgiveness should have been part of his character. Maybe that explains it. Or, and this is now the preferred interpretation, he committed suicide-by-hooligan, the way those too afraid to off themselves sometimes taunt the police into doing the job.

I have a better theory. Vincent had been having his way with René; and the lad, clearly not the brightest bulb, decided to defend his honor. From afar. The cowboy suit made me suspicious from the beginning. Even in the 19th century a cowboy costume on a 16 year-old was not the mark of maturity. He should have been knocking up farmers’ daughters or planting potatoes, not playing cowboys and Indians or whatever he was doing. Maybe he was dressing up for the artist.

Michiko Kakutani, in her N.Y. Times Book Review, is on the suicide side:

The deeply unhappy van Gogh, the authors argue not altogether convincingly, “welcomed death,” and Secrétan may have provided him “the escape that he longed for but was unable or unwilling to bring upon himself, after a lifetime spent disavowing suicide as ‘moral cowardice.’”……. There is no hard evidence for this theory, and it is laid out, discreetly, in an appendix to this biography.

On 60 Minutes, one of the biographers, Gregory White, is at least more forthcoming about the murder:

.

Yet the segment ends with a quote from an unidentified BBC art critic. He claims the van Gogh death-bed statement was: “Do not accuse anyone, it was I who wanted to kill myself.”

Why the cover-up? A martyr is a martyr, right? What difference does it make if Vincent was killed by culture-clash, class-conflict, hatred of art or by his own hand?

Media cannot bear corrections or ambiguity. Myths are not allowed to be changed. It would be too destabilizing. We can no more change the van Gogh ending than we can change Little Red Riding Hood.

Are museums immune? No. There’s also a wait-and-see statement from the Van Gogh Museum, quoted in the above broadcast. The museum’s curator Leo Jansen told Dutch News “the findings are not sufficiently supported by the facts…The interpretation is interesting but there are still a lot of unanswered questions. The museum thinks it is too early to change the cause of death from suicide.”

Are they afraid that if it becomes generally known that Vincent did not put the gun to himself, it will effect their gate?

In print, even the biographers who amassed the anti-suicide evidence hedge their bets. Vincent was depressed. So what else is new? He felt guilty that Theo, his art-dealer brother — who had been supporting him — had not been able to sell one paltry painting. He wanted to die. Wait a minute. Shouldn’t Theo have been the one that felt guilty about not selling any paintings? Oh, I forgot; art dealers never feel guilty.

The real issue is not whether or not Van Gogh killed himself but why there’s the need to cling to the suicide myth. Theo, who rushed to Vincent’s bedside, seems not to have investigated, even though the locals thought their rowdy René did the dirty deed. If you were Vincent’s brother wouldn’t you have wanted to seek justice?

Not if you were his brother and his art dealer.

Another art dealer, Amboise Vollard, a few years later, apparently advised Paul Gauguin, Vincent’s old buddy, to stay put in the South Seas although he inexplicably longed for Paris. We know from recent excavations of Gauguin’s well that at the end, the artist was drinking a lot of bottled beer from New Zealand and shooting up with morphine. If he returned to France he was told his paintings wouldn’t sell.

Theo van Gogh died of syphilis six months after his beloved brother Vincent passed away from a festering bullet. Theo’s widow then made a fortune off of Vincent’s paintings. The suicide story worked.

I once channeled Vincent in artist Les Levine’s Analyse Lovers: The Story of Vincent, for Dutch National Television (commissioned for the 100th anniversary of van Gogh’s death). Levine thought I looked like van Gogh, a fatal mistake. At the press preview, the reporters only wanted to know where he had found such a talented actor to play Vincent.

On camera, I went into a kind of trance. I revealed the truth about cutting off my ear for Gauguin. But the end game, the shot to the chest, was never part of the video. Yes, chest. Not head. I bet you have always imagined a shot to the head, perhaps to the temple. But that self-portrait I did with the bandage was years before, when I cut my ear.

Now I can reveal, speaking through John Perreault, that I lied on my deathbed — not to shield the naughty culprit, but to incite posthumous sales and please my brother.

Myth is all. Suicide makes a better sales point than death-by-yokel.

Why We Need Myth

Own up to it. Aren’t we disappointed that the laboriously decoded Maya hieroglyphs reveal nothing more than when to plant maize and the succession of Mayan despots? We already knew the Mayans had independently invented the concept of zero. That should have been enough. But we have secretly been hoping that they had predicted the end of the world. We adore apocalypse.

And, confess, you felt let down when you read that Vincent didn’t kill himself. Too messy.

We need closure. We need the myth of the crazy, tormented, self-destructive artist to convince us that painters, poets, and musicians are all nuts, so their larger-than-life lives can continue to offer escapism from the bourgeois armchair of our own lack of freedom. And also, paradoxically, make us feel relieved we are not artists. In our dreams, van Gogh must commit suicide, otherwise the story doesn’t have legs.

______________________________________________________________________________________

To sample John Perreault’s sand paintings you may preview online the Kauai Museum catalog for Mark Van Wagner and John Perreault: Drawing from Sand, with a short essay by art critic Peter Frank. Click Here. The exhibition runs from Nov. 12 to Jan. 20, in Lihue, HI.

For easy access to 200 previous Artopia essays by topics, go to top bar, click on ABOUT, click on ARCHIVE, then scroll down to listing by Headlines.

NEVER MISS AN ARTOPIA ESSAY AGAIN! FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT contact perreault@aol.com

John Perreault is on Facebook. You can also follow John Perreault on Twitter: johnperreault

For Art Cops cartoons and other videos on Youtube: John Perreault Channel. Main John Perreault website.

More of John Perreault’s art.