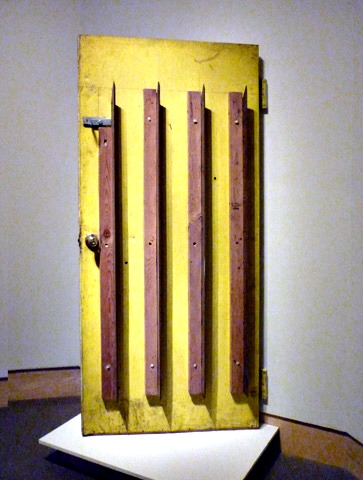

George Maciunas, Giant Cutting Blades Door from Flux Combat with New York State Attorney (and Police), 1970-75

Fluxus is in flux. The interpretations are coming fast and furious. The latest entry is the imaginatively titled exhibition “Fluxus and the Essential Questions of Life,” with works mainly selected from the George Maciunas Memorial Collection at the Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, but with significant additions from MoMA and other sources. It is now at NYU’s Grey Art Gallery until December 3.

In her essay, curator Jacquelynn Bass writes:

The point is to experience Fluxus artworks for yourself. These days that will most likely be from behind Plexiglas or two-dimensionally, as in the pages of this book. Since all experience takes place in the mind anyway, that is probably all right. The section introductions … are offered as optional assists for the viewer/reader.

As if to prove her point that Fluxus addresses rather deep themes in spite of the whimsy and the flimsy and the flim-flam, the entertainment value and the wit, Bass divides the work into 14 categories. To provide a quick tour of the exhibition, here they are (with my comments added):

Art (What’s It Good For?) How does Robert Filliou’s Ample Food for Stupid Thought (e.g., the words: “Why Did You Do That?” ) relate to the purpose of art? There’s a great deal of nose-thumbing in this show, as to be expected.

Change? Everything is change, but why is Mico Shiomi’s Water Music ( a bottle with eye-dropper and label: “1. Give the water still form; 2. Let the water lose its still form” classified under Change rather than Time? Same for Yoko Ono’s Flux Film #4 (lighting a match); it could be under Danger or Time.

Danger? Fluxus magus-wannabe George Maciunas’ Giant Cutting Blades Door from Flux Combat With New York State Attorney (and Police), 1970-75, certainly looks dangerous. It’s one of the best pieces in the exhibition and a big and very weird surprise. Dangerous? Not really. It was only dangerous to cops, or anyone trying to break down the door. What was the dispute? Illegal occupancy? Maciunas was notorious for challenging NYC building regulations, buying lofts in Lower Manhattan and selling them as artist co-ops. And so SoHo, as we now know it, was born and rapidly became a haven for jet-setters. The rich want to be where the artists are, but to do that they have to drive the artists out. Maciunas’ Door (from his own loft) is a Fluxus masterpiece — in itself, a neat contradiction of terms. But it could have been filed under Paranoia or Real Estate, categories that are not on the curator’s list.

Death? Most items here are on topic, but of course they offer no solutions to this essential question. Two examples: Ben Vautier’s A Flux Suicide Kit, 1963; George Brecht’s one-word Exit (1962-3). The latter has always been a favorite of mine, reminding me of Barnum’s famous sign, posted in his Lower Manhattan museum of wonders, geeks, freaks, and fabrications: This Way to the Egress. Or maybe something deeper?

Freedom? This category seems to be about offering the viewer choices, but that is not the case with Geoffrey Hendricks’ wonderful Sky Laundry (1966-72) — painted clouds on a blue-sky sheet, hung up to dry. It would be a better fit in a nonexistent category we could call Poetry, if that would not confuse everyone. Fluxus poetry is usually thought to overlap Concrete Poetry and Sound Poems.

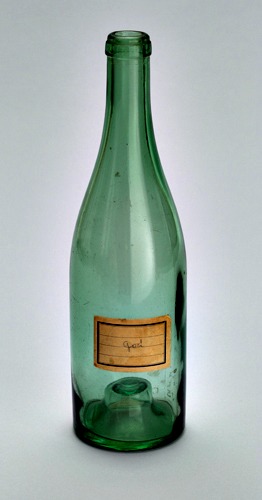

God? Ben Vautier’s bottle with the word God penciled on it yields these questions: Is wine the drunkard’s god? Is wine the blood of you-know-who?

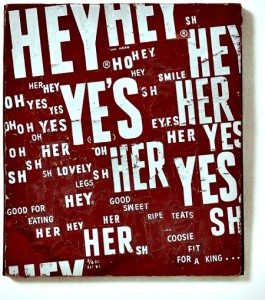

Happiness? Anything Fluxian that provokes a smile, or pictures a smile, or has the word smile in the title — like Yoko Ono’s Box of Smile (spoiler: a small box with a mirror in it) — is supposed to be about happiness. I say cheesecake. I say let a smile be your umbrella.

Health? I cannot associate Maciunas’ Fluxsyringe (1973), made of 56 hypodermic needles, with health. I see needles and think heroin.

Love? Love is not one of the essential questions of life, nor is it one of the answers. Sorry to disillusion you. Love, as we all know from French movies in the ‘60s, is trouble.

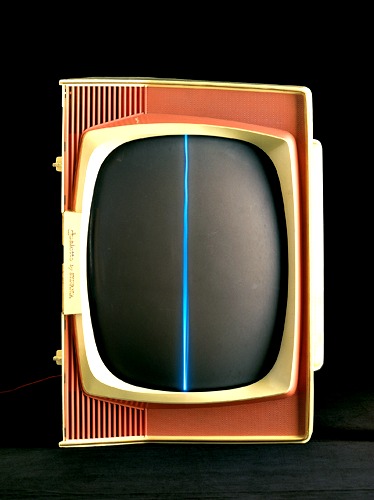

Nothingness? Nam June Paik’s Zen Film, 1965 — 20 minutes of 16mm film-leader — is a good try at nothingness. But a film is something, isn’t it? When you run a blank film through a projector it accumulates scratches. You cannot picture nothingness; you cannot hear it or see it. You can only be it.

Sex? To put Yoko Ono’s Cut under this category is offensive. Or sadistic.

Staying Alive? Here the artworks are mostly food or food-related. But we do not live by food alone.

Time? Robert Watt’s excellent 10 Hour Flux Clock, 1969 (a clock altered to show only 10 hours, is about clocks, not time. This and other pieces fail to really, really question time. After all, what do clocks have to do with time?

What Am I? Well, in spite of Robert Watts’ Fingerprint, we are not our fingerprints. Identity is not identification.

The Fluxus Fungus

Perhaps I quibble. Couldn’t these categories, like Fluxus itself, be even more arbitrary?

Almost anything could fit in any category.

In the spirit of Fluxus, we propose other categories that will serve just as well to get you through the heterogeneous material without having to worry too much about what Fluxus is or is not. My definition is that any work or artist called Fluxus is Fluxus, even if the work in question is really a Happening (i.e., not monologic) or if the artist didn’t get along with kingpin Maciunas (Al Hansen).

My definition is that Fluxus is a kind of fungus. My definition of Fluxus is that it is John Cage’s unintended curse. My definition of Fluxus is that it is whatever you have left when you take the spirituality out of Zen Buddhism.

Instruction: Reclassify the games, toys, films, sculpture, performance and/or event instructions in the exhibition according to these categories I now propose. These are my Essential Questions of Life.

Science? George Brecht, Three Aqueous Events, 1963…”ice, water, steam.”

Communication? Maciunas, Aging Men Fluxpost, n.d. Sheet of postage stamps picturing aging men.

Cruelty? Geoffrey Hendricks, 2 aRt Traps, 1978. Mouse trap with captured paint tube.

The Industrial Medical (Musical) Complex? Alison Knowles, Wounded Furniture, 1965. “this piece uses an old piece of furniture in bad shape. Destroy it further, if you like. Bandage it up with gauze and adhesive. Spray red paint on the wounded joints. Effective lighting helps….”

Hunger? Robert Watts, Yam Ride, c.1962. YAM RIDE stenciled on a Goodyear tire.

Paranoia? See comment above under Danger.

Real Estate? Ditto.

Plus these:

Downtime? Language? Pollution? Fog? Translation? Transportation? The Sexual Transmission of Acquired Characteristics?

Couldn’t we do away with categories and use simple systems instead, such as:

Alphabetically by title.

Or by size.

Or weight.

Or chromologically. Because there is not much color here — mostly words, toys, and little boxes – color, it could be argued, is enormously important.

Someone I know was in his youth engaged as the sole clerk in a bookshop somewhere in Southern California. Hardly any customers, because in that neck of the woods, where there were several very large universities, no one read – even then. So he passed his time by arranging the books chromologically.

Is This The End of Fluxus?

No, this is not the big Fluxus museum show, demanded this year by the Artopia Art Cops, the show that will finally end all Fluxus forays. I myself would gladly settle for an in-depth survey of events, films and videos, instruction pieces, and the big stuff, leaving out the toys.

I hate toys.

Plus, as the name implies, Fluxus keeps changing. Is it still alive? Is it mischief “made mechanical”? Is it, as Pope Maciunas said, “gags” rather than art? Why can’t it be pinned down? Is there Fluxus Redux or Neo-Fluxus? Is there Fluxus DeLuxe?

One good thing about Bass’ exhibition is that Ray Johnson has been omitted. But where is Lil Picard or James Lee Byars or Joseph Beuys?

There must, alas, always be a compromise between the comprehensive and the comprehensible. You have to draw a line somewhere.

Worthwhile also is MoMA’s “Things/Thought: Fluxus Editions – 1962-78” (to January 16). It is so deftly selected, so beautifully displayed, you might even come away convinced that Fluxus editions were art of some sort. After all — although you would not have a clue here — this was also the time of 3-D prints or multiples “created” by Pop artists and their kin. But most Fluxus items, I am told, unnumbered and graphic designer Maciunas never made a cent on any of the little boxes, books, and other ephemera he produced for mail-order and the year-long Fluxshop on Canal Street. Were Fluxus editions parodies or predecessors of fine-art multiples?

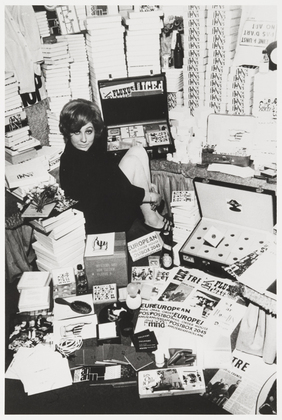

Here we get to see the European Mail-Order Warehouse/Fluxshop crammed with stacks and piles of Fluxstuff, but outside the box we may peruse neatly displayed films, kits, cards, newspapers, posters, and other Fluxiana by Fluxters from Brecht to Watts.

Complementary to “Fluxus and the Essential Questions of Life” is “Fluxus at NYU: Before and Beyond,” jammed in downstairs at the Grey Art Gallery. This is all from the Fales Collection at the NYU Library and the NYU art collection. You should see this first and not worry too much that Jackson Pollock, Robert Rauschenberg, and Yvonne Rainer (for instance) cannot really be considered part of Fluxus. What their presence provides is a indication of a gestalt, a kind of map of what was surrounding Fluxus … and in a few years subsuming it. Now we are collectively exhuming Fluxus because we again seem to need art that at least pretends to be anti-commercial, anti-object, anti-establishment, anti-pompous. And dare I say it? Art that is not a marketing strategy.

Fluxus has been re-materialized at last, like a ghost at a seance. But, if you will pardon the mixed metaphor, is this the only way to nail down its place in art history? Does an artist-approved, latter-day manifestations of Yoko Ono’s 1960 Painting to Be Stepped On (at Grey Gallery) still question authorship and what I call the categorical imperative? I experienced Painting to Be Stepped On, at first not even knowing I had stepped on a painting, in 1960 at her downtown loft. You had to step on an all-white canvas on your way in to a LaMonte Young “concert” that, as I remember it, involved the composer, assisted by Walter de Maria, making a straight line with a string from one end of the space to the other. Can you step on a painting twice, particularly when the new painting, stepped on consciously and with perhaps too much glee, is a sacrificial offering from an artist on the NYU faculty?

———————————————————————————————————————————–

For easy access to 200 previous Artopia essays by topics, go to top bar, click on ABOUT, click on ARCHIVE, then scroll down to listing by Headlines.

NEVER MISS AN ARTOPIA ESSAY AGAIN! FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT contact perreault@aol.com

John Perreault is on Facebook. You can also follow John Perreault on Twitter: johnperreault

For Art Cops cartoons and other videos on Youtube: John Perreault Channel. Main John Perreault website. John Perreault’s art.