Willem de Kooning’s difficult masterpieces, recently so unfashionable, can now be seen with new eyes. De Kooning’s work for decades was virtually blacklisted by Greenbergian formalists, but MoMA makes amends with a well-chosen and complex survey. “Willem de Kooning, A Retrospective” at MoMA to January 9 is the must-see of the fall season. Jackson Pollock was great, but so was de Kooning, and we are here reminded why.

Of course, the single minded cannot allow anything but a single line. Art-historical descent does not allow dissent, or anything beyond clear-cut teleology. De Kooning’s error is that he seemed not to have left behind descendants who needed justification by patrimony to boost their prices, whereas Pollock supposedly fathered Helen Frankenthaler, Jules Olitski, and maybe, just maybe, Kenneth Noland. We need a new schemata.

Last season’s MoMA survey of Abstract Expressionism was not good enough to bend the curve. The MoMA de Kooning show might.

Anger, angst, and ambiguity can no longer be repressed. De Kooning descended from Picasso; Pollock from Thomas Hart Benton.

Certainly we have had splatter, scatter, and sputter art, but it has been art about splatter, scatter, and sputter without emotions or struggle. It has been Abstract Expressionism without the expression. It has been Anti-Form Post-Minimalism.

Time Is Not a Series of Boxes

De Kooning outlasted Pollock and so there are distinct periods as identifiable as Picasso’s. For starters, MoMA lists:

Men, Women and Interiors, 1938-1945

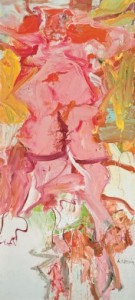

Pink Angels to Black and Whites, 1946-1948

Around Excavations 48-50

Women To Landscapes 1950-56……..

The above link will bring you to the “Periods” section of MoMA’s ambitious online educational exposition of the retrospective exhibition, complete with images….

Squeezing de Kooning’s work into “periods” results in a certain awkwardness, to say the least. These periods (i.e., “Pink Angels to Black and Whites, 1946-48” or “Women to Landcapes, 1950-56”) refer to a few years at a time and not to stylistic periods (i.e., Picasso’s Blue Period or de Chirico’s Neo-Impressionist Period). As far as I can see, de Kooning did not focus on one idea or stylistic set and then move on to another distinct constellation of attributes.

Very inconvenient.

On the other hand, unlike his peers Newman, Reinhardt, Rothko, and Still, he did not fasten upon a signature style. He probably could have gone on making grimacing women for the rest of his life. But — this critic maintains – his touch, his hand, his manipulation of surface and color, his complex interplay of figure and ground make up his signature. The means were the ends.

To get closer to the way de Kooning actually worked MoMA’s enumeration and illustration of Themes LINK is the more helpful deposition:

Over the course of his long career, Willem de Kooning continually shifted his painting style, using innovative techniques and always searching for a different means of expression. Several themes, such as the female figure, permeated his work along the way. This section of the website allows viewers to see the artist’s works thematically rather than chronologically, highlighting the extremely varied approach to a particular theme or subject matter at different points in his career.

Thus we are confronted with an unidentified, Artopian braid. Say it: braid. There’s a strand for each theme as it weaves in and out of other themes. Suddenly the variety makes sense. That no one at the time was painting this way makes it all the more important to clarify the de Kooning braid. In his own practice he was objectifying the way art works historically.

Of course, critic Harold Rosenberg (who saw what his rival Clement Greenberg did not want to see) was right. The paintings are about action, struggle, process more than form. De Kooning ate ambiguity for breakfast. And doubt.

Jackson Pollock in his best work showed no signs of doubt. Newman, Still, and Rothko made doubt heroic or single-minded. Or simple-minded? De Kooning made doubt part and parcel of everyday life.

To doubt is to live.

Is this painting finished? He mixed up great messes of salad oil and pigment so the paint wouldn’t dry. An emulsion compulsion. He did not finish paintings; he abandoned them. Even in his endgame, the paintings were taken away from him, rather than concluded. Bossy Elaine de Kooning (now back on board since 1975) and one hired hand or another would point out empty areas on the canvas they thought he had forgotten. He was urged to go beyond his now favored red, yellow, and blue on a white ground and even whipped up some ghastly greens and purples for him.

Is this painting resolved? Is life resolved?

De Kooning is what I call an oil-and-water artist. He refuses to give up either figuration or abstraction, happiness or fear.

And then there is the constant unfolding of what’s there. Or not there.

- De Kooning, Woman I, 1950-52

The Goddess Is Not Modest

The Women had to do with the female painted through all the ages, all those idols, and maybe I was stuck to a certain extent. I couldn’t go on. It did one thing for me; it eliminated composition, arrangements, relationships, lighy — all this silly talk aout line, color and form — because that is the thing I wanted to get a hold of.

I wasn’t concerned to get a particular kind of feeling. I look at them now and they seem vociferous and ferocious. I think it had to do with the idea of the idol, the oracle, and above all the hilariousness of it.

Willem de Koonng: Collected Writings, Hanuman Books, 1988.

Woman-hater? No, he loved them perhaps too much. His biography is replete with love mistakes. We have been taught to think, misguidedly, that his notorious and career-making “Women” paintings represent contempt. Sorry. They are fear and comedy. He himself once said they were inspired by his wife Elaine:

“I had a quiet profile. I used to paint quiet paintings,” he told interviewer ¬Edvard Lieber. “Before I met Elaine I painted quiet men. Then I started to paint wild women” (Willem de Kooning: Reflections in the Studio, Abrams, 2000, p.129¬).

After reading De Kooning, An American Master by Mark Stevens and Analyn Swan (Knopf, 2004) you might easily conclude that Elaine Fried de Kooning was a hard-drinking, self-centered monster. In Artopia we never thought much of her as a painter. And she could never be compared to her husband, before or after their long separation. She did an official portrait of Jack Kennedy; he painted Marilyn Monroe, parkways, clam diggers, and freedom.

Harsh words?

Read the Stevens and Swan biography and you will wonder why de Kooning was so wimpy when it came to women. Passive aggressive? Too busy painting? And then we learn that in spite of his reputations for conviviality and brawling, he was pretty much a loner. Away from New York, he lost touch with his old neighbors — dance critic Edwin Denby and photographer Rudy Burckardt — and New York School poet friends. Battling binge-drinking and failing, stuck with only a bike in lonely Long Island, minded sometimes by assistants who were too often drunks themselves…age crept up.

Fortunately, he was more right-brained than left-brained. He thought with his bright blue eyes, his hands, his arms, his whole body.

But just remember this: in spite of his hard drinking, chain-smoking, and Alzheimer’s, he outlasted most of his competitors! Including Elaine Fried de Kooning — who had come back to claim her share of the proceeds of his life in art. At one point, he thought she was trying to take away his house and studio.

Nevertheless, she kept him painting in the ’80s on the theory it was helping him stay alive. And to make sure there was an estate to inherit? Who knows. The assistants sometimes made drawings on bare canvas based on previous paintings to start him off. There was even a contraption to rotate the paintings so he could determine which end was up.

If this were a movie no one would believe that the long-gone wife would suddenly return when hubby, who somehow neglected to divorce her, still had a market, still was painting, but was mentally in bad shape.

As it turned out, Elaine died first in 1989, leaving behind, we are told by biographers Stevens and Swan, a collection of high-end shoes so large that it had to be curated, a stash of expensive jewelry, and the love of her relatives who had received gifts of Bill’s paintings. When de Kooning died in 1997, his daughter (by Joan Ward) inherited all the estate, not just half, which would have been the case if Elaine had survived her old flame Bill. (He was one of many old flames, including Milton Resnick and critics Rosenberg and Thomas Hess.)

The beloved daughter, one supposes, selected music of Alan Hovhaness and the triumphal march from Aida for de Kooning’s East Hampton funeral, not what he had wanted, which was Frank Sinatra singing “Saturday Night Is the Loneliest Night of the Week.”

The Test

Recently I was sickened by the ill-conceived “Real/Surreal” selection from the Whitney collection. Except for great but out-of-place paintings by Sheeler, Hopper and Hartley, it reminded me why Abstract Expressionism was necessary. Then I thought to myself, because I remember liking some of these very same paintings when I was a kid, that maybe I am just in a bad mood. After all, I didn’t like the Ree Morton wallpiece upstairs, and I used to like her work, too.

Fortunately, there was a test. Off to the side, but also on the second floor, was a de Kooning unrelated to “Real/Surreal” and all by itself in a kind of alcove (shrine?). One of the parkway landscapes. It was glorious. So, no, it wasn’t my mood — which, though I possess an inexplicably sunny disposition, can effect the way I see art. It was the art in “Real/Surreal.” More Magic Realism then true Surrealism. Ghastly stuff.

I didn’t particularly like the Whitney’s “David Smith: Cubes and Anarchy,” either. An academic corrective to the notion that this formalist-favored sculptor came to rectangles only in his late Cubi series does not disguise that even in his last, supposedly greatest, period he was still chained to the figure. All the sculptures have fronts and backs. They are cutouts or silhouettes, therefore hardly sculptures at all. The man couldn’t think in three dimensions, never mind that he owed everything to Picasso. How’s that for revisionism? And it wasn’t my mood. I went back upstairs to the fifth floor. The Robert Morris Minimalist sculpture looked great.

De Kooning Did Not Repeat Himself, Nor Should I

Is there anything new to be said about de Kooning? We don’t want to go through the same old shrink-wrapped palaver. Surely there is something deeper in de Kooning than his worship of and rage at the White Goddess, as she was once called when all the rage. No one even remembers that terrible British poet Robert Graves, who uncovered her grave. To old-type feminists, I would suggest that men are not the only ones who hate their mothers. Mother-daughter conflicts are just as bad as father-son ones. Can’t we look at de Kooning’s women in the same way we look at that other post-war phenomenon, the bigger-then-life big, bad dames of film noir? To know them is to love them.

And we don’t want to repeat the stories told over and over about de Kooning in his cups, throwing Franz Kline through the front window of the Cedar Bar. Kline probably deserved it.

Is de Kooning’s greatness confirmed? Has it even begun to be parsed? Like the founding “dear leader” of authoritarian North Korea, de Kooning also had the required “three greatnesses.”

Here I should confess I have been watching a number of Netflix streaming documentaries about North Korea and one hilarious mockumentary (Jim Finn’s avant-garde The Juche Idea). The Danish The Red Chapel is hilarious and awfully sad, too. Daniel Gordon’s Crossing the Line, about an American deserting to North Korea, is mind-blowing.

In the meantime, please memorize:

1. Leadership. Many tried to follow in de Kooning’s footsteps, but most of the second-generation Action Painters were a sorry lot. He led them over a cliff. His true successors (open for revision) were Robert Rauschenberg, who erased a de Kooning, Alan Kaprow, John Chamberlain, Alice Neel, Joan Mitchell and Joan Snyder.

As someone once said: Not all of my children need to look the same, nor should they.

2. Ideology. Art is the only thing worth doing; art is the only life worth living.

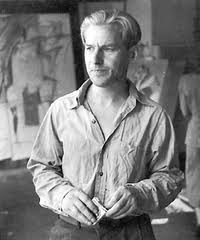

3. Aura. Even as an old man he had drop-dead good looks. But aura isn’t just looks, it’s being at center-stage no matter where you are. Aura is the spotlight that never dies. The follow-light that always follows. The silence that gets attention. Most important, his aura was mysteriously embodied in his paintings, in the gestures, the enjambment, the wreckage of Cubism.

___________________________________________________________

For easy access to 200 previous Artopia essays by topics, go to top bar, click on ABOUT, click on ARCHIVE, then scroll down to listing by Headlines.

NEVER MISS AN ARTOPIA ESSAY AGAIN! FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT contact perreault@aol.com

John Perreault is on Facebook. You can also follow John Perreault on Twitter: johnperreault

For Art Cops cartoons and other videos on Youtube: John Perreault Channel. Main John Perreault website. John Perreault’s art.

- Share this: