Would You Believe This If It Were Science Fiction?

Over the course of a century, Aussie cops and “Aboriginal Protection Officers” kidnapped some 100,000 “half-caste” indigenous Australian children from their mothers. Many of the youngsters had been sired by white, ex-convict, railroad workers and other Anglo-Australians who also built and maintained the coast-to-coast rabbit fence. Yes, the State Barrier Fence, first called Rabbit-Proof Fence No.1, was built from 1901 to 1907, running north to south, from shore to shore, across Western Australia to keep rabbits and kangaroos from eating the crops. At one point, maintenance inspectors used bicycles to patrol the world’s longest fence. The North-South “Ghan” railway was begun in 1878.

The kidnappings, believe it or not, were to “protect” the dark-skinned, sometimes blue-eyed children by handing them over to Methodist-run schools or settlements where they were taught how to be farmhands and domestics. They were forbidden to use their own language(s) and to practice their own religion; marriage with whites was urged. The barely concealed strategy was that by the third intermarriage there would be no “blackness” left. In short, by assimilation through “education” and intermarriage the indigenous race would disappear, affirming the supremacy of their white saviors and the God of mercy.

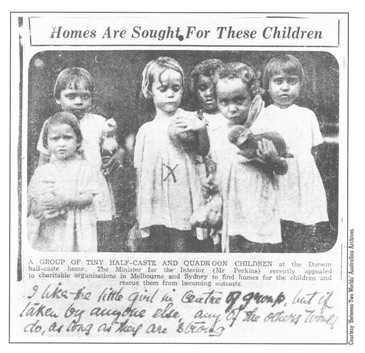

Clipping from a newspaper, 1930…..(courtesy: Creative Spirits)

A group of tiny half-caste and quadroon children at the Darwin half-caste home. The Minister for the Interior (Mr Perkins) recently appealed to charitable organisations in Melbourne and Sydney to find homes for the children and rescue them from becoming outcasts.

The hand-written note reads: I like the little girl in centre of group, but if taken by anyone else, any of the others would do, as long as they are strong.

This is not slightly altered science fiction from some ‘50s pulp magazine, with blue-skinned Martians breeding with green-skinned natives to eliminate green skins. It happened in happy Australia, where in the last century I was Visiting Professor of Art Theory and Glass at the Australian National University in the capital city of Canberra, far from the sea. Although some students may have been indigenous Australians, I did not see any “aboriginals” until I visited Uluru, the sacred rock even farther from the sea. Some were cleaning ladies in the midrange hotel we booked and some were beggars with didgeridoos.

Was the Stolen Generation of kidnapped children the result of misguided do-goodism? An attempted holocaust by stealth? Even Heinrich Himmler never suggested that the Reich could eliminate Jews and gypsies by three generations of intermarriage. This mad attempt at genocide took place under the Aboriginal Protection Act from 1869 to 1969. Finally, Australian prime minister Mike Rudd issued a formal apology on January 27, 2008.

Australia Is a Very Odd Place

Bindi Cole’s video in the small but powerful exhibition she has curated, “Saying No: Reconciling Spirituality and Resistance in Indigenous Australian Art,” consists of a number of indigenous Australians looking straight into the camera and saying “I forgive you.”

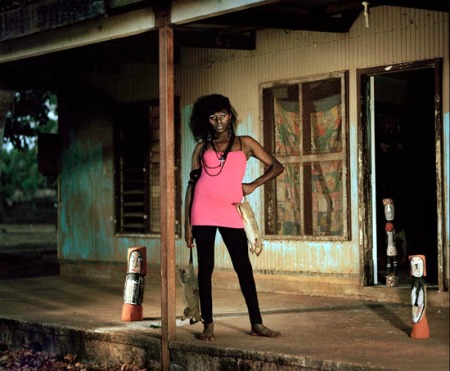

“Saying No” is at MoCADA, a jewel box of a museum near the Atlantic Terminal in Brooklyn, to Nov. 6. Cole herself is of Wathaurung and Australian descent. She won one of the Victorian Indigenous Art Awards of ’09, specifically the Deadly Art Award, for her photo Ajay. It is from her highly styled photos of the 50 indigenous transgender Sistagirls living together on the Tivi Islands, north of Darwin. As a general rule, transgender persons are more acceptable to indigenous cultures than gays. Although none of Cole’s Sistagirl photos are in “Saying No,” here is a link to a slideshow.

I came away from MoCADA wondering if irony is a characteristic of the curator or of Australian art or of new indigenous art. Or all three.

Languages

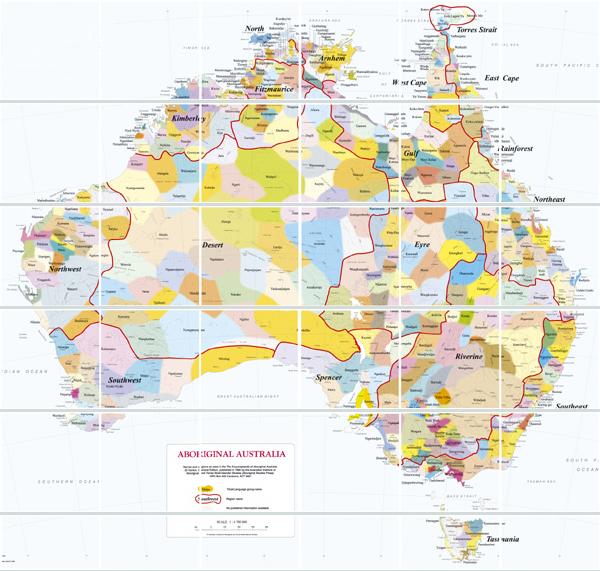

The original Australians had art; they had the Dreamtime religion. And it is certain they had languages. At the time of Western contact — perhaps we should call it the European invasion — there were at least 300 languages and 600 dialects, one and sometimes two languages to a nation. Now only 15 are spoken. Some dialects are “mother-in-law languages” — words you use only when around a close and a particularly frightening relative — and mourning languages, so restricted in vocabulary that sign language had to be invented to complement them.

Please leave the room. Sorry, my grandma died so I can only say “please” and have to make gestures for “leave,” for “the,” and “room.” But what is a “room”?

Some linguists divide the indigenous languages into two dozen families. Or maybe not. How are the languages related or distinguished? Can the speakers of one language understand those of another? In my alternate universe, the sign language required by mourning dialects becomes the Australian lingua franca.

Signs of Life, Signs of Protest

“Saying No” proves we already have an global lingua franca, that of concept-based art. Although presentation must be faultless, it is the idea rather than the form that counts. Here are some fine examples from the exhibition, each one saying no in a particular way:

Tony Albert’s Beyond Belief, a catalog of aborigine stereotypes that could match any U.S. darkie-toons.

Yhonnie Scarce’s Burial Grounds: a display of black, blown-glass bones.

Fiona Foley’s HHH (aka ‘Hedonistic Honky Haters’): Indigenous persons in KKK-like regalia, representing an imaginary secret society(See above).

Vicki Couzens’ Walooyt , an installation of suspended possum-skin bone-bags. Widows had to carry their dead husbands’ bones in these for a year. Also: woorkgunau woorraka kooramook, a latter-day possum-skin burial cloth. Note that the possum is listed as an endangered species in Australia, so all skins have to be imported from New Zealand where they are considered pests.

No, A Thousand Times No

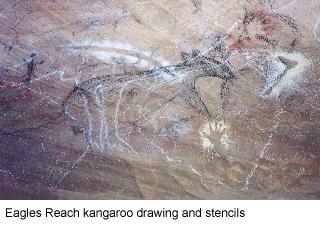

If you think the indigenous Australians always and only lived in the dead center of their island, you are wrong. When the British arrived, the majority occupied much the same land now fully Europeanized: along the shores and along the rivers. Good taste is universal. Everyone wants to live near water. Recently, cave paintings dating back 4000 years were discovered at Eagles Reach, just outside the gorgeous port city of Sydney. There are typical image overlays, but the Eagles Reach magical artworks are not as old as those in the Northern Territories, where sometimes 14 layers have accrued, accumulated every which way. This indicates to me a non-directional Dreamtime. The overlapping Picabia/Salle transparencies show that the act of depiction was more important than seeing the results.

Dating of the 100,000 rock-art sites throughout Australia indicates that the indigenous culture is 50,000 years old: the oldest continuing culture on earth. Does the Eagle Rock art also depict half-man, half-animal therianthropes? For fear of touristic damage or just bad breath, we are not allowed a firsthand look. If you think the remaining indigenous Australians all live in the outback, you are also wrong. About 80 percent of their half million (2.5 percent of the nation’s population) live in the capital cities, just like 80 percent of the Euro-Australians.

This Land Is My Land

I have come to the conclusion that indigenous Australians are not the mystery. It is the Euro-Australians. Since they landed on the subcontinent, they have come up with the strangest ideas. It is easier to understand Dreamtime than it is to understand duplicity. What we translate as “dreaming” or “the dreaming” or “dreamtime” is both an activity and a place where you exist before and after birth — and can sometimes visit while still alive. It is not just a realm of archetypes, but heaven, perhaps like the Pure Land of Japanese Todō Shū Buddhism. What is so hard about that?

More difficult to understand is the cruelty, hypocrisy, and greed of the European invaders and their sheer insanity. The Euro-Australians conveniently ruled that all of Australia was a no man’s land or terra nullius and was theirs for the taking. Could there be land ownership without nationhood in the European sense? No built-up settlements, no cities, just tracts through the “wilderness” remembered by chants? No, of course not, ruled the Down Under courts, using the strictest principles of British law and objectivity. The legalism offered by the British colonists — who wanted all that land for sheep and for the worst of their Irish, Welsh and Scottish convicts — was that since the natives were nomadic they had no concept of property. Therefore they had never owned the land that was stolen from them. Yes, nations of the outback moved from place to place, following landmarks, seasons, and ecologically sensible variants. So they couldn’t be nations. But does this mean they had no rights to the land? Surely Brits would understand hunting and fishing rights. Maybe back home, but not here.

In 2006, an Australian judge ruled that the Nyoonaar people were the rightful owners of the city of Perth. Panic in Melbourne. Panic in Sydney. Turns out, however, that the ruling only really meant fishing and hunting rights and a few sacred sites. Bankers and realtors relaxed.

Follow the Dots

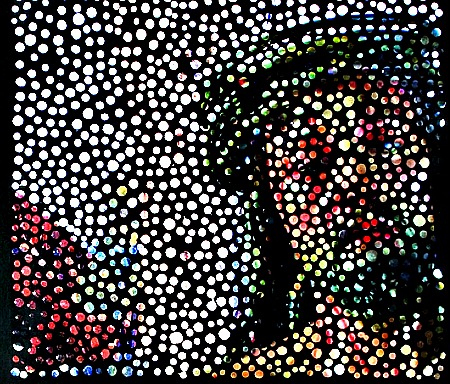

If nothing else, “Saying No” will let everyone know that the popular “dot paintings” are not the only contemporary art being made by indigenous Australians. In 1971, British art teacher Geoffrey Bardon saw Papunya sacred-ground paintings somewhere near storied Alice Springs and suggested that the images be committed to paint on canvas. Willy-nilly, they thus became income-generating product for their impoverished makers. Today, the dotted paintings are a billion-dollar market, replete with second-generation celebrity masters, fakes, and schemes. And with women artists, probably forbidden from making art for 50,000 years. I like the paintings. They look so modern. I have written about them in the context of Tibetan mandalas and Jung’s illustrations for his famous Red Book. Here is a link.

But do these stunning paintings preserve or trivialize the highly coded, sacred dreamings? Is it enough to cover the secret parts with dots? Is choosing between your culture or abject poverty a real choice? Salvation or starvation? To me two of the most important artworks in “Saying No” are Daniel Boyd’s Jesus Christ #1 and #2: Papunya-dot renderings of a cliché image of Christ. He turns the question upside down, inside out, and puts the shoe on the other foot.

Mission Accomplished

But, you ponder, MoCADA stands for the Museum of Contemporary Arts and Cultures of the African Diaspora. Well, never mind that the indigenous people of Australia are not of African descent. Their story is large and resonates, alas, with the fate of indigenous peoples everywhere. What this curiously moving exhibition proves is that art can indeed be used for protest, and even be stronger for it. There is no necessary contradiction between beauty and protest. And as someone once said, there is no contradiction between the personal and the political — even if you are an indigenous Australian, particularly if you are an indigenous Australian.

——————————————————————————————————-

For easy access to 200 previous Artopia essays by topics, go to top bar, click on ABOUT, click on ARCHIVE, then scroll down to listing by Headlines.

NEVER MISS AN ARTOPIA ESSAY AGAIN! FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT perreault@aol.com

John Perreault is on Facebook. You can also follow John Perreault on Twitter: johnperreault

For Art Cops cartoons and other videos on Youtube: John Perreault Channel. John Perreault’s art. Main website.