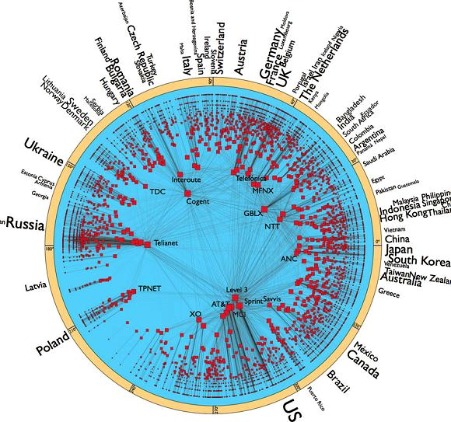

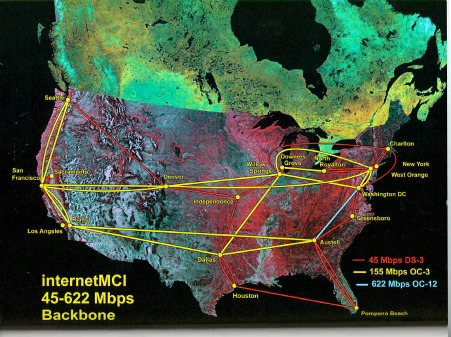

Hyperbolic Internet Map, 2010

Not all museums were alike. But when they

were alike, they were alike in different ways.

John Perreault, 2020

Study Sheet: Art Museums USA

Historically, art museums had several relatively stable and interrelated functions. Nevertheless, this or that museum may have emphasized some functions over others, depending upon its mission, its patrons, its audience, its funding sources*, and its culture. And do not forget the influence of its board of directors or trustees, its CEO, and in some cases even its curators. Museums also changed over time.

Art museums were often civic symbols (symbols of civility), memorials to the super-rich (naming-cleansing or legacy-enhancing opportunities), and purveyors of social (and socializing) amenities. But they also had the following functions, which may or may not have had anything to do with those just mentioned:

The collection and preservation of artworks.

The study and interpretation of artworks.

Art education.

The creation and/or perpetuation of civic and/or cultural identity.

Recreation and entertainment.

The creation and/or the public display of artworks for aesthetic contemplation, inspiration and appreciation.

The affirmation of the social and financial value of artworks and, in fact, of art in general.

Tourism and related income generation.**

Increase and/or stabilization of real estate values.

John Perreault, Jan. 2020 – History of Art Museums 100a

* In fiscal year 2008-2009, the Metropolitan Museum, according to its annual report, available online, received only 13% of its operations funding from the City of New York, the largest percentage of which was free utilities. The Met Museum’s endowment investments provided 35% (a problem during a recession) and admissions 14%. Not counting the indirect (and therefore politically immune) support provided by the forgoing of taxes on incomes and the generous deductions allowed corporate and individual donors, museums in America are expected to go it alone, unlike in other countries.

**In 2010, Glenn Lowry, the director of the Museum of Modern Art revealed that at least 60% of the visitors to MoMA came from abroad.

How It All Happened

No one suspected in 1993 that a military defense network of interlocking computers — designed so that one failure somewhere would not bring down the whole house — would go beyond archive access, file sharing, and commercial, non-governmental e-mail and suddenly, with the invention of the graphical web browser Mosaic in that year, become the information system that changed reality.

By the second decade of the 21st century, art museums became destabilized by the internet. What was the tipping point? That, out of the blue, a few museum directors announced that there were more visits to museum websites than to the physical museums they promoted?

Signs of panic were artfully concealed, but if one does some research – easy with your computer — you’ll discover that alternative futures for art museums were quietly being examined. Members of the American Association of Museums, a professional organization, were offered a newsletter (delivered by email) called “Dispatches From The Future of Museums.” On the surface an aggregate site produced for the AAM by its affiliate, The Center for the Future of Museums, it now offers glimpses into the art “unconscious.” Present-day readers may be amused by a link to a consultant’s screed proclaiming the necessary ingredients for successful Location-Based Entertainment centers. A certain Randy White offered “What’s Next: The Future Is Already Here”:

Migration to the digital world There has been an accelerating shift from out-of-home real world to digital world entertainment experiences and spending. People are spending more time in the digital world. They are living large parts of their social lives online. In June 2009, 23% of Internet time was spent on social networks, up from 16% just one year earlier. From 2004 to 2009, time spent at real world social activities or attending out-of-home cultural, entertainment, sporting or recreational events decreased anywhere from 20% to 50%.

The implication for art museums was that if they were to survive as Location-Based Entertainment centers (which they had willy-nilly become), then they would have to further imitate department stores and shopping malls by making the following changes:

- Use digital technology to fuse the real and virtual worlds by embracing the Multiverse and its eight-realm matrix of the real world, virtual world and time. This includes using the realms of Augmented Reality, Alternate Reality and creating a seamless social experience.

- Offer 24/7 convergent LBE experiences by extending the guest experience by both time and place from the real world into the virtual world.

- Focus less on entertainment as the primary guest experience and brand identity and more on creating enjoyable social experiences that also center around destination food and beverage.

- Offer more upscale experiences, including the quality of the environment, service and food service, to appeal to the higher socio-economic guests who control the lion’s share of out-of-home entertainment spending.

- Offer guests more options to co-create and personalize their experiences.

- Move from mindless entertainment to enriching, educational and meaningful entertainment. Entertainment spending that makes the world a better place is just one aspect of this.

- Offer a compelling and repeatable experience that motivates people to leave the comfort of home and their many at-home entertainment options at a cost perceived as a great value for their time, effort and money.

The opposite to this future, also offered up by The Future of Museums, was represented by David Curry’s One Potential Future of Museums — Thinking About Convergence — i.e., the convergence of museums, archives, and libraries.

The Internet/Web 2.0 is increasingly the “default” platform for interpretive, curatorial and service design strategies. Whatever an institution does in this realm, and however physical assets and content may be employed, the question about “how this gets delivered on the web” needs to be answered. This common platform momentum will drive a new common skill set requirements and an expansion of audiences served in both sector and geographic terms, fostering convergence along the way.

This future clearly privileged archival, communication, and educational values as opposed to entertainment, financial, and sociability vectors. Both futures turned out to be wrong.

Deeper and Deeper Into LBE and HBE

But Perreault was like a dog refusing to give up a bone:

For clarity’s sake, LBE (Location-Based Entertainment) needs to be paired with an oppositional acronym. We must have symmetry! How about HBE (Home-Based Entertainment)? LBE vs. HBE. That would clarify a great deal: restaurant dining versus dinner parties at home; movies projected in a theater versus movies on home TV or computer, live concerts versus CDs or Pandora. Now, because nothing is ever simple, and symmetry is a didactic fiction hard to maintain, we have to figure out how to label live HD broadcasts of the Metropolitan Opera, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Bolshoi and San Francisco Ballet in movie theaters. Not really LBE, but a movie theater in a mall is not HBE either.

Also in the mix, we must consider Home-Based Live Streaming, as above. And soon everything — for a price. Now and then, you can already see the Metropolitan Opera live on PBS; and your father or mother will remember live presentations of Salome (great) and Trouble in Tahiti (yuk) on the TV program Omnibus.

A Prophet in His Own Land

John Perreault, writing in his seminal blong called Artopia, seized the day. At the beginning of 2011 he predicted the ultimate triumph of the totally online art museum. Peppered with provisos, his knot of speculation can be unraveled to a more characteristic braid.

Perreault hoped that physical art museums would at least linger as relics, on the order of opera houses, handy for special occasions and for the display of opulent or intentionally down-market wardrobes, rather than for the enjoyment of live sound and outré performance, styled in any case (as was the staging) for digital “broadcast.”

Art museums, he speculated, would be empty monuments offered as party sites — archival and other duties long since transferred to venues cheaper to maintain, some not even in the United States.

Art education, he felt, was already on the road to success on the internet. He visited and praised the online efforts of the Museum of Modern Art and other physical museums in his native city, New York. There were, he said, no longer any reason to have wall texts or docents in the way of the artworks on display; all interpretive information could be accessed through iPhones, iPads, or at home, before or after the sacred moments in front of iconic artworks in the flesh, as it were.

In retrospect, other game-changers had just occurred. And we can witness them even at this late date through his eyes, thanks to P.L.A.T.O. and L.O.G.O.S. [see below]. One event was MoMA’s, and two others belonged to the flagship museum of the Guggenheim international franchise.

Perreault in 2011 appraised the Museum of Modern Art exhibition of Andy Warhol’s single image, real-time, sometimes virtually motionless films rather favorably (Andy Warhol: Motion Pictures, Dec. 19, 2010 – March 21, 2011), although noting that the artist himself might have been perplexed to see his experimental, “underground” films projected on gallery walls, giving the effect of living paintings. It was likely, however, he would have been thrilled by the attention brought to his oeuvre. Warhol’s intentions, of course, were mostly to bring attention to himself and his product line, no matter the impurity of the modes of replication or communication.

He noted once again that although MoMA had a great deal of information and a lot of programs to squeeze into its website, it was still very difficult to negotiate even using what he had come to call his Apple Brain. He offered the advice that to find the new “screen tests” you had to click on Explore on the bottom bar to Exhibitions then Andy Warhol Motion Pictures then Interactive to see the actual screen tests submitted by the public.

Perreault went on to critique the online component, an audience-participation, make-your-own Warhol screen test:

The differences between looking at the projected Screen Tests at MoMA and seeing the submitted, homemade “screen tests” on your computer are instructive…. Even if we were looking at the real Warhols via the internet, scale might certainly be an issue, if film or digital video has scale. But more interesting is that even on the computer some would recognize the faces from Warhol’s full-length movies like the Chelsea Girls: Edie Sedgwick, Nico, Joe Dallesandro — never mind that in my own case, I sometimes came across the Superstars in real real-life at the Factory or Max’s. Gerard Malanga — Warhol’s prime-time studio assistant — was a poet known by all, at least in the New York School poetry scene. Even if you do not recognize these faces, you must give Mr. Warhol his due. He knew a good face when he saw it. Oh, as someone once said — in another context — they had faces then.

Much longer films — Kiss, Blow Job, and Sleep — are projected at MoMA. But wouldn’t it be great to see all of Sleep on your computer or flat-screen TV? But why then would you later pay MoMA admission fees to watch John Giorno sleep? To get a better look at Giorno’s nose hairs?

The online “screen tests” offer a parade of mediocre self-portraits — perhaps proving Warhol really knew how to chose faces that would register on the silver screen or that faces now are woebegone and have been sucked dry by computer screens. Perhaps it was the translation of Warhol’s “style” to a series of strict rules:

CREATE YOUR OWN SCREEN TEST

STEP 1: Stage your Film Set

Prepare your camera and/or webcam

Set up a solid white or black background

Darken your filming environment, with the exception of a light source shining directly on you

Sit in a chair facing the camera

STEP 2: Record your Screen Test

Start recording

Look directly into the camera lens

Remain as motionless as possible

After your Screen Test is accepted, the video will be displayed on the exhibition website in black and white at a 4:3 size and muted to emulate the style of Warhol’s Screen Tests

At the Guggenheim

Today, the corporate-like expansion of this brand has withered away. The Guggenheim brand had been spread too thin, thus devaluating itself, leaving here and there empty or now repurposed monuments to bad architecture — rather than to painting and sculpture. Museums once counted on being special, but they were no longer so when their branches became ubiquitous and took on the appearance of discount outlets.

In this regard, Perreault in 2011 mentioned and compared Brooks Brothers outlets, then offering huge discounts on mostly inferior goods that never appeared in their Manhattan flagship store to the fewer-in-number Barneys outlets, which mounted infrequent and modest sales, and only then for retail mistakes or loss leaders. And then announced:

McDonald’s may work in Fiji, but a Fiji Guggenheim will only incite riots. Why go to Fiji or Helsinki to see yet another Guggenheim Museum when you already have one at home? Too many outposts gives the game away and occasions disbelief,” opined Perreault. “A better tactic for the Guggenheim world-empire would have been to replicate exactly the Frank Lloyd Wright building in any country that could put up the bucks.

More relevant to our purposes here is his evaluation of two Guggenheim projects that, like the Warhol screen tests, were later to be seen as game-changers.

In 2011, Perreault was less than positive about the Guggenheim’s “YouTube Play” project on the grounds that the jury, in response to an unprecedented open call, had done a poor job (“too much animation!”). He also felt that the presentation at the museum itself (see image above) was merely a ceremonial sop to the sponsor (YouTube) and not a proper way to see the winners or any of the entries. Or was it someone’s lame idea that YouTube videos need to be shown in a physical museum to validate them as art?

Perreault picked out the following videos as exceptional:

Martin Kohout: Moonwalk

(“Your everyday landscape turned into a Mayan temple.” JP)

Perry Bard: Man With A Movie Camera: The Global Remake

(“Meta rhymes for the Net.”JP)

Josh Bricker: Post Newtonianism….

(“Real war vs video game…reality?” JP)

Bryce Kretschmanu: Auspice: (“Save us from Fox News!” JP)

He felt more positive about a Guggenheim dance presentation that was done live on the internet. And he quoted, perhaps sardonically, Guggenheim marketing manager Francesca Merlino, who offered the following shocker:

For the Guggenheim, demographically our audiences are largely international, and it allows us to offer content to people who may know the Guggenheim brand, but maybe will never have the opportunity to visit our physical space….Now we can form new relationships by expanding our content online to a much larger audience than ever before.

Perreault’s comment: “The End Is at Hand!”

But he was enthralled by the actual netcast:

At home I watched a presentation at the Guggenheim Museum of the Works & Process Series online live for the first time: Pacific Northwest Ballet — Giselle Revisited. We watched on our flat-screen because my ingenious mate figured how to make the TV screen our computer screen. We can watch everything available to our computers on the TV. Slideshows, documents from hell, home movies from archive.org, shorts on YouTube, features on Hulu, Lulu, and Hula; even books from Project Gutenberg.

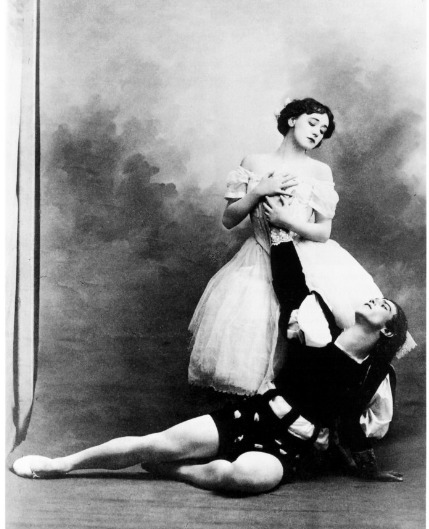

This time we watched dance scholars and four dancers from Pacific Northwest Ballet explain and demonstrate a forthcoming recreation of the original Giselle, more or less based on the archival Stepanov notations, c.1903

No hassle. No subway or cab fare, no dress-up, no live dance critics fidgeting, chatting, whining. No dance fans fanning themselves with ad-ladened programs. No accidental cellphone rings. I could have been naked.

The tension was unbearable. Would the camera move to the screen to the left of the ministage in time to illustrate one of the scores discussed? Would one speaker mispronounce “laden” again, making it have something to do with Alan Ladd rather than bill-of-lading? Would I get the willies from hearing about the Wilis — spirits that figure in the Giselle plot? (Giselle, ou les Wilis was the original title.) Hilarion is grieving Giselle’s death. He is frightened from the glade by the Wilis, female spirits who, jilted before their wedding day, rise from their graves at night and seek revenge upon men by dancing them to death.

You can watch the whole program by clicking on “Giselle Revisted” above. But, trust me, it was better live.

Isn’t everything better live?

The dancers dancing lifted the whole thing, and I was reminded how much I hate mime; the original Giselle was 50 percent mime; so you are treated to silent-movie gestures more than half the time — while you are waiting patiently for the exquisite parts. I also didn’t like hearing that one rotation to the left/rotation to the right was eliminated because the dancer wasn’t comfortable with it. In other words, it was too hard for him. Pity. He did it anyway at the Guggenheim and it looked great; the amended sequence that was demonstrated as well was boring.

The Art Museum of the Future, c. 2011

Museums today? People with white hair, standing in line, gathering in front of masterpieces that would have shocked their grandparents. And, in New York at least, well-heeled healthy people speaking German or sometimes Swedish — men and women in their forties, comfortably, unpretentiously dressed, accompanied by well-mannered adolescent sons or daughters, one to each couple.

Tourism I fear is the price we pay for keeping the doors open at MoMA and at the Guggenheim. And at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This presents a paradox: Apparently they need all those paying customers to keep the art on the walls — and also safely catalogued and stored — but because there are so many paying customers, it is sometimes hard to see the art.

Then too there is the youth hoax Both the New Museum and P.S.1 seem to think that the greying of the world will not effect them, that there will be a constant stream of big-spender, 20-somethings with time on their hands and money to burn and ready to party.

Perreault fantasizes a totally online art museum.

But dedicated online art museums must have Net Art as their mission to make any sense, if sense has anything to do with art or arts institutions, as one might hope. From the debut of Mosaic in 1993 and even for a few years after the 2000 collapse of the dot.com bubble, artists and some museums toyed with Net Art. Net Art even had its very own David Ross. Ross, who later went on to lead the Whitney, initiated the first museum video-art collection when he was at the Everson in Syracuse, New York. Jon Ippolito — who says he was hired by mistake when he applied for a job as a guard – was a Net Art innovator too, when he was associate curator at the Guggenheim. But now, alas, only remnants remain of the Guggenheim efforts. Or of the Net Art components of various Whitney Biennials. The Whitney Biennials, YouTube Play and, alas, “Free” at the New Museum all may have been displayed Net Art in inappropriate places: physical museum spaces.

Nevertheless, the dream goes on. Art available to all for free, anywhere and anytime, at least to all with access to a computer hooked up to the web. Since we remember the rocky road for video art, we are not dissuaded by funding setbacks or failures of nerve in terms where Net Art is concerned. Previous museum efforts were premature.

But, continues Perreault:

Nor are we persuaded that anyone, absolutely anyone, has yet figured out the best way to preserve digital files. The current reality is replete with file decay, language changes, system substitutions, program lapses and so forth. I am told for instance that even though I might be able to open my CPM files from yesteryear, they will still need to be copied to newer and newer systems, as will all my current disks, flash drives and cloud vaults. Print out everything on archival paper is the universal advice. Oh, dear. Librarians and archivists of the world, we have to do better than that. And does Picasa guarantee the perpetuity of my image files? What is the Smithsonian going to do with the Twitter files they have now decided to keep for future historians? Copy them all every seven years? Print them out on archival paper? There are not enough trees in the world for that little project. All 280 entries of Artopia are available on artsjournal.com (by date and headline) and five years-worth on the Wayback part of the nonprofit archive.org, which has sent out a “spider” to capture for archiving every website in the world. But what will happen when someday Artopia folds or fades? Or archive.org can no longer afford to maintain its stash of homeless B-movies, radio shows, Artopia posts and 8mm glimpses of the 1939 New York World’s Fair?

We need a perpetual cloud bank that will routinely and automatically reproduce itself. We need a digital Latin. Since so much is at stake, I have the greatest confidence that these minor problems will be solved.

2013: Interested parties (libraries, museums, governments) came together for a month-long conference and work-retreat. They adopted L.O.G.O.S. as the official archival “Latin” of the internet and all digital media.

2015: After the success of L.O.G.O.S., a similar conference was held to officialize and place into effect funding operatives for the self-perpetuating cloud, now called P.L.A.T.O. The Hedy Lamarr torpedo-guidance system that allowed the internet was used to an even higher degree by P.L.A.T.O. Interlocking cloud-farms replicated and rebirthed all data automatically in mobile and randomized locations, using solar, tidal, wind energies and power vampirized from digital entries, relocations and visits.

L.O.G.O.S.: Logistical Omni-Global Overdrive System; aka UniLaCS (Universal Language of Communication and Storage); aka Globalt.

P.L.A.T.O.: Perpetual Legacy and Territorial Override.

“Vampirize”: to appropriate electricity and other energy units by stealth. Originally known as “amp-erize.”

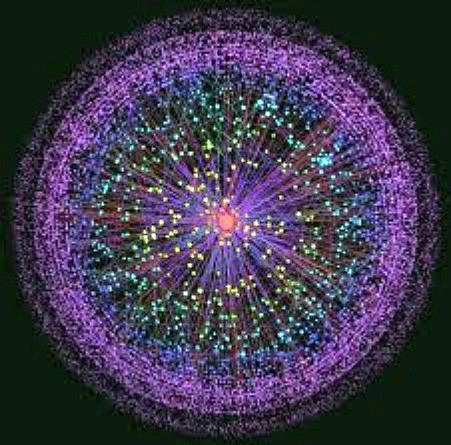

Another diagram of the internet, c. 2010

How and Why Perreault Started His Search for Net Art

We know your search for art on the internet lead to your idea of a totally online art museums, but why did you start that search to begin with?

A Facebook “friend” commented on the drop of searches for “art” on Google that I showed on Artopia. He seemed to think people were looking for actual artworks rather than information about or images of art, and then typed out a mini-rant about the fools who imagined they could find real art on the internet. I couldn’t think of how to respond, but I did think of blocking him or sending him into permanent Facebook exile….But then asked myself, why not “real” art on the internet? Home-Based rather than Location-Based Art, delivered for consumption wherever and whenever you want it? And I have to confess that thanks to the apparently newly discovered Arctic Vortex caused by global warming – I was snowbound in lovely but virtually art-free Long Island that week and suffering from a nasty cold. I needed my art fix. I thought of it at first as a service piece. After all, many are “snowbound” in terms of culture all year round. Shouldn’t we have art for them?

We understand that you included films at first.

I reminded my readers of the films they could see, particularly art films, and embedded three:

Joseph Cornell’s Rose Hobart (1936), 19 minutes of footage clipped from 1931’s East of Borneo starring silent-screen actress Rose Hobart, a Cornell favorite. The film is tinted blue. Cornell, famous for his surreal boxes, seems to have merely removed all scenes that did not show Hobart, but I detect some sequence-juggling time warps. It’s languid and perverse in an innocent way. Don’t know if this was the music when he first showed it. Here is the entire film at Ubu.com.

Bruce Conner’s A Movie (1958), a nine-minute collage of found footage. Surely a masterpiece. Here is the entire film on an

Asian website — tudou.com.

But then there is this rarity — The Great Blondino.

William T. Wiley and Robert Nelson: , 1967. 40 min. Truly strange mix. Lots of shock-cuts, superimpositions, juxtapositions. Dedicated “To tightrope walkers everywhere.”

Blondino (played by Chuck Wiley) dreamwalks through San Francisco pushing a wheelbarrow. Will he actually walk a tightrope like his 19th-century namesake? Among other tasks, our hero, a blindfolded clown, licks the dot of a large question mark and massages a rhino tongue. Clearly he is, as someone proclaims, a worthless, no-account misfit whose “operation is not in the national interest.”

The film was hosted on Art Babble, a kind of consortium of museum videos (but mostly dreaded and deadly, talking-head educational lectures), and I was amused by this posted comment: “Lots of problems viewing. The audio is distorted and visuals seem just to cut in and out randomly. I am using Real Player with a broadband connection. What could be the problem?”

We indeed had a problem. You had to have seen some avant-garde and underground films to know that these “errors” were intentional and call attention to the physicality of the film and the artifice, right? Like the blue tint and the time-warps in Rose Hobart? Like the sprocket holes in the Bruce Connor?

Didn’t you also investigate Twitter for signs of art?

Yes, indeed. I offered the number of “followers” some artists had accrued:

Vito Acconci 585

Nayland Blake 591

Barbara Kruger 1,920

Jenny Holzer 24,661

Tracey Emin 4, 449

On Kawara 1, 575

Bruce Nauman 83

Jeff Koons 1,378

Yoko Ono 1, 164, 201

Lady Gaga 7,794,510

John Perreault 131

And if you will permit me to quote myself:

Lately I have been following and posting on Twitter, trying to figure it out for Artopia. A few artists have sites that are inactive (Vito Acconci). Or too strange or not strange enough (Nayland Blake: “Stop by Sue Scott Gallery tonight for the premiere of UNPUNISHED: a queer ‘zine one-shot curated by yours truly.”). There is a “Tracey Emin” Twitterer I follow; sounds like her, but could be fake since now she is just plugging Royal Academy lectures. She may be a pseudo-Tracey, just as the consensus is that the Damian Hirst on Facebook is not the real deal.

Yoko Ono — who has over a million followers — is “verified” as actually being Yoko. And it surely sounds like her, with all her back-and-forth shifts from greatness to sentiment. Doubt that anyone can fake this:

[ Let’s visualize all the people living life in peace. 10 seconds. One hour. All day. Anywhere and anytime of the day.] She also branches out weekly to a brilliant Q & A that can be surprisingly wise. I hate to say this but I prefer her to the Dalai Lama, whom I finally unfollowed, although I am not sure what that means about Tibetan Buddhism or me.

Jenny Holzer, who does not follow anyone herself, emits her pithy sayings periodically:[FEAR IS THE GREATEST INCAPACITATOR]. Am I the only one who prefers Barbara Kruger’s pithy sayings? [THIS STUNNING ENSEMBLE SAYS YOU’RE NOT WHO YOU THINK YOU ARE].

And why do I find it soothing to find out now and again that On Kawara (“I am still alive.”) is still alive? And how can you not love Lady Gaga?

[I can’t believe#GodMakesNoMistakes is trending. I hear u + becuz of u the world does too. Can’t wait for u to see what I’m doing right now!]

Now that I think of it, when, if ever, will my ongoing investigation of innovative residential architecture go viral?

I think you also found Twittering Colors somewhere and posted it.

Yes. At first it looks like a Gene Davis stripe painting, but it moves and constantly changes as people tweet. It’s still going. I found out it was by Brian Piana and was part of a Glasstire Vertual Residency. Glasstire is a Texas online magazine named after Robert Rauschenberg’s glass tire which I facilitated when I was at UrbanGlass in Brooklyn. When you log on to the Twittering Colors site the instructions are at the lower left of the screen.

Do you have anything else to reveal to us, now that your predictions have come true?

I think it is worthwhile quoting how I ended my piece in 2011:

Why Wait? The DIY Digital Museum!

Keep this in mind. Mosaic, the first browser with graphic capabilities, was invented in 1993. The internet as we now know it is less than 20 years old. Build a museum for pebbles and pebbles will accrue. Art hates a vacuum. Already there are clues to what online digital museums will look like. The cat is out of the bag; in 2010 more people visited museum websites than physical museums. The educational tail is already wagging the dog.

The Whitney has left up its Net Art resource list of links called Artport, which is well worth investigating although like everything else in the first flush of Net Art it stops at 2006. And turbulence.org, which does not stop at ’06, is already almost a museum of Net Art. At the Whitney I found three commissions of note, done in collaboration with the Tate, in 2006 —- all “interactive.

Andy Deck: Screening Circle (“An interactive, digital quilt.”JP)

Marc Lafia and Fan-yu Lin: The Battle of Algiers (“The movie moved around…by you.” JP)

Golan Levin with Karmal Nigam and Jonathan Feinberg:The Dumpster (“Dump notes by teens…every letter a broken heart.” JP

And through turbulence.org these:

Benjamin Gaulin: Corrupt Software (Scary!)

Leonardo Solaas: Google Variations (“The Google Pages from hell!” JP

Scott Kildall: Playing Duchamp (“The Dada challenge; all moves based on Duchamp” JP)

NEVER MISS AN ARTOPIA ESSAY AGAIN!

FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT E-MAIL perreault@aol.com

John Perreault is on Facebook.

You can also follow John Perreault on Twitter: johnperreault