Oliver Herring Is Ready for His Close-up

Walking into Oliver Herring’s recent exhibition titled “Areas for Actions” (October 7 to November 6 at the Meulensteen Gallery) was like entering a particularly messy photo shoot. People and cameras everywhere. An environment of materials and props. Splashes of color on the walls and windows. A scantily clad young man and a scantily clad young woman, supine on the floor, were slowly being sprinkled with glitter by the fully clothed artist, identified by a mutual friend who later introduced us. I don’t know what I expected, but I was certainly surprised, and, I confess, initially confused.

On the strength of my memory of Herring’s knitted Mylar pieces and his photosculptures, I had the month before nominated his show, sight unseen, for one of critic David Cohen’s “Review Panels” at the National Academy Museum. I pulled Herring and two others from my handy must-see/will-see notebook that I use to map and schedule my forays into the real world of art in galleries and museums.

Cohen’s clever gimmick here is that three art-worlders (in October it was artist/writer Greg Linquist, ARTnews’ Barbara MacAdam, and myself) chat live with him about four exhibitions that the paying audience has had an opportunity to view in advance.

As if by magic, two of my nominations stuck to the wall — Herring at Meulensteen and, alas, Guillermo Kuitca at the new Sperone Westwater space architected by Sir Norman Foster.

Except for the 1992 mattresses (Le Sacre) in the gigantic elevator-gallery (“moving room”), the Kuitcas on display were dull. The exhibition was a snore, but the building a success.

I then trounced the dull, dull, dull and awkward, overpraised painting of Suzan Frecon at David Zwirner (who was also on our assignment list), as a hideous marriage between Georgia O’Keeffe and Mark Rothko. This was not well-received. Frecon is our new Anne Truitt. In short: Looks better in photos than in real life. One wants to like her work, but she doesn’t really deliver.

But I did fall for Liz Cohen’s hybrid car at the new (and dramatically designed) Salon 94 on the Bowery, launched by TV star (Work of Art: The Next Great Artist) Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn.

Salon 94 in its new incarnation is right near the New Museum. You walk down a single uninterrupted flight of stairs into the two-story underground exhibition space, in this case, splendidly theatricalizing Cohen’s zany Trabantimio — an East German Trabant and a Chevy El Camino “hybrid” the artist engineered herself. You could say that the artist specializes in body work. As a photographer, she once did a series focused on transgender sex workers in the Panama Canal Zone. As part of the Trabantimio East/West project, Cohen hired a trainer and transformed her own body so it would be suitable for the pinups accompanying her “convertible” when exhibited at low-rider meets. The Trabant expands and almost turns into an El Camino.

But Oliver Herring? He knocked my socks off. My hand-knitted socks.

Eternally Emerging

Herring’s series of 21 eight-hour “Actions” at Meulensteen presented a sampling of what he has been up to in terms of his “Performative” work, instigated here and there around the country in galleries, museums, and art schools

Herring: FluxTASK at FluxSpace Philadelphia, 2007. 400 plus participants.

When was the last time you saw actual performance art in a commercial gallery? Vito Acconci’s Seedbed at the Sonnabend Gallery in Soho in 1972? Technically, it was heard, not seen.

Herring’s “Actions” at Meulensteen brought many viewers (including yours truly) back several times and I don’t think it was the novelty. Charming, puzzling, odd, benign — we couldn’t get enough. When I Facebooked Herring’s Color Spit Group video clip, someone responded that Herring was Warholian; another commented that I had to be kidding and it was the silliest thing he had ever seen. I permanently hid the latter “friend” (1462 friends and still counting, pulling ahead of Arthur Danto but not yet Jerry Saltz or Lady Gaga). It was the now-banned “friend” who made me realize I was on to something.

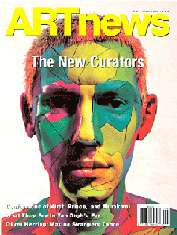

Born in Heidelberg, Germany; educated at Oxford and then here in New York at Hunter College, Herring is now all of 46. So technically he is not an emerging artist. One of his photosculptures was on the cover of ARTnews in 2009, along with an excellent profile inside.

Herring arrived at art by default. He was always good at drawing, but it wasn’t his main interest as a child. He remembers going as a teenager with his parents to an opening of an installation by Joseph Beuys — a controversial figure in Germany at the time. Herring hated the show, which was filled with little pieces of dried sausage, felt, and fat, until Beuys himself arrived and talked about the work in very accessible language. “That was a powerful experience because I looked at something and then I looked at it again and it was totally different.”

– Hilarie M. Sheets, ARTnews, Sept., 2009

Herring is probably still best known for his hand-knitted sculptures using Mylar tape to commemorate drag performer Ethyl Eichelberger.

Untitled (Flowers for Ethyl Eichelberger), knit Mylar, variable dimensions

In the early 1990s, Oliver Herring was one of the first artists who chose to express himself exclusively through the medium of knitting. The two knit coats displayed here are part of an ongoing memorial project called Flowers for Ethyl Eichelberger (1991-1994). They were hand knit using silver-coated Mylar strips, which were created by cutting up luxury shopping bags. These glamorous items of clothing, whose gender affiliation remains unclear, resemble theater or circus accessories. They allude to the unusual figure of actor, camp playwright and drag queen Ethyl Eichelberger — a central presence on New York’s alternative fringe scene — who committed suicide in 1991 after a struggle with AIDS. The ongoing process of knitting, which marks the passage of time, was compatible with the emotional character of Herring’s homage to this unique and beloved figure, and was perceived by Herring as a form of activism related to the struggle against AIDS.

— “BoyCraft,” Haifa Museum of Art, 2007

Chris After Hours of Spitting Food Dye Outdoors, 2004

c-print, 41 1/2 x 62 1/2 inches Framed, Edition of 5.

Yet, he has also received favorable reviews for his photosculptures and other works:

Capitalizing on the organic, generative nature of his work, Herring pushes his post-Minimalist process-oriented aesthetic center stage, where the formal concerns of repetition, mutation, and metaphor are taken apart and reanimated.

— Mason Klein, Artforum, 2002

Tim Hawkinson, Tom Friedman and David Hockney are clear precedents here, and there’s a weird similarity to the collaged photo-portraits made by the character Claire on the television series “Six Feet Under.” But part of the modest yet determined strength of Mr. Herring’s work stems from the way he plucks ideas from the air and makes them his own.

— Roberta Smith, New York Times, 2004

…[his]willingness to challenge convention has produced work of exceptional originality.

— Michael Rush, Art in America, 2005

Herring has had museum shows. “Dírections: Oliver Herring” was at the Hirshhorn in 2006.

And there was a survey of 15 years of his art (“Oliver Herring: Me Us Them”) at the Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum, Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, New York, in 2009.

He has been interviewed by Robert MacNeil, but matched up (for contrast?) with Laurie Simmons, of all people.

Watch the full episode.

50 Is the New 30

Herring is eternally emerging. And he is not the only over-40 artist in this category. Nowadays you can still be an emerging artist even if you are in your mid-forties. Why is this? Some say there are now too many artists to process. I say the old processing methods don’t work. “Young” used to mean cheap with investment potential; young now means MFA Art: lookalike artists and their lookalike art.

Auctions rule. Artists, as if by magic, become more and more visible as their auction prices climb. We still put our artists on a pedestal, but the pedestal is the same size as it was five decades ago: room for only 12. Someone jumps on; someone else has to be bumped off. If there is, as I think, a finite amount of money for art, then the small number of high-priced winners gobble up most of the cake. Everyone else grovels for crumbs.

Furthermore, there’s very little art criticism worthy of the name. Theory destroyed stupid art by stupid artists but could not destroy the stupidities of “theory” itself and the use of language to obfuscate rather than illuminate. Sounding serious became more important than actually being serious.

Finally, the history of art since 1945 hasn’t been rewritten, as is now required. There is a refusal to utilize the necessary conceptual tools that are available — imagining art history as a braid rather than a ladder; picturing art as existing outside and/or above and beyond the art market, and likewise in regard to academia; the reconfiguration of the relationships between art and life; using the sociogram rather than the family tree to visualize stylistic and other relationships.

It is rare indeed that you come across an artist who both pleases and provokes, who makes you rethink some of your assumptions. His career trajectory doesn’t fit the mold, nor does his art. He has moved from object making to performance. In the past it has usually been the other way around, with artists cashing in on notoriety. Nor do his TASKS, “Actions”, or performances conform to academic standards. That’s why I like Herring’s work.

#1 Erroneous Presumption #1: Art is not about self-expression.

That strain — the Expressionist strain — had come to a frazzled end and went back into hiding, at last. We were not supposed to understand that Minimalism (say, of Judd, Flavin, LeWitt) did indeed express something: a lack of affect and affection and, contrary to whatever political beliefs these men had and even acted upon, a disengagement with the world. But, oh yes, sans the unavoidable Platonic reverences that clean geometry forces. There is safety in numbers; there is neutrality in geometry. Postminimalism used irregular forms to express the same retreat and, at the time, the required cool, turning another back on the art of the ’50s and the political and sociological uproar of the ’60s. And self-expression? Too much like art therapy! Excuse me; the world needs all the therapy it can get. I am not sure that art alone will make you whole, but it probably does a better job at this than psychotherapy.

Herring sees himself, in part, as offering platforms for self-expression. How totally uncool. Hoorah. In Philadelphia he garnered over 400 volunteers for a TASK event.

Even for his gallery “actions” at Meulensteen he only used volunteers and — here’s the kicker — they keep coming back for more, which for him is proof enough that he is on the right track. Everyone craves self-expression; everyone wants to leave a legacy. And this is the Warholian aspect: everyone is a star, everyone is immortal.

And Herrings own self-expression? The carpal-tunnel inducing exercises in obsessive knitting were a personal response to the AIDS crisis.

We will have to leave the full complexities of Herring’s photosculptures for another time. My guess is that they have something to do with getting close to a stranger through the peephole of the camera and than immortalizing that closeness for reexamination through collage, bringing photographs (2D) to “life” (3D).

In much the same way that Paul Thek during his European period re-used certain works (like Fishman) for various installations, Herring at Meulensteen quoted his photosculptures: close-up photos of a model are reassembled on a Styrofoam armature to portray the model, thus putting the photo back into Photo-Realism.

His new variant (performed Oct. 9 and called Cut-Out Male B) conformed to the printed description: “A male participant’s entire body will be photographed in advance of the performance. During the performance the printed images will be applied directly onto the performer’s nude body.”

Cut-Out Female A was performed on Oct. 13. Cut-Out Male B on Oct. 22; Cut-Out Male and Female Nov. 5. Now the model becomes the armature of his/her very own photobody, photosoma.

In reference to the knitted Mylar pieces, Untitled (Closing Party) had the following instructions: “A group of 6-8 participants will each knit a sheet of circular yarn that is also connected to two of their neighbor’s sheets. In order to gain a stitch a performer has to unravel fabric from a neighbor. Gains and losses will be visible through changes of color.” Unpack this one, if you dare.

Mylar Duet (Oct. 12), and Mylar Group (Oct. 20) were other daylong actions employing what once was Herring’s signature material.

Only one of the 24 8-hour performances referred directly to Herring’s TASKS: (Summary). A group of participants created a self-generating performance without Herring, generated from ideas from the exhibition’s previous performances. The TASKS themselves are seeded by instructions by Herring and then by the performers themselves. The performers replace Herring’s instructions with their own.

Herring must find some self-expression in the success of his efforts at enabling, facilitating the self-expression and the personal art-legacies of others….Dr. Herring. Do we not understand or have we simply forgotten — in spite of Joseph Beuys — that the artist is primarily a healer? Not a producer of trinkets and investment chits, but a healer……

Erroneous Presumption #2: The idea of post-studio art is weak.

Herring told me he has not made art in his studio in over two years. He travels from exhibition site to exhibition site, from venue to venue, making his art in public, as it were. Post-studio art is not a fantasy, but it does require a leap of faith and a reordering of art practice. Herring moved slowly in the post-studio directions, shifting from the production of objects to photography and video that document TASKS and actions. He hadn’t liked working alone, so he opened his studio to others and then he took himself and his cameras out into the world.

If you think post-studio art is weak, imagine an artist beginning in this mode and devoted to it exclusively. Does he or she invite a gallerist or a collector or a critic to come over and look at a series of photographs? What is there to sell? If this makes you nervous, then I have proved my point. Post-studio art, no matter how much it may be descended from the work of some of the Earth Artists and other site-specific sculptors and even some of the conceptualists, is still a challenge for the system. Smithson did, after all, produce those non-site bins of rocks and mirror pieces. As much as I cherish his Earth Art, on some level Smithson was a coward. But then again, he did not teach and so had to make a living. For true exemplars of Post-Studio Art we have to think of Allan Kaprow, George Brecht. And performance artists like…well, you already know the list.

Erroneous Presumption #3: Performance art is over.

On the contrary. Performance art is too well-established to write off. It would be similar to saying painting is over. There are still too many changes to be rung, too many possibilities for hybrids and varieties: new ways of seeing time, the body, the meanings of actions and activities.

Oliver Herring’s work reconfigures the prevalent narrative of performance art that, no matter what the intentions, insists upon a fine line going directly from Futurism to Dada, to Happenings to Beuys to Vito Acconci to Marina Abramovic. This is, I confess, better than ending up with Laurie Anderson: going from the rowdy to the slick, from apocalypse to theater. It is all much more complicated than that. Everything always is.

Here is a clarification that might help:

Performance art is an art form or medium and not a genre or a style. It belongs to the same classification system that includes and separates painting, sculpture, video, photography and so forth. An artist may specialize in performance art, just as he or she may focus on painting or sculpture or, as is sometimes the case, may work in several of these forms simultaneously.

Performance art is not in the same classification system that separates Cubism, Dada, Futurism, Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, Minimal Art as discrete styles. Styles can find expression across the board, in any or all forms and even in various genres, i.e. still-life, landscape, portrait, etc.

Performance art is not a style. Loose lips, including my own, sometimes make that mistake, which then leads to even further mistakes…like thinking that it all began and ended with Happenings, which would be like saying painting began and ended with Cubism or the still-life.

Once you see that performance art is an art form and not a style or genre, it is easier to see Futurist Theater, Happenings, Fluxus Events as styles of performance art, each with its own peculiarities and distinguishing features. A few of us in the late ’60s tried to make “performance art” a style or a movement, or a separate genre. Marjorie Strider coined the term and Scott Burton was enthusiastic, although at first he preferred “theater works.” The term stuck, but

not to us. It was appropriated to mean everything from stalking people in the streets to standup comedy.

Performance art is a time-based art form that involves the actions of live performers within an art context, either by site or designation. So Herring’s recent works at Meulensteen were no doubt some sort of performance art. That they also involved ephemeral sculptures and perhaps site-specific paintings — in the meantime generating lots of video and photography — is part of his mix.

Herring: Phosphorescent Group (Oct. 28, 2010)

Herring’s Innovation

It should now be apparent that we experience Happenings and Destruction Art only through dim and dim-witted photographs and scratchy snatches of film often marred by the camera-wielders trying to make an artwork in the process of memorializing the work in question. Or through words, which are often better than images. Re-creations seem not to work.

What Herring has done is take charge of the documentation, but even more important, he makes that photography and videography an integral part of his live presentations. During Herring’s recent 8-hour actions, he sometimes wielded a still camera himself, but more often directed others with theirs. And he certainly gave direction to the videographer as well as the performers. He pasted, he sprinkled, although his own body was out of the picture. He directed.

To the cameras: to the left; to the right; closer; further back.

To the performers: more phosphorescent paint, to the left; to the right; spit at the window, spit on the wall, spit at each other.

Herring did not use a megaphone or bark out orders. But in his mild-mannered way, he was in charge. Even when he was spending hours sprinkling holographic glitter on two nearly naked volunteers, he commandeered all lenses. And later he alone would select the photos to be printed and would edit the videos. Unlike Yves Klein, who was really at the charismatic center of his actions, Herring’s presence is unassuming. But his aura is embedded in all the photosculptures, photos and videos. All of them. The printed photos and the web-posted or exhibited, edited videos are emblems of the events he instigates.

This then is Herring’s brilliant ring on Happenings: performance as photo-shoot. And we who are witnesses, we who wander into the gallery, are part of it too.

The odd thing about Herring is that he is so original. It is not that his work is reference-free. It delicately alludes to work of other artists. It is not that everything he does works. How could it? He is experimental. His originality is subtle and it probably has more to do with persona and character than — the brilliant photosculptures notwithstanding — the invention of forms. It is sweet work, so one might think of David Hockney or Red Grooms. But one would be wrong. Instead one should think: Joseph Beuys meets Henry Purcell. Herring is a catalyst, a facilitator, allowing others to express themselves.

Herring: Mondrian Miek (Oct. 29, 2010)

Where Does Herring Fit?

Classifications in Artopia are not pigeonholes, but clarifications. Yet even we ourselves must be reminded of that. How then might we place or pinpoint Herring’s “Actions” within the panoply of kinds of performances that performance art has become?

Herring’s “Actions” have the messiness of the original Happenings. Stuff piles up, is flung, hung and all but sung. But words appear, if they appear at all, on slips of paper. More like Happenings than Fluxus Events, they nevertheless sometimes partake of the Fluxus instruction: pull an instruction out of a box. But unlike Fluxian theater, the results are rarely singular or solo. Instead they are free-floating, multiple, dense and definitely not ironic. Furthermore, Herring’s “Actions” at Meulensteen were not confrontational like Destruction Art. His attack on the object is more playful.

And unlike the performance art of Burton (who, with the exception of his Street Works, offered his timed art in the strict context of seated audiences), Herring avoids references to theater presentation. Audiences are viewers and are allowed to come and go like visitors to any art exhibition. Oldenburg and Kaprow sometimes allowed the residue of their Happenings to be viewed as installations, and planned some of them that way. Beuys’ famous lecture to a dead hare was time-bound, but his I Love America was time-bound only by the length of the exhibition slot; viewers were free to wander in and out at will to see the felt-draped artist living in a cage with a live coyote, as if they were visiting a show of paintings or sculptures. Later, however, most of the performances that developed out of Happenings and Fluxus tended to feature the artist himself or herself as a solo act.

Herring as onstage director/dramaturge is also integral to the real time “Actions,” but never as an actor/performer. Or is his benign presence an act?

You know he is there and you know you are watching someone special.

His presence is notable for willfulness and concentration. You see him thinking. Sometimes he greets a friend. Then and only then does he smile. But even in slight acts of sociability, the frame is not broken, the illusion is not destroyed. He places photo fragments on a nude model: he sprinkles glitter. And sometimes he just stand aside and gets out of the way.

The illusion is that making art is the easiest, most normal thing in the world. And in some sense it is. At least in Artopia. You have to concentrate; focus; think. But it’s no big deal.

Herring’s “Actions” are like group meditations rather than some anti-audience, anti-viewer, sacrificial rite.

Herring’s “Actions” also need to be seen in the context of the Anti-Form of Robert Morris’ Continuous Project Altered Daily, itself preceded by Kaprow’s Happening-residue installations and Oldenburg’s The Store, and possibly even Thek’s recently rediscovered European installations that changed from day to day as he worked on them.

There is a lot to unravel here. (I hate to use that term because of Herring’s association with knitting.) But it is nevertheless the case. For instance, you could not look at some of the performance residue on the gallery walls without thinking of Klein’s body prints; you cannot view the videos of the spit pieces without thinking of Bruce Nauman’s Fountain. And yet it all adds up to something else.

Something elusive and, yes, something ethereal, something playful. Something new.

Herring: Untitled (Spit Painting on gallery wall). Water food dye, 2010. Photo, John Perreault.

NEVER MISS AN ARTOPIA ESSAY AGAIN!

FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT E-MAIL perreault@aol.com

John Perreault is on Facebook.

You can also follow John Perreault on Twitter: johnperreault