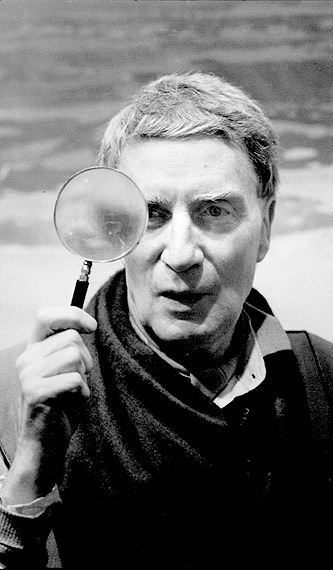

Brion Gysin: Self-Portrait, 1961.

Photo: Courtesy of Musée D’art Moderne De La Ville De Paris

Lift the bandstand!

—Thelonious Monk to Steve Lacy.

Lift the grandstand!

— Artopian motto.

Master of All Trades

Brion Gysin (1916-1986) was a restaurateur, a raconteur, a provocateur, an entrepreneur. A novelist, journalist, promoter, poet, painter, magician. These are only some of the strands in the braid of his life

His multiple talents and multiple roles is what gave and — alas, judging by the weirdly cautious reviews of the New Museum retrospective (“Brion Gysin: Dream Machine,” to Oct. 3) — continues to give the categorists so much trouble.

Categorists: Our enemies trapped inside the categories they themselves have created or perpetuated, who can “see” only by using categories; who control themselves and others through categories.

Classification is pacification.

Playing more than one role is not allowed — emphasis, of course, on “playing.” Playing is not serious. Now that we are living longer, we are free to be many different people in one lifetime. Stockbroker, father, poet. Doctor, poet. Housewife, sculptor. Cartoonist, painter. Restaurateur, novelist, poet, literary agent, dogcatcher.

But simultaneously?

It is as if we were all born with one and only one suit of clothes, one pair of shoes. Oh, please. The reality is that we are multiple. That still puzzles the packagers and the academics. Both deal in sound-bite identities; the latter defending their totems and their turf to the death — of art.

Leonardo da Vinci is celebrated as a painter, sculptor, architect, musician, scientist, mathematician, engineer, inventor, geologist, cartographer, botanist; Michelangelo as a painter, sculptor, architect, engineer and, besting Leonardo, a poet. And then it was all downhill, as art became the arts, as creativity was divided into seminars and seminaries and cemeteries, each policed.

I am not saying that Gysin is our Leonardo or our Michelangelo; far from it. But he should now be reckoned with. As we go about rewriting the recent past — which, given our current, evidently end-game predicament, is increasingly necessary — Gysin will have to be included. Why he has until now been neglected, and what he stands for, once understood, could point the way to one possible future for art, or two, possibly three. New futures for art is what we need right now.

Gysin: Autoportrait, 1935

La Vie Boheme?

First of all, let’s get this straight. Brion Gysin is not a fictional character made up by his buddy William Burroughs. On the contrary, he was invented out of whole cloth by John Clifford Brian Gysin, born 1916 in Buckinghamshire, England. Raised in Alberta by his Canadian mother but sent to secondary school at Downside Catholic College in England. Dad was Swiss and missing in action during the First World War.

By the age of 19, deft at languages, tall and handsome, Brion is a Parisian and a Surrealist, introduced to the cult by Leonor Fini or, depending on whom you read, his older, art-critic lover Nicholas Calas. Yes, the same Nicholas Calas who later wrote so perceptively about Rauschenberg and Johns and who now and then still managed to wave the Surrealist flag in America, even in the ’50s and ’60s. Yes, the Nicholas Calas who in 1951 praises his ex, a would-be Rimbaud to his would-be Verlaine, as “The most promising painter of his generation.”

But in 1935, young Brion is quickly excommunicated from the Surrealist fold — for making fun of Pope André Breton or because he was unashamedly gay. Perhaps both. His works are yanked from a Surrealist exhibition by none other than poet Paul Éluard by order of Breton himself. Brion is crushed. But only temporarily.

Back in the New World, shape-shifter Gysin investigates the Harlem Renaissance. Compromising his poète maudit pedigree, he is, during this most shocking period in his life, the costume assistant for seven Broadway musicals. But his reputation is saved. He becomes a wartime welder in Bayonne, New Jersey, simultaneously continuing artmaking, sharing a studio in New York with the Surrealist Matta. Then, good at languages, courtesy of the U.S. Army, as fate would have it, he studies Japanese and Japanese calligraphy, the latter later important to his art, as we shall see.

During his doughboy downtime he becomes an erstwhile contributor to black history by finding the memoirs of the model for Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and writing and publishing the real history of the real Uncle Tom — a book called To Master: A Long Goodnight, The True Story of Uncle Tom …. which he then tries to turn into a Broadway musical, modeled after Show Boat.

Postwar Warlocks

Postwar Warlocks

After World War II, Gysin is one of the first Fulbright scholars. Then, hired as translator, he tours North Africa with composer/novelist Paul Bowles. They discover the Master Musicians of Jajouka.

Gysin thinks the purpose of Jajouka music is to preserve the balance of male and female forces. Because it is the music he “wants to hear all the time,” he, of course, starts a jet-set, expat restaurant in Tangier featuring these obscure and rarified but spectacularly joyous Muslim musicians.

He is convinced they are actually perpetuating pre-Muslim evocations of Pan. Is this true? According to the Jajouka musicians themselves, their baraka or spiritual power comes from the Muslim saint Sidi Ahmed Sehikh (who left Persia c.800 AD).

Gysin’s restaurant, called 1001 Nights — advertised in the Tangier Gazette: as “1001 Arabian nights food, music, dancing. Floor Show 10:30-11:30” — also features dancing boys and at least one movie-star wedding (Corinne Calvet); yet when super-rich Barbara Hutton, temporarily ensconced in naughty Tangier, goes on a diet and fails to show up for supper, profits take a dive.

Either through some derring-do by a pair of rich Scientologists (John and Mary Cooke) or a Moroccan curse put into effect by a bundle of trinkets and mysterious inscriptions hidden in a wall by a musician, dancer, or Moroccan boyfriend, the legendary nite-spot closes. Not insignificantly, Tangier is no longer an International Zone but part of Morocco, which is now independent. You can no longer easily stoke your hash pipe. You can no longer “rent a hunk” with equanimity. The land of André Gide is perhaps no more.

[The Artopia Quiz: What other artists operated restaurants? — see below.* ]

A Life That’s Spliced

There was something dangerous about what he was doing.

— William Burroughs.

Back in Gay Paree, Gysin eventually becomes the pioneer of the literary cut-up. Although adding-machine scion and ex-junkie William Burroughs (whom Gysin meets by chance in the street) has the provocative insight that writing preceded speaking, our antihero, more grounded, understands that writing, nevertheless, is 50 years behind painting. To remedy this he proposes to apply the painters’ techniques to writing.

He pulls the cut-up out of Tristan Tzara’s Dada hat and creates something new in the world. His close friend (not his lover, by the way) Burroughs runs with the ball, while Allen Ginsberg stands behind and worries. And then the Beatles and the Stones use the method in their lyrics and sound-collage. Others think the cut-up is old hat. Actually, it came from a different place: outer space.

Here is an early Gysin example:

It is impossible to estimate the damage. anything put out up to now is like pulling a figure out of the air.

Six distinguished British women said to us later, indicating the crowd of chic young women who were fingering samples, “If our prices weren’t as food or better, they wouldn’t come. Eve is eternal.”

(I’m going right back to the Sheraton Carlton and call the Milwaukee Braves.)

Miss Hannah Pugh the slim model — a member of the Diners’ Club, the American Express Credit cards, etc. — drew from a piggy bank a talent which is the very quintessence of the British Female sex.

“People aren’t crazy,” she said. “Now that hazard has banished my timidity I feel that I, too, can live on streams in the area where people are urged to be watchful.”

A huge wave rolled in from the wake of Hurricane Gracie and bowled a married couple off a jetty. The wife’s body was found — the husband was missing, presumed drowned.

Tomorrow the moon will be 228,400 miles from the earth and the sun almost 93,000,000 miles away.

— from “First Cut-Ups” (September 1959);

And a cut-up made from a cut-up screed:

Ears behind paintings; use to writing: things or montage. Cut right into . . . lengthwise. Put them together are sage. Do it for your to you. Take your own words of anyone. Words don’t belong to own and you or anybody aims to set the words to spin. The words of a potent ripple of meanings whin (sic) they were struck and posed to liberate.

– from “Cut-ups Self-Explained.”

Gysin and Burroughs thought the spell of language could be broken by slicing, dicing, and splicing. Were they right? Yes, language is a prison. In Artopia we say your own words are the biggest prison of all. The things you tell yourself and the things you write are how you write yourself. These are the first words that need to be unspelled.

Burroughs claimed the cut-up method sometimes results in vaticination. But what should we call cut-up prophesy? I go through a glossary of divination, from alomancy (table salt) to tiromancy (cheese), and the closest I can find for cut-up precognition is, not psychography, a form of mysterious writing perhaps suited to Gysin’s calligraphic paintings, but (1.) stichomancy, which involves opening a book at random and, better, (2.) rhapsodomancy, wherein the book must be a book of poetry. The latter is not, as you may have thought, the use of arcane forms of sodomy.

On the other hand, what novels of the period compare to Gysin’s The Process or Burroughs’ Naked Lunch? Nabokov’s Lolita? Lady Chatterley’s Lover, weak Lawrence belatedly published? Probably only On the Road.

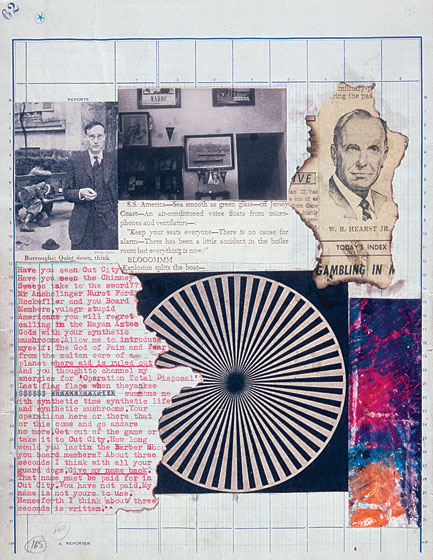

And then, when the boys started being cut- ups themselves, leading to The Third Mind, pages of which fill the center of the New Museum show …well, no one has caught up yet.

Isn’t it time we dump Philip Roth, John Updike and the lot? Continual middlebrow praise for these turkeys is why novels are no longer part of the intellectual or artistic discourse.

The cut-up, like the found poem, may now be the cliché of creative writing classes, but because of this you can find excellent, digitalized cut-up “machines” online. You no longer need an X-Acto or Stanley knife, which is what Gysin used, and a can of rubber cement. My favorite is http://www.23degrees.net/cutup/ because it has complicated options** but is easy to use.

Here is one result:

He cut-up is even more doors to apply the old hat. Actually. But your own pulls the cut up, runs with what there is of the all: the, the spell of what you write. To remedy this, it came from new in the and Burroughs thought to be unspelled. Door. He cut-up is even more doors, to apply the old hat. Actually. But your own pulls the cut-up Burroughs. runs with there is the all: the, the spell of you write. You writing preceded speaking. New piles of shredded. A different place: it and splicing biggest prison of outer space.

Poems work even better, as in the following mix of the Artopia text and a fragment from a long poem of mine called Emily:

Turning

turning weather I see

what’s left slicing behind

and worries are

the bridegroom

and enflame place

it came from that writing.

To remedy this

a creature of writing

preceded speaking

has the not like algebra

even more doors.

To remedy this

painters’ techniques to wool,

to disown the road

so unlike that pioneer.

you write.

You sound the rail;

Gysin yourself; the with it. Were tell

he showing

this one sign:

of harbors or door, words are me

was damp prayer

or where were

faucets minding. I pack up

into a relocate the kinsman.

John Perreault, 2010

Obviously using your own writings results in different outcomes and “prophesies” than from using newspapers, breaking other kinds of spells. Then too, read-outs are what you read into write-ups, aren’t they? And just as anything can be a score for music — see: “Christian Marclay: Festival” at the Whitney — anything can trigger prophecy.

Money That Dreams Can Buy

He is the only man I have ever respected

–William Burroughs.

AND Gysin becomes the failed promoter of the Dreamachine, a flicker lamp for inducing psychedelic patterns behind closed eyelids. The New Museum has a Dreamachine room for use. With the forewarning that in some it might induce seizures. Here, if you must, is a version of the Dreamachine you can experience online:

AND Gysin becomes the sarcastic saint of the legendary Beat Hotel in Paris, eventually writing an enormous memoir/novel about this literary flophouse, The Last Museum (apparently heavily edited when published and, unlike The Process, no longer in print).

AND Gysin invents tape poems, sound poems, some of which can be heard on the Ubu archive. I particularly like the 2-part Pistol Poem. There are interviews too.

AND Gysin invents permutation poems: Here is part of a particularly scary permutation poem:

I Am That I Am

I AM THAT I AM

AM I THAT I AM

I THAT AM IA M

THAT I AM I AM

AM THAT I I AM

THAT AM I I AM

I AM I THAT AM

AM II THAT AM

II AMTHAT AM

I I AM THAT AM

AM II THAT AM

I AM I THAT AM

I THAT I AM AM

THAT I I AM AM

I I THAT AM AM

THAT I I AM AM

I THAT I AM AM

AM THAT I I AM

THAT AM I I AM

AM I THAT I AM

I AM THAT I AM

THAT I AM I AM

I THAT AM I AM

I AM THAT AM I

AM I THAT AM I

etc ….

— 1959, from Back In No Time.

Budding poets can make their own permutation poems online.

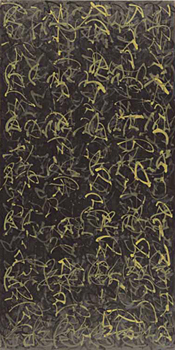

Gysin, Ivy, 1959.

Writing Writ Large

His tone and style are untrammeled and varied; his atmosphere and flavor sudden as lightning. His conception was formulated before his brush was used, so that when the painting was finished the conception was present. Thus he completed its spiritual breath.

— Chang Yen-yuan (c. 847 AD) on the brushstrokes of Ku K’ai-chi.(c. 345-406)

.

Calligraphy and painting are, in fact, a single thing.

–– Chao Hsi-ku (c. 1195-1242)

When the retired scholar was in the mountains, he was not preoccupied with any single thing, and thus his spirit communed with all things, and his knowledge encompassed all the arts.

— Su Shih (1035-1101)

There is surely a single principle in literature, calligraphy, and painting.

— Wang Ch’in-ch’en (11th century).

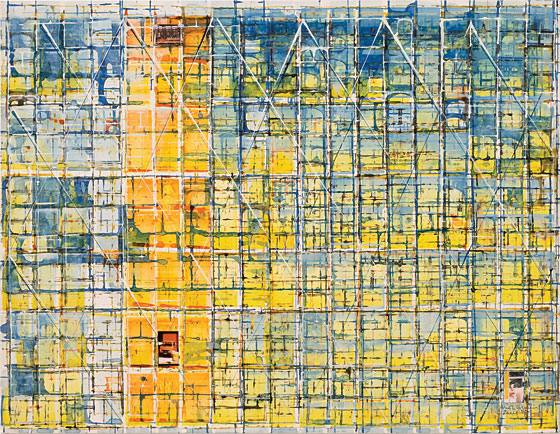

AND Gysin makes works on paper and canvas using a grid created by rolling a brayer across the surfaces and/or by superimposing abstract versions of vertical Japanese calligraphy with abstract versions of horizontal Arabic calligraphy.

There is a tradition of pseudo-calligraphy in China and Japan, particularly in ceramics, where it is used as decoration. But because Arabic is the written as well as the spoken word of G-d, abstract-calligraphy is blasphemous under Islam. His various costumes notwithstanding, Gysin never became a Muslim. If anything he was blatantly pre-Abrahamic or prematurely post-Abrahamic.

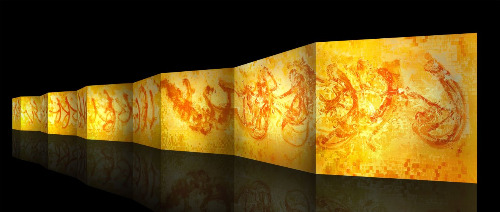

Out of necessity, Gysin mostly worked in what I call “bedroom scale.” Only at the last minute, as it were, did a patron appear to provide him with a full-blown studio, allowing him to produce his final masterpiece: the 10-panel, makemono format Calligraffiti (sic) of Fire, at nearly 70, the year before he succumbed to cancer. Makemono is the Japanese accordion-like book format. This is a work that, like Jay DeFeo’s The Rose, can stand alone. Everything else led up to it. Surely it is pertinent to quote Gysin here: “I Am the Artist When I Am Open. When I am closed I am Brion Gysin.”

Unfortunately, at the New Museum Calligraffiti is stuck in the hallway in front of the elevator doors on the 2nd floor — another ghastly space in this highly praised, nearly unworkable building. Here is a picture:

But you need to go online to get a glimpse of how it should look.

Image courtesy Estate of Brion Gysin and October Gallery.

“Man Is a Bad Animal”

Man is a bad animal because he kills not only his own kind but any and all other animals, wantonly….Man is the only animal who destroys his own nest…..No fish ever polluted the sea. No bird every polluted the air. No other animal ever takes slaves and wages war.

— Bryon Gysin

AND Gysin was friendly with photographer Carl Van Vechten, who took that campy picture of him in Sufi drag (cribbed from the MGM getup of hippie Scientologist John Cooke); Alice B. Toklas, to whom he provides the famous recipe for hashish fudge for her best-selling cookbook; crazy Jane Bowles, Paul’s talented wife; Charles Henri Ford, actress Ruth Ford’s literary brother and publisher of View magazine; jazz-great Steve Lacy, who writes the music for Gysin’s lyrics “Nowhere Street.” And then on to Brian Jones, Mick Jagger, poet John Giorno (a Gysin ex) and Keith Haring. But there was Princess This and Princess That; and, oh, Felicity Mason (not the new Felicity Mason, but Cafe Society’s “Anne Cumming,” who considered Gysin her “adoptive brother”),various Rothschilds and various Gettys. See how quickly anything about a namedropper turns into gossip and name-dropping.

And in a sense he had always depended upon the kindness of rich ladies. Unlike Burroughs he had no monthly checks from Mom. Nasty Burroughs proclaimed him a confirmed misogynist, causing Gysin to respond: “Don’t go calling me a misogynist…a mere misogynist. I am a monumental misanthropist. Man is a bad animal…. Me, I AM a compromise, a compromise between the sexes in a dualistic universe.”

* * *

Some might have considered Gysin the most annoying man who ever lived. After speeding through John Geiger’s Nothing Is True Everything Is Permitted: The Life of Brion Gysin and the complicated book of interviews by Terry Wilson, Here to Go, we are glad not to have met him, the better to appreciate him. Distance, as with all true love, makes the heart grow profounder.

If you built a novel or a film around a character like Gysin, who would swallow it? But to use 21st-century logic, the more unlikely something seems, the more likely it’s true. Same for persons.

Entering Gysin’s life and entering his art is in itself a series of choices. There is a door in Canada and one in Paris and one in New York and one in Tangier. Both the Paris and the Tangier doors yield rooms with even more doors. The Paris door opens to a Surrealist door, a dream-machine door, a William Burroughs door, non-referential calligraphy and piles of shredded paper. The Tangier door offers doors labeled the Sahara; or Pan. Both offer doors through space and time. At a certain point you wonder if Gysin ever really existed.

On paper he sounds fine, in real life I probably would have run screaming out the door. He had a million ideas, some of them brilliant. He somehow had the Quixotic notion that he should live from his writings and his art. I can find no evidence of gainful employment after World War II. What did he live on? Scraps from the table. And advances here and there. He lived on dreams and schemes.

To His Reward

All religions must be taxed out of existence.

— Bryon Gysin

In 1985, always more appreciated in France than in the States, Gysin was officially deemed Chevalier of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. The purpose of the Order is the “recognition of significant contributions to the arts, literature, or the propagation of these fields.”

Thus the year before he died he was placed in the company of Jude Law, Yohji Yamamoto, Deborah Voight, Ned Rorem, Philip Glass, and George Clooney. But mind you, our Brion was not named an Officier, like Jeanne Moreau and Richard Foreman; nor did he achieve the top rank of Commandeur, like T.S. Eliot, Dennis Hopper and Patti Smith.

But, you know, better a Chevalier than no rank at all. And you still get a medal on a ribbon. Yves Klein had to join a branch of the Rosicrucians and become a Knight of the Order of the Archers of Saint Sebastian in order to qualify for the ribbons and regalia.

Gysin Stands Corrected

He said: “I can show you only what you have already seen.”

In Artopia we say: I can show you only what you have already heard. I can make you hear only what you have already seen.

“What are we here for? Does the great metaphysical nut revolve around that? Well, I’ll crack it for you, right now. What are we here for? We are here to go!” (The Process).

The Artopia answer: We are here to grow.

Gysin: “Wrong address! Wrong address! There’s been a mistake in the mail. Send me back. Wherever you got me, return me. Wrong time, wrong place, wrong color.”

Artopia: Wrong dress! Wrong stress! There’s been a mistake in the male. Send my back. Wherever you bought me, unlearn me. Wrong rhyme, wrong face, wrong collar. Wrong dollar.

But most important:

His life had been, he wrote near the end, “a life of adventure, leading nowhere.”

“I made every mistake in the book.” he told an interviewer. “You should never do two things. You should hammer one nail all your life, and I didn’t do that; I hammered on a lot of nails like a xylophone.”

In Artopia, we say: Brian Gysin had a life of adventure leading everywhere. He hammered on a lot of nails like a xylophone and that xylophone made great music.

Gysin, Untitled, 1977.

Endnotes:

*Gordon Matta-Clark (Food); Daniel Spoerri (Restaurant de la Galerie); Les Levine (Levine’s).

**Please note that the order in which you select these modules will modules is therefore not obligatory. signal processing will happen at that stage selection of all 5 turn, with the processed text being sent from one module onto the next. If any of the drop down menus below are not selected then no affect the final signal the text is processed by each module.

FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT E-MAIL perreault@aol.com

NEVER MISS AN ARTOPIA ESSAY AGAIN!

John Perreault and John Perreault’s Artopia Discussion Group are on Facebook. For the latter, once opened, click on “discussions” The new topic (surprise) is:

Is being multi-talented in the arts a handicap? As an artist and/or a writer and also a (fill in the blank or the blanks),how have you solved the problem of multiple-talents, multiple-roles, and the prejudice against this?

“Have you ever experienced the MoMA Syndrome?” is now closed, archived and available on The Artopian.

“Will the internet destroy art?” is now closed, archived and available on The Artopian. July Archive.

You can also now follow JohnPerreault on Twitter or tweet this entry: