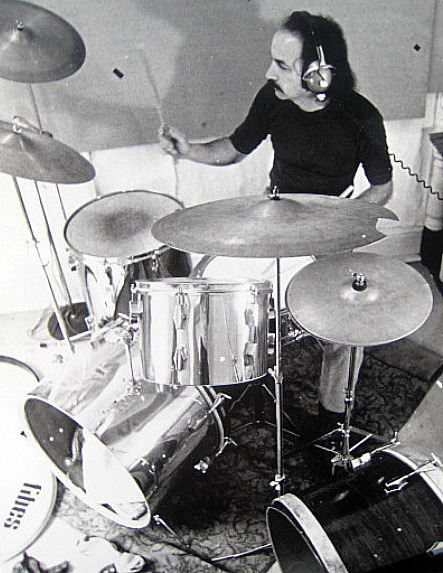

Rafael Ferrer playing drums, Philadelphia, 1967

A Life Divided?

The work of Rafael Ferrer is characterized by a caesura, or so it might appear. Provocative classics of the late ’60s and through most of the ’70s — installations with a definite guerrilla flavor, using dead leaves, ice, grease, cloth, galvanized steel, and so forth — are perceived as distinct from the tropical paintings that followed. It would seem that the former celebrates the cerebral and the ad hoc, whereas the latter are densely representational paintings that play more directly with heritages and languages. Or are the paintings Neo-Expressionism-cum-Hairy Who? Later we find out that the suave representations of Alex Katz, limning the quotidian and the New York School of poets and painters, have played their part, too.

Trying to account for Ferrer’s sculptures makes classification even more difficult. The hanging “kayaks” introduce anti-tropical fantasies and reversals of European Romanticism. What is the mirror to the Euro-American escapism, which, from Melville to Gauguin, involved the tropics? Why do I, who have been to Tahiti, still think of South Pacific humidity as preferable to the identical climate we now suffer through on the streets of Mannahatta or in the former potato fields of Long Island now encumbered by empty mansions? If you yourself are tropical — let’s say of Caribbean origin or, nowadays, a New Yorker in July — might not the arctic be your paradise? Might not kayaks be exotic? And, come to think of it, wouldn’t great blocks of melting ice be nice?

In a period characterized by a reevaluation of the performative art of the ’60s and ’70s, the danger now is that all subsequent paintings, not just Ferrer’s, will be seen as retardaire. In fact, compared to his earlier installations, Ferrer’s works on canvas are not in the least bit sexy. A reconceptualization is required. Although it focuses on the paintings, “Retro/Active: The Work of Rafael Ferrer” at El Museo del Barrio (to Aug. 22) is a long-delayed and long-required toast to one of our most talented mavericks.

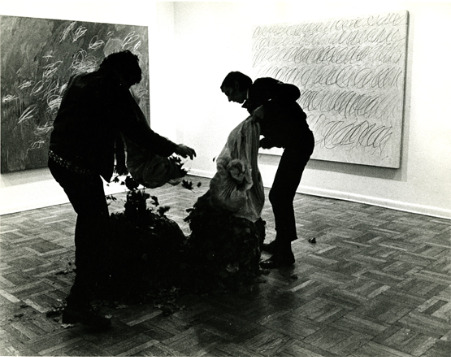

Ferrer, Three Leaf Pieces, 1968 (Castelli Gallery)

Or A Double Life?

In 1968, Ferrer, uninvited, dumped piles of dead leaves into the elevators of the then important Dwan and Fischbach Galleries, in the front room of Castelli further uptown and at the Castelli Warehouse, where Robert Morris had installed his anti-form show.

The following year, when Ferrer was invited by Whitney curators Marcia Tucker and James Monte to participate in “Anti-Illusion: Procedures/Materials,” he deposited leaves and blocks of ice on the entrance ramp of the museum. Inside, he created a wall/floor piece involving grease and hay. Some of the flung hay clung to the greased-up wall.

In 1970, sitting in a fountain in front of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Ferrer performed Deflected fountain, for Marcel Duchamp.

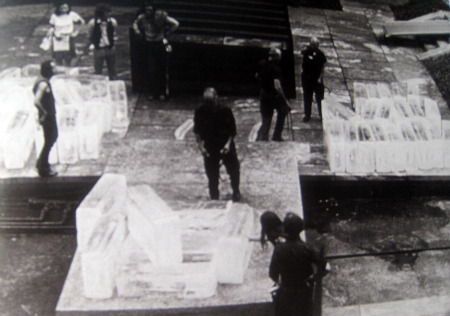

The same year, for the exhibition “Information,” he displayed 50 blocks of ice in MoMA’s garden.

* * *

* * *

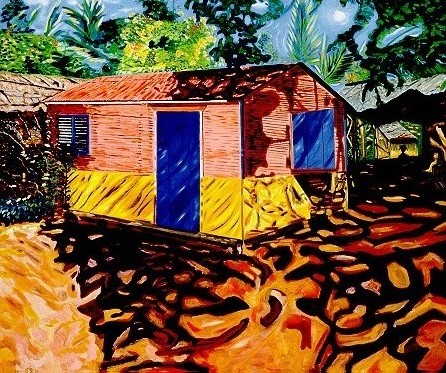

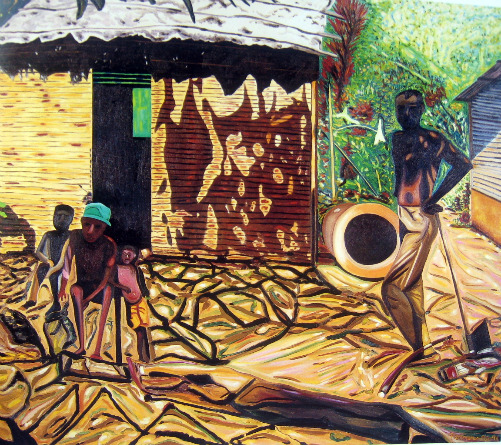

Nevertheless, by 1980, Ferrer was making paintings of Caribbean shacks, outdoor cookery, cockfights, hallucinatory deep-noon shadows. These are featured in the current exhibition at El Museo del Barrio, the performative works reduced to a room of ephemera.

Ferrer, El Sol Asombra (The Sun in Shadow/The Sun Astounded), 1989.

Born in Puerto Rico, bilingual and bicultural, Ferrer as a young man worked as an Afro-Cuban drummer in New York. Because his beloved stepbrother was the actor José Ferrer, he also met various Hollywood types. He definitely did not “come from the slums of Puerto Rico,” as one reviewer put it in1971. This error is cited and corrected in exhibition curator Deborah Cullen’s catalog essay “Poetry on the Margins.” In Vincent’s Katz catalog interview the artist himself says he drew up in {miramar, a well-to-do neighborhood of San Juan.”

Why would someone make that kind of mistake in an otherwise fine exercise in appreciation? It is more romantic, I suppose, to come from the slums than from more aflluent climes. Well, just ask anyone who has crawled his way out of the slums how romantic that is. The awful prejudice here is the notion that all Puerto Ricans come from the slums. Or all Cubans. Or all Mexicans.

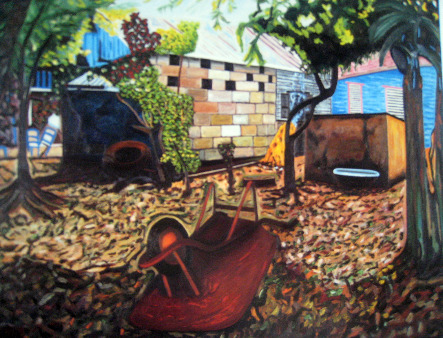

Ferrer: Paraiso (La Barbacoa), 1994

Another Day, Another Caesura

Herewith, I can further develop my theme of Second Acts in art. Constant readers will recognize that my braided view of art is slowly but surely being expressed by Artopia itself. Cross-referencing among the posts is only the most obvious form of braiding. Thematic strands are coming to the fore.

The surprise of my recent weigh-in on late Warhol was that the Pop Pope indeed did have a Second Act. His First Act ended with the assassination attempt. His Second, following the caesura of the dreadful commissioned portraits, consisted of picking up where he had left off. Under cover of his media bliss, he plugged new images into his working procedure, his style. Some worked: the Rorschachs and the Last Suppers, in particular. Ferrer’s Second Act, as described above, was a little different, as was his caesura.

My idea is that Ferrer is having a Third Act. Here, my model is the foolproof template of a traditional play. First Act: characters and basic situation introduced; End of Second Act, characters are up a tree; Third Act, characters get down from tree — problem solved.

The Ferrer Third Act is the notion that there is in fact no division between Ferrer’s anti-form works and the paintings that followed. The current exhibition, if it were not so soft in this regard, could have proved this.

Carter Ratcliff’s smart and well-written catalog essay is a reprint of his 1983 Cincinnati Contemporary Art Center piece, “Rafael Ferrer in the Tropical Sublime,” composed closer to the break-off point. He hints at an unacknowledged continuity, but backs off. Leaves are romantic. Yes and no.

I am not convinced that the performative works were in themselves a criticism of post-Minimal anti-form. But Ratcliff is right about the ice and the kayaks having a different meaning for someone born in the Caribbean than for someone born up north.

In the catalog, Edward Sullivan dutifully delineates the Caribbean and Euro-Caribbean antecedents of Ferrer’s early work and his post-1980 turn. That Ferrer once met Wifredo Lam is probably important, but is it more important than that his sister-in-law was Rosemary Clooney? We have Show Biz connections confirmed in a long e-mail interview conducted by Vincent Katz, son of Ferrer’s friend Alex, wherein Ferrer also gives a lot of credit to the emotional support of his brotherJosé.

Oddly, critic/poet Ratcliff wonders why Philip Leider (editor of Artforum, 1962-71), when reviewing the Castelli anti-form show for the New York Times in 1968, was blind to Ferrer’s leaf pieces. He had to step over them to see the exhibition, but he did not mention them. It were as if they were invisible, and Ratcliff suggests that this was because Ferrer was challenging the anti-romanticism of Minimalism, a dictum subscribed to by Leider. But something far worse was involved.

Even mentioning Ferrer’s leaves would sanction similar actions in the future, thus threatening curatorial and art-dealer power. Control over who gets shown is essential. You can’t just have someone walking off the street and dumping bushels of leaves on the floor, can you?

Currently, this may be why Thierry Geoffroy, the creator of Critical Runs, Emergency Rooms, and Penetrations, is not yet well-known. Artists running through the streets and artist complaining-rooms may be strange, but inserting unsolicited artworks in actual exhibitions (i.e., Penetrations) is truly destabilizing.

More productive is Ratcliff’s valorizing of Ferrer’s surprising but possibly ironic fondness for conquistador Hernán Cortés, who, when he wanted his men to march to the interior of Mexico to challenge Montezuma, sank all boats so they couldn’t turn around and go back to Cuba. When asked what he would do next, Cortez reportedly answered: “Something will turn up.” The implication is that Ferrer, when he turned his back on anti-form, had burned all boats. However….

Diego Rivera, The Conquest and Arrival of Cortés..

Rafael Ferrer, The Third

A number of image juxtapositions throughout the El Museo del Barrio catalog make a case for previously unnoted continuities: A 1969 installation (Niche) is paired with The Barbecue of 1991-92. The galvanized steel and the tarp in the installation seem to rhyme with the materials depicted in the painting, as does the sense of enclosure and of light. Disorder has no border.

Hanging elements in For Reba Stewart, 1971 (Philadelphia ICA) rhyme with the hanging carcass in the 1987 painting Innocence. A pile of leaves from Three Leaf Pieces (1968) rhymes with the leaves in Paradise/Barbecue (1994). The rectangular opening in the tent in Tent, Tree, Bucket, Light (1970) rhymes with the window seen through the door of The Open Door (1987). The whirlwind of hay in Hay, Grease, Steel (1968) rhymes with the hubbub of black shadows in The Sun in Shadow/The Sun Astounds (1989).

Ferrer, Inocancia/Innocence, 1987

Ferrer: For Reba Steward, 1971

These “rhymes” expose the previously unnoted inspiration for Ferrer’s anti-form installations. Both the installations and the paintings spring from a common ground, a common landscape. If the photos of the anti-form pieces were similarly juxtaposed with the paintings in the installation itself, a good case for continuity might be made. Shouldn’t curator Cullen have at least re-presented a leaf piece? Or stuck some ice blocks at the entrance to the museum?

Here instead, the message reads that the errant son of Puerto Rico turned his back on Yankee art and returned to his Caribbean roots. The rich and lush is to be privileged over the cold and rational, never mind that on both sides of the Ferrer caesura we are always facing chaos.

Ferrer: Conquista de la Solidad/ Conquering Solitude, 1990-91

Themes To Die FromThe work in the exhibition is not displayed chronologically. Instead there are clusters under confusing double-headed titles: “Darkness/Menace,” “Art/Memory,” “Series/Language,” “Music/Rhythm,” “Light/Movement.” Almost anything could fit anywhere. There are large paintings and less consequential “faces.” We are treated to some complicated hanging “kayaks” but are also force-fed some pre-Conceptual welded things that could have easily been omitted.

I found, by the way, that I particularly liked the larger paintings. There is no doubt that The Barbeque, Innocence, Paradise, In the Mountains…, and Conquering Solitude are strange and wonderful. And then there’s the collection of paper-bag self-portraits and the poetic, painted blackboards. I was drawn to both, perhaps because they are slightly mad accumulations, but also because they embody a fountain of creativity, improvisation, inspiration continually renewed.

I suppose the “themes” are an attempt to make sense of Ferrer’s tendency to jump back and forth and all over the place. I would rather have had the rhythm or the polyrhythm or the braid of his oeuvre as it developed. The themes stand in the way. If you are trying to get the cat back into the bag to rescue it from the oncoming flood, the easiest way may be to kill it first, but that is of no use to the cat.

Another theme, although it is not posted as such on the walls, is cultural identity. In her catalog essay, Cullen mentions that the ultra-decorative, more-is-more artist Lucas Samaras once told Ferrer to put “more Puerto Rico into it”; whereas Minimalist Morris insisted, “I don’t want to see you concerned with being a Puerto Rican.” Unfortunately, neither artist was right. I like it best when Ferrer’s imagination takes command.

Ferrer: La Barbacoa (The Barbeque), 1991-92

Pull Out the Rug!

By 1980, there was indeed a sense that Conceptual art, Minimalism and the various post-Minimalisms had gone as far as possible. A nostalgia for expression and emotion raged. Even the flamboyant was fresh. I thought Patterning and Decoration would be the answer. It was gridded, so it could claim a distinguished history. It was global, cross-class, and cross-cultural. But Neo-Expressionism won, also beating down what we now are forced to call the Pictures Generation. Yet only temporarily.

I am not sure even now that Ferrer is an expressionist. But who is? You can’t step into the same paint twice. You can’t be sincere while looking in a rearview mirror. Wasn’t Neo-Expressionism really a kind of Conceptual Expressionism? Don’t look behind, abandon all ships; something will turn up.

FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT WHEN A NEW ESSAY IS POSTED, PLEASE CONTACT: perreault@aol.com

John Perreault is on Facebook. You can also now follow JohnPerreault on Twitter

From the Artopia Discussion Group: “Will the internet destroy art?” is now archived and available on The Artopian.

.