Jailbreak

I was recently in Philadelphia to check out some site-specific artworks curated by yours truly. They were part of that city’s Clay Studio “Interactions” project, tied to this year’s NCECA, the National Conference for Education on the Ceramic Arts.

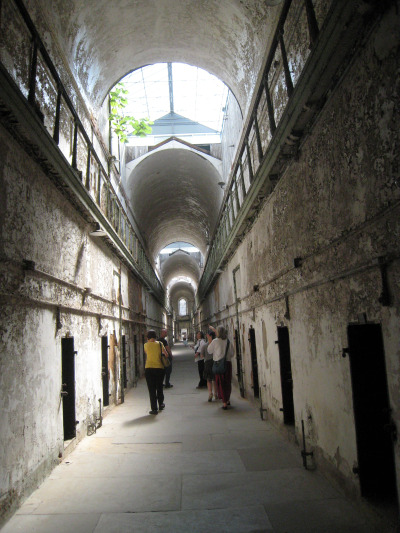

Checked in at my Market Street hotel and immediately took a taxi to historic Eastern State Penitentiary. Here are a number of virtual tours on their website.

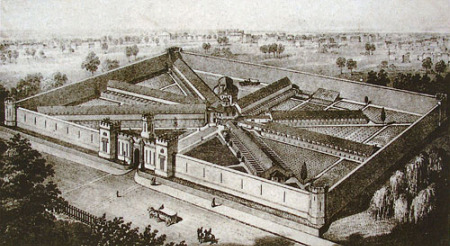

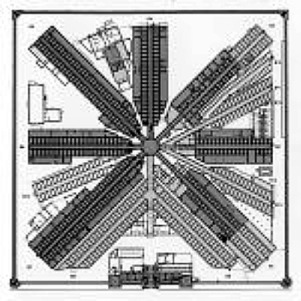

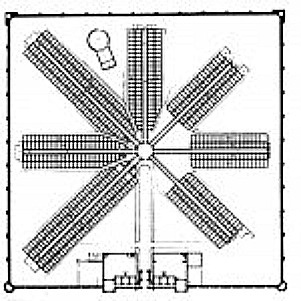

Enclosed by intentionally foreboding, fortresslike walls, this seven-armed star-of-penitence, opened in1829, grew by accrual or cellblock-implant over the years, until there were 15 arms or spikes of darkness radiating from the octagonal center, crowned by a surveillance tower.

Shut down in 1971, the ESP made the World Monument Fund’s list of 100 most endangered sites and was eventually deemed a National Historic Landmark. This was not because British-born John Haviland (1792-1892), now associated with New World Neoclassicism, was such a great architect. In fact, he never really got his penitentiary commission quite right, and it grew organically as it was being built. Need more cells? Just add a second story and forget the tiny – and individual — walled exercise-yards. To be fair, nothing on this scale of terror had been attempted before.

Eastern State is now a stabilized ruin open to the public, with educational tours and temporary art exhibits throughout. By the way, cost-effective stabilization rather than restoration allows us to see a building embedded in time, not as an abstraction created by reduction to a judicious but artificial date. Buildings are like people. At what age would you be the personification of the “real” you?

The crime tomb looms over Philadelphia’s Cherry Hill in the Fairmount District. Although not precisely a panopticon, it’s a monument that Michel Foucault would have loved.

Can we think of prisons without being imprisoned by the metaphors created by everyone’s favorite penologist? Foucault’s writings are like looking through the Vaseline-coated window of a slowly moving train. If you think that the problem is bad French-to-English translation — and/or you need a Foucault jailhouse refresher – click here for the prince of palaver in English!

Foucault’s Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, although peppered with insights, is the evil template for gradspeak:

The panoptic modality of power–at the elementary, technical, merely physical level at which it is situated–is not under the immediate dependence or a direct extension of the great juridico-political structures of society; it is nonetheless not absolutely independent. Historically, the process by which the bourgeoisie became, in the course of the eighteenth century, the politically dominant class was masked by the establishment of an explicit, coded, and formally egalitarian juridical framework, made possible by the organization of a parliamentary, representative regime.

The first part of the initial compound sentence here is clearly, simply wrong — so wrong that the reversal in the second part is nonsensical. One, therefore, distrusts the second sentence. In addition, it is difficult to see how a representative government and a – I guess, he means to say – democratic judiciary could have masked the bourgeoisie society that it expressed and that had created it.

You see that even outside attempts at explanation create further muddles.

Michel Foucault (1916-1984), c. 1965?

Nevertheless, Foucault’s mere mention of Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon proposal (1787) turned the concept into an emblem of postmodern life. The cells in Bentham’s British prison were to be so arranged that the isolated inhabitants could be watched at all times from a central point of surveillance.

Practical Bentham asserted that as long as the prisoners thought they were watched, observers did not always have to be present, thus saving salaries. Cost-effectiveness was Bentham’s main point, not torture or reform. The budgetary genesis of the panopticon seems to have eluded our French philosopher — nor does Foucault bother much with the horrors of requisite, and absolute, solitary confinement.

Practical Bentham asserted that as long as the prisoners thought they were watched, observers did not always have to be present, thus saving salaries. Cost-effectiveness was Bentham’s main point, not torture or reform. The budgetary genesis of the panopticon seems to have eluded our French philosopher — nor does Foucault bother much with the horrors of requisite, and absolute, solitary confinement.

The brutal presence of the ESP will see to that.

Sensory deprivation. Social engineering. Mind control.

Unlike Bentham’s beehive, the ESP arrangement of cells is not circular. It is worse. Often referred to as the hub-and-spokes, wagon-wheel design (cribbed from English asylums for the insane), the Philadelphia star-of-doom was widely imitated. Unlike Bentham’s roundhouse, the structure is easy to imagine. Once glimpsed, the surveillance hub of this wheel of misfortune is always in your mind — a figment of your imagination more real than the tower itself. A diagram that sticks in your head can henceforth determine perception.

Because Eastern State Penitentiary in its earliest years was an attempt to create total solitary confinement, it can now be seen as the temple of social deprivation. On the theory that criminals would not want to be recognized in or out of jail, you were forced to wear masks when others, even guards, were present (until 1903).

![hooded inmate].jpg](http://www.artsjournal.com/artopia/hooded%20inmate%5D.jpg)

You were known only by a number, not a name. There was a reason. If you were number 34888, that meant you were the 34,888th sinner to be admitted to hell. Silence was leaden, and imposed.

Originally, food was delivered on a cart with leather-covered wheels, so the silence would not be disturbed.

Keeping in touch was made totally impossible. How can you love a number? How can you plot escape? How can you exchange information with someone hidden inside an eyeless hood, closed at the neck by a drawstring?

Although central heating and flushing toilets were necessary innovations, the main engineering problem was how to keep the jailbirds from communicating with each other by rapping on empty pipes or sending messages via plumbing. Toilets were automatically flushed, first by even- then by odd-numbered cells. I cannot imagine how.

The theory behind this form of control was that the Pennsylvanina plan was better than public torture or the prevailing Bedlamlike conditions of other prisons — so claimed the Quaker businessmen who deverloped the new and improved system.

In the early years, the only book permitted was the Bible; the only public debate was whether or not the isolated inmates would be permitted to work in their cells, thus distracting them from dwelling on their sins. No one questioned the reign of silence.

When I first described the Eastern State, perhaps in too much detail, to a friend who had been born and bred in Pennsylvania and always assumed the Quakers were the good guys, she broke into tears.

Numbering Systems

I had visited Eastern State several times before, once to perform a guerrilla circumambulation.

Now I was focused on finding the site-specific works I had facilitate under the Interactions rubric.

Disoriented by the signage and the exhibition handout map, I consulted a charming young guard — far different form the original guards, no doubt.

“Oh,” he said, “it is confusing. But the numbering of the cellblocks is historical, and we honor that.”

He explained that the cellblocks were not numbered consecutively, but according to when they were built. The original “one through seven” were as orderly as a backwards clock-face, beginning with Cellblock One to the right of the entrance. But then eight more cellblocks were added over time, interspersed with the original radiating wings.

The numbering of the cellblocks, beginning at #9 at 23 minutes after noon, running counterclockwise, remains #9, #1, #10, #13, #2, #15, #11 (Death Row), #14 (Operating Room), #3 (Hospital), #4, #5 (Dining Halls), #6, #12, #7 (Synagogue!), and #8 (Al Capone’s cell).

I wondered if the layering of numbers was a particularly Philadelphia thing, because earlier I had noticed that the city’s main railroad station entails a related bit of Dada.

Like Eastern State Penitentiary, 30th Street Station has preserved its own historic numbering system. Stairway numbers are permanently embedded in the walls, but then below are the added and unrelated track numbers, two to a stairway, and finally, superimposed most recently, are the Amtrak gate numbers, also incongruent. This means that arrival and departure announcements must include all three numbering systems. For instance, your train to Pittsburgh might be leaving at Gate Three, Stairway Five, on Track 12 .Wouldn’t a single, prominently placed gate number be enough? Not in historic Philadelphia.

Or is it insane homage to the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s incredible Duchamp collection? Not necessarily.

I finally remembered that in Tokyo, street numbers, like those for the ESP cellblocks, are not consecutive but assigned according to when the houses were built. As one guide writes:

Finding a block inside a district is often very difficult. You have to wander between the blocks looking at the block number panels until you find it. Your task is easier when the map indicates the block numbers. But very often, outside central Tokyo, the map will only indicate the district name, and you’ll have to find the block yourself. Or your map may be outdated……Inside the block, the houses are numbered according to when they were built, not to where they are located in the block. House number #32 will probably not stand by house number #33 or #34. You may have to turn around the whole block before you find it.

How Many Americans Are Now in Prison?

The U.S. prison population, or as the Department of Justice would have it, the “correctional” or “custody” population, has been increasing more than the increase in population: 1,842,00 in 1980, 7,308,200 in 2005. Are people committing more crimes? Has enforcement improved? Have the courts become tougher?

And if you think you know how the prison population looks, think again. According to the Federal Bureau of Prisons, most prisoners are, yes, male (93.4%); more than half are “white” (57.6%); the average age is 38. Not 18.

According to the Prison Policy Initiative, prisoners are also political pawns:

In New York State, for example, one out of every three people who moved to upstate New York in the 1990s actually “moved” into a newly constructed prison. The State bars people in prison from voting, but their presence in the Census boosts the population of the upstate districts whose legislators favor prison expansion. Without this phantom population, 7 upstate New York State Senate districts would not meet minimum population requirements and would have to be redrawn.

So….

Let’s All Get Together

Two of my nominees for “Ceramic Interactions” made it through all the hoops: Judy Moonelis and Jeffrey Mongrain. The idea of asking artists to create works in response to art in Philadelphia collections and/or particular sites was mine. The artists could choose their sites. I had my fingers crossed that “my” artists would choose my favorite place in Philadelphia, and they did.

Two of my nominees opted for ESP.

Here are all the Interactions artists at ESP, on view until November.

Here are the ESP-commissioned artists also on view. Of these, Artopia-approved fimmaker Bill Morrison has altered found-footatge of the crowds assembled to greet the release of Al Capone.

So, artists out there, which would you have chosen, the stabilized ruin of an historic prison or the sleepy, sleepy Philadelphia Prison — oh, I mean Museum — of Art?

In the case of the PMA — and another institution that behaved so badly it shall be forever nameless — curators or higher-ups rejected some of our artists and, of course, in general resisted having new artworks placed in or near sacrosanct displays, even if only for a brief period.

That was not the case when I used the same idea a few years back for a G.A.S. (Glass Art Society) conference I was hosting back in Brooklyn, commissioning artists to make pieces in glass in response to works in the Brooklyn Museum

Of course, our glass conference only had 2000 attendees, as opposed to this year’s NCECA conference in the City of Brotherly Love, with over 3000 clayaholics. As I should have predicted, few bothered to look at or could have had time for the 98 special ceramics exhibitions in the Philadelphia area. There were friendships to bolster, jobs to pursue.

Well, any excuse for an art project is a good excuse.

An uninformed reader might wonder why both glass and clay artists have professional organizations and national gatherings each year, as do jewelers and metal workers of all kinds — including blacksmiths. Turners congregate too, as do furniture makers and fiber artists. All such shindigs feature a keynote address, lectures, panels, demonstrations, and exhibitions.

Is this true only of craft art? No, sculptors have a confab. The real question is why painters don’t congregate. Well, you know why. They are at the top of the heap and don’t have to meet. Plus there are no trade secrets to trade or techniques to bone up on; no marketing tips are needed, either. Paintings sell like hotcakes. Or used to. Will the forthcoming economic rebound spur an art-market return?

Sir John Daugman and Charles Dickens

How do you “curate” site-specific artworks?

I wanted nominees and participant artists who had demonstrated they could work with historic structures and had already tackled the site-specific mode.

Jeffrey Mongrain, known to me for his sculptures placed in cathedrals such as St. John the Divine in New York, here has offered up The Iris of Sir John Daugman. In a break from his minimalist output, Mongrain connects the tracery of the “ocular” window in Cell # 9 in Cell Block 2 — and thus all the windows in the cells — to the framing of the clock in the tower of Philadelphia City Hall. In his ceramic tracery he implanted a photo blowup of the left iris of Sir John Daugman, who the handout identifies as “the inventor of the iris-scanning technology used for security identification at international airports.” One can see the iris skylight through an angled mirror below.

On the basis of her site-specific sculpture for the historic Kehila Kedosha Janina Synagogue in New York’s Chinatown, I knew that Judy Moonelis — another artist I have followed over the years — would be perfect for the project, particularly if she choose ESP as her site, which she did.

She began by investigating the history of women inmates incarcerated at the penitentiary from 1831-1923. The space she choose had been the laundry, where many of the women had been allowed to work. In Blood Cell, the forms that stretch out on the rubble-strewn floor are based on the human circulatory system and its capillary beds, rhyming with the roots, branches and moss that have invaded the space.

Moonelis’ Brain Cell was inspired by Charles Dickens, who visited Eastern State in 1842 and “perceived the invisible damage inflicted by the solitary confinement approach,” describing it as the “slow and daily tampering with the mysteries of the brain.” Moonelis’ hanging forms are imaginary models of the neural injury caused by isolation.

Was it an accident that both my candidates previously had made site-specific work for houses of worship? I don’t think so. Like churches and temples, ESP is public architecture, but turned inside-out.

Eastern State Penitentiary is a house of worship; its god is The State or The Law or The Demon of Public Order and Tranquility — the God of Silence.

He does not stare upon the air

Through a little roof of glass;

He does not pray with lips of clay

For his agony to pass;

Nor feel upon his shuddering cheekThe kiss of Caiaphas.

From Oscar Wilde: The Ballad of Reading Gaol

Geophagy in Philadelphia

Each of the curators selected by the Clay Studio for its “Interactions” project was also allowed a group-approved, but strictly personal, exhibition. Mine was HUNGER, Philadelphia by J.J. McCracken at the Painted Bride Art Center (to May 15).

Suffice it to say that McCracken also did not disappoint. I first saw her work in a group show I juried in Arkansas. The piece that struck my fancy was STASIS. A number of serious youngsters in white coats, after punching a time clock, threw perfect little vases that were then vacuum-sealed in plastic bags, labeled, priced ($22 per pound) and put on display.

The next major piece I became aware of was the 2008-09 Living Sculpture Project: clay-soaked young women “performed” a series of vignettes, such as playing a clay-coated cello, knitting while perched on spheres, trying to form perfect clay spheres with their fingertips, etc.

McCracken calls her large-scale artworks “active installations” rather than performances. They are allographic rather than autographic, in the analytical terminology of art theorist Nelson Goodman. Philosopher-critic Arthur Danto reminded me of this language key, in response to what I recently wrote about Marina Abramovic at MoMA. Goodman uses these terms to distinguish between music performances and the scores themselves. In Goodman’s view, only the latter can be forged.

My way of expressing this difference was to call my preferred examples of Performance Art charismatic, i.e. dependent upon the execution by the author/performer, leaving artists theater that does not require the artist himself/herself in an as yet unnamed category containing most Happenings, most Fluxus Events and, it now turns out, McCracken’s “active installations.”

In these audiences are allowed to come and go. Actions – directed but not performed by the artist — may leave behind installations then viewed without the “performers.”

I have since discovered, as her Philadelphia piece bears out, that McCracken also favors certain themes. The impossibility of preservation is one of her motifs. Her preferred medium is unfired clay. In some sense, she is deconstructing ceramics. Not only has she attempted to preserve unfired clay vases by vacuum-sealing them, she has also stored unfired clay objects in Mason jars filled with Karo syrup.

In HUNGER, McCracken addresses inner-city scarcity by exploring the theme of geophagy, or eating clay. Yes, people, mostly very poor people, eat clay, not only in the American South, but worldwide. Some swear it is a pregnant woman’s nostrum, supplying minerals otherwise unattainable, but it is also clearly a food of last resort.

On April 1 and 2, for two hours (“dinnertime”— from 6:30 to 8:30) the public could dip in and out of the Painted Bride (a well-known Philly performance venue) and watch slow-moving, clay-slip covered women occasionally break off small pieces of clay from a sumptuous banquet table of slip-cast, but unglazed and unfired, clay fruits and vegetables. They chew; they swallow. [Also May 7, 5-7 PM; closing ceremony May 15, 1 PM.]

Certain areas of North Philadelphia are functionally barren; those brownfields can be reclaimed for agriculture by the use of raised beds full of imported soil and proper compost. Philadelphia has the lowest ratio of supermarkets to population of any large city in the U.S.

Upstairs at the Painted Bride, a sampling of hydroponically grown vegetables holds sway, the entire live-plant array to be donated to the Stenton Family Manor homeless center, to inspire alternatives to the available food resources.

Certainly she [McCracken] is expanding ceramics by deconstructing ceramics. But her critique is not only media-specific, it is oddly poetic. Loss is not a popular topic, and accumulation and decay are not the usual ceramic themes. Her work turns loss into art’s gain.

John Perreault, “Let Them Eat Clay,” Hunger, Philadelphia/ J.J.

McCracken, The Clay Studio, Philadelphia 2010.

FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT CONTACT: perreault@aol.com