A Life That’s Picardesque

If you wrote a novel or a play or a jazz opera about Lil Picard (1899-1994), who would believe it? She would pop up in various places in the 20th century, wearing different wigs. Very Brechtian, with music by Kurt Weill. If there were a movie, who would star? She herself had a brief appearance in E.A. Dupont’s Variety (1925).

A cabaret performer during the Weimer Republic, she knew the Dadaists George Grosz, Hugo Ball, and Richard Heulsenbeck, who were antiestablishment and, unlike the Futurists, antiwar. When she became a journalist, her first article was “The Jazz of Life.” She finally left Nazi Germany in 1936.

In cabaret costume, Berlin, c. 1920

In New York during World War II, she became a milliner and proprietor of “De Lil” (est. 1939) and then of “The Custom Hat Box” (est. 1942) at Bloomingdale’s.

“Surrealist” hat by Picard, 1939

After meeting him by chance in a downtown art gallery in 1952, she began a 10-year relationship with mystical painter Alfred Jensen, who wouldn’t let her go to Provincetown or the Cedar Bar and didn’t want to share her with her husband — “He [Jensen] didn’t understand that I was a free spirit,” proclaimed Picard. Later she had an affair with painter Ad Reinhardt.

In the ’60s she wrote about art again — for the East Village Other, various German art publications, and Andy Warhol’s Interview. She played Andy’s mother in one of his films. She was wearing wigs way before he produced his self-portraits wearing his notorious fright wig.

In the exclusively online catalog for “Lil Picard and Counterculture New York” (at NYU’s Grey Art Gallery, to July 10) you can listen to two taped phone calls between Picard and Warhol, if you are interested in such. She is merely trying to arrange a meeting between Warhol and a German writer, but it is good to hear her voice.

Picard was an artist and writer. She was bicultural. After showing painted collages in various 10th Street galleries, years later she reappeared as a performance artist. She offered up her first “sociopolitical happening” in 1965 at the Café au Go Go in Greenwich Village, a basement venue for the likes of the Grateful Dead, Muddy Waters, and Lenny Bruce (who was arrested there for obscenity in 1964). Picard’s piece, The Bed, was “performed from an electric bed, assisted by the dancer Meredith Monk,” writes Kathleen Edwards, chief curator at the University of Iowa Museum of Art, in her online essay. “Punk” novelist Kathy Acker also helped Picard with another performance, Tasting and Spitting (1976). Lil knew everybody. For three decades she was even a friend of the novelist Patricia Highsmith.

Strangers on an Elevator

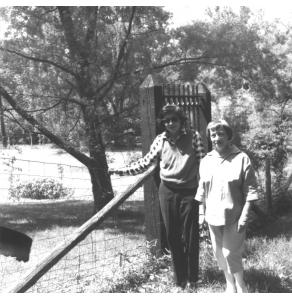

Photo: Picard and Highsmith, n.d.

According to biographer Joan Schenkar (The Talented Miss Highsmith: The Secret Life and Serious Art of Patricia Highsmith) Highsmith met Picard “in an elevator at a gay party in October 1947” [per Highsmith Diary, October 24, 1959.]. “Pat managed to suppress her desire to kiss Lil, but Lil’s position as an older married woman with a husband, whom she seems to keep secrets from” enchanted Pat, and she began to visit Lil everyday.”

For a 1975 publicity quote, Highsmith offered: “Lil Picard is fun. I have known her and her work for twenty-eight years and she is still fun. She is incapable of creating a boring drawing or painting.”

This is from the author of the twisted Strangers on a Train and the creator of the amoral Tom Ripley.

Highsmith dedicated Those Who Walk Away (1988) to Lil Picard, “one of my most inspiring friends,” even though they had stopped speaking in 1978 —because of political disagreements, opines Schenkar.

Through another index search, we discover that Highsmith, alas, admired Margaret Thatcher and voted for George Bush and then Ross Perot. The dates don’t add up. Why would Highsmith dedicate a book to someone she had not spoken to for ten years?

Note: Now wouldn’t it be interesting if someone published or if there were easy access to the 900 or so Picard/Jensen letters sitting there in the Archives in the University of Iowa Libraries?

…the exchange between Lil Picard and Alfred Jensen must be noted. An uncommon instance in which the writings of both parties are extant in one place, the 360 letters from Lil Picard to Alfred Jensen and his nearly 400 letters to her, for a total of more than 3600 pages, constitute an indispensable document for the understanding of both artists, written over the period when one strives to assert herself as an artist and the other is developing the mature style on which rests his international reputation, sharing and illustrating in his letters the evolution of his thinking. Moreover, Jensen’s part of the correspondence contains numerous and valuable insights and anecdotes regarding the art and artists of the period, recounting entire conversations with Mark Rothko or meetings at the Cedar Bar with Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, George McNeil, and Robert Rauschenberg, among others…. Evaluation of Estate, Jean-Noel Herlin

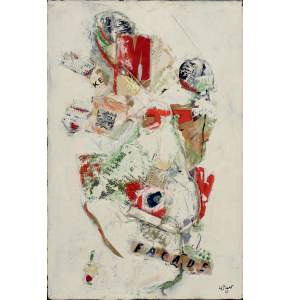

Picard, Facade, 1957. Oil on collage on canvas.

Life As Art

Picard’s collage paintings, her assemblage, even a Streetwork she did in 1969 that involved handing out the junk mail she as an active art journalist routinely received, point to the fact that her art and her life were inseparable

This does not mean her intentions were any less complicated:

I work with the idea of destruction and construction, dematerialization and symbolic references to our society, to the political, sociological, environmental situation and I try through Art and Self-Performance to help to achieve CHANGE for values of humane and spiritual conditions in life.”…..1974.

Lil Picard had nine lives. Yet each time, the spirit was the same: lively, generous, slightly wicked. And don’t forget sardonic. When I met her (in the early ’60s), she was welcoming, known to all as the crazy German journalist who never missed an art opening.

I struggle with genre. She pops up here; she pops up there. She is the chameleon, but her adventure is not, strictly speaking, picaresque. It is picardesque It is either, as they might say in German, a bildungsroman (a novel of education or coming of age like D.H. Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers or Herman Melville’s Pierre), or it is of the subcategory kunstlerroman — an artist’s life, like Voltaire’s Candide or Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man). Is Lil’s life story Portrait of the Artist as an Old Lady? Or it is something else? I never thought of Lil as particularly elderly.

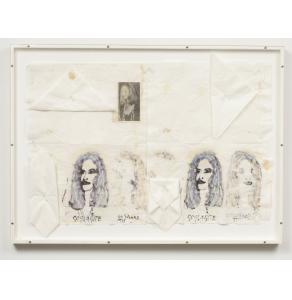

Lil Picard, Untitled (four paint-on-cardboard collage-paintings), 1958-59.

Her Art Comes Alive

Because of the online catalog to the Lil Picard exhibition now at the Grey Art Gallery, everyone has access to my timeless profile published in the Soho Weekly News in 1976, upon the occasion of her retrospective at Goethe House in New York.To enlarge text click on image.

I had already started writing about the Grey show when I discovered this chestnut of mine. It was a shock. I was about to reiterate what I had already iterated 34 years ago. Stop the presses. What could I add now to the Lil Picard Story? Well, interesting details, but otherwise….

Saying something about the art might be refreshing, for the art itself now looks quite good. In ’76, I hardly mentioned it. It has improved with age, or I have, perhaps because time and distance are sometimes the best curators and editors.

Some say the market is. Normally I would beg to disagree, although at the end of a certain, recent artist-autobiography, a gaggle of unsold paintings are illustrated, ripe for the picking and in the artist’s humble opinion some of the best he’d ever done. (He would also like to get rid of them, but that goes unstated.) Well, he’s wrong. Whoever through the years gleaned his output, gleaned well. (This is poor James Rosenquist.)

On the other hand, Lil Picard, a mere woman and an older woman at that, was spared the eyes of dealers and collectors, for she never sold much. In point of fact, way back then, destruction/action/happening/performance environments, such as she began to produce when she hit her stride at age 66 (!), were totally off the commercial map.

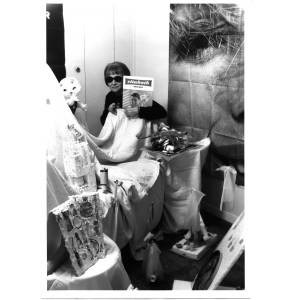

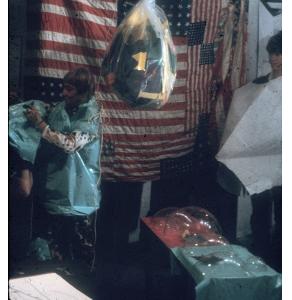

The “relics” of these, assembled to hint at what the environments might have looked like (photos are better in this regard), can now stand alone — not as period pieces or fragments, but as assemblage. Unlike many performances and/or environments, Picard’s major works had conscious content: 1965-2065-2165 was a feminist attack on the cosmetic industry.

Construction-Destruction-Construction (1968) was pointedly antiwar:

I should also point out that her collage paintings, using the corrugated part of corrugated cardboard, are splendid; her napkin “drawings”, such as Socialite Napkin (1975) are poignant and witty:

The burnt-tie piece (1968) alone should be considered a classic. Not only does it say something about penises and patriarchy, that they are her dead husband’s ties adds much more. Yes, they belonged to “Dell” — Hans Felix Jüdell, who changed his name to Henry Odell, her second husband, a German banker who convinced her that she had to escape Nazi Germany with him.

Does her life as an artist have a moral? What do stories or movies mean?

Does her life as an artist have a moral? What do stories or movies mean?

Lil Picard and her dog Carry in front of Hotel Adlon, Berlin, c. 1933.

Hamburger for Hitler

One of Picard’s stories sticks in my mind like a scene from a movie. She lived in Berlin in the days of the Weimar Republic during the rise of Nazism. Every day, Lil used to walk her little dog, a Beddington terrier named Carry. One time, a Nazi stopped her rudely and said: When we take over, not only will we turn your little Jewish dog into hamburger, we will turn a Jewish girl like you into hamburger too.

I have told this story, which is what I thought was Lil’s story, dozens of times, even to students, to introduce Germany between the wars and to vivify what had happened with the rise of Hitler.

Now, looking at the filmed interview by Silvianna Goldsmith that is part of the exhibition: I hear the story again, but as actually told by Lil. In her version — at least the version she told when she was being filmed (c.1981), which might have been different from the one she told me years before, it was the elevator man in her building who suddenly appeared in a Nazi uniform and voiced a too hearty “Heil Hitler.” But he threatened that only her little Jewish dog would be turned into hamburger, not her.

How different is this from my version of 1976, and why?

The full horror came home to her when a Nazi officer tired to pick her up on the streets of Berlin as she was walking her dog. When she rejected his advances — she is Jewish — he told her that her dog would make excellent Jewish hamburger. – “Lil Picard and the Jazz of Life,” Soho Weekly News, March18, 1976

In my 2010 version (see above), I have a stranger stop her on the street. I picture him as a blond Hitler Youth in costume, or a storm trooper. Which is more frightening: a stranger, or to see your ordinary, everyday elevator man transmogrify into a Nazi? Which is better, turning your dog into hamburger or turning both the dog and you into hamburger?

After I had been to Berlin (for an exhibition of my own art), I began picturing the street as Unter den Linden, one of the great boulevards of the world. I stayed in a hotel there once, the same cheesy, modernist hotel that is in former-Berliner Billy Wilder’s One,Two,Three(1961) , the film in which Coca-Cola executive Jimmy Cagney is involved in some East Berlin/West Berlin shenanigans. But the movie seemed to have been made by someone else, not the Wilder of Sunset Boulevard (1950), Ace in the Hole (1951), or Some Like It Hot (1959). It was also Cagney’s Hollywood swan song. The beginning, however, is worth seeing for a glimpse of a still-divided Berlin.

How do movies affect the stories you tell yourself?

Which stopped-by-a-Nazi story is better? My most recent version, of course -which, I now realize, is “Little Red Riding Hood” made even more horrible by costuming and sets.

The content is something else: a self-confessed sophisticate like Picard, a vital participant in advanced Berlin art culture, admitted she did not understand the present danger of, so to speak, the wolf at her door.

Picard was personally menaced and even had her press credentials confiscated because she was Jewish. Yet she still did not want to leave her beloved Berlin. Hitler had become chancellor in 1932; she did not vacate until 1936. She told this story over and over again. Why? To paraphrase what she says in the Goldsmith interview: We did not believe that they could or would do all they said they were going to do when they came into power.

Will some far-out branch of the Tea Party announce plans so outrageous that no one will believe them until they are put into effect? What would it take for you to leave your country? Where would you go?

Picard, Self-Portrait Dematerializations, (detail, successive Xeroxes), 1974.

Life Is Not a Party, Nor Is Art

As someone who has been known to write fiction (I do not mean Artopia, I mean my book of short stories called Hotel Death and Other Tales), I am interested in how real-life events are changed into fiction, need to be so transformed, or are in the telling transmogrified. I am fascinated by unreliable narrators. Slight changes in dates, according to a footnote in the recent biography, make one suspect that Patricia Highsmith’s diaries were at least partially fiction. That is why histories, including art history, are so slippery — and why, in order to change art, you have to change the art-history story.

So you see that this is a very strange story indeed. Here is another mystery: Although in the Iowa City repository there are childhood “artworks” dating as far back as 1910 and most interestingly a photo in the online catalog tagged as “Lil Picard working at a table, c.1934,” that could be her working at a collage, Picard herself (in the filmed interview) indicates she did not begin making art until she met Jensen.

It began with a lie.

When they first met in a downtown gallery, she was embarrassed when Jensen asked her what she did. Picard improvised on the spot that she was a painter. She had indeed taken drawing classes but had not yet studied with Hans Hofmann. So to give her the benefit of the doubt, let us say that only at the age of 52 — when she met Jensen — did she become serious about being an artist, at least in her own mind. In retrospect.

And then there is the role problem. As an artist/writer myself, I am particularly interested in that kind of difficulty. Her way of maintaining financial independence was to write about art. But, oh, she only imitates all the art she writes about. How many times had I heard that about Lil. Artists and others (dealers in particular, and art historians too) want to keep art-making within a particular guild. You can no longer paint in your living room like Edward Hopper or Alice Neel. You need a gigantic all-white loft. Show me your MFA. Competition from art critics and poets? Oh, they might be too clever or maybe not “visual” enough. Why can’t you be both? Just because most artists limit themselves to one, and only one, calling — turning it into a trade instead of a calling — doesn’t mean everyone has to. Picard had contempt for roles and boundaries.

Furthermore, we cannot untangle Picard’s art from the prejudices women have had to face, or from the problems caused by the cult of youth: “The situation of a woman as a painter in New York (at my age) is not easy to handle. The Cedar Bar and The Club are run by cliques and only young and pretty girls are wanted round; it’s a rat race and a racket of the worst sort” — Picard, diary entry 4/23/1960.

Not only sexism, but age-ism as well. Anti-Semitism, sexism, ageism and possibly anti-avant-gardism. That’s a full menu, isn’t it? Nevertheless, Picard scoffed at narrow roles and rigid art categories, defying the commercialization of art. And the results now look pretty spectacular.

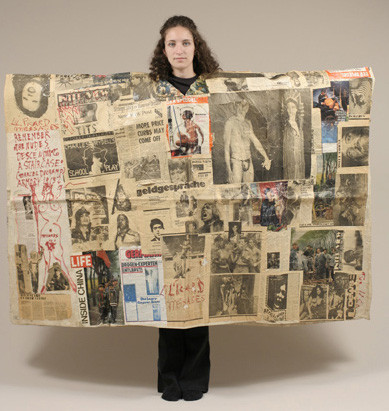

Picard, Messages (performance dress/poncho), 1971

FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT contact: perreault@aol.com