Marina Abramović as Joseph Beuys (Guggenheim Museum, 2005)

MoMA Redeemed?

Marina Abramović (MoMA, to May 31) did not set up the parameters of Performance Art. Though there are only a few years between the seminal (sic) works of Vito Acconci and those of Abramović and her early-Performance partner Ulay, their efforts are surely second-generation. Second-generation, but not second-rate. Oh, yes, art is fast, and a generation can occur in the blink of an eye.

Who are the pioneers? Bruce Nauman and Dennis Oppenheim surely count for something, although their performance art was studio-based (Nauman) or landscape-based (Oppenheim) and neither usually “performed” before any audience other than the camera. Acconci sometimes did, as in his notorious Seed Bed masturbation piece, in which he pleased himself under a false floor in the Sonnabend Gallery. Before these artists, Yoko Ono and Joseph Beuys reigned — and before that there was Yves Klein, with his infamous Leap Into the Void.

Before I go on, for a previous take on Abramović, her recreations of “famous” Performances at the Guggenheim, and my own addendum to the history of the still-fugitive performance genre, please see my Artopia entry of Nov. 11, 2005. Note too that in Artopia we capitalize Performance and Performance Art when these terms refer to the post-’65 genre and do not when we mean performance in general, which may apply to a theater performance or the way an automobile operates.

Chrisopher Marlowe

Does Precedence Exclude Transcendence?

Is first always best? Well, in other realms, that is not necessarily the case. Christopher Marlowe was the first to write plays in blank verse, but none would dispute that Macbeth (1605?) is better than Tamberlaine (1587).

Yet in art, although we like Man Ray’s readymades, full glory goes only to Marcel Duchamp as the inventor of same. R. Mutt’s urinal is better than Man Ray’s metronome. And, closer to home, is not de Kooning still considered greater than Franz Kline?

Abramović is not a Performance Art founder, but she has the noteworthy distinction of making only Performances. In this regard, she is to Performance Art what Allan Kaprow is to Happenings; she has not swerved. I would be surprised indeed if she suddenly began to produce paintings and sculptures for the art market.

We like the freedom that artists now have to investigate all genres, which of course is to their own peril. Early on we had some doubts about those who first gained attention with Performance Art and then moved quite quickly to make saleable products of no particular interest. That most of the Happenings gang went on to make Pop Art did not mean that the tactic was foolproof.

Performances, as most grad-school artists know, were once how you opened the door or lured the customers into the store. We do not have to wonder where Matthew Barney got the idea. But we do not blame the pioneers, really. They did only what they had to do to escape working as waiters or cabdrivers or college professors. But who says you have to make a living with your art?

In Artopia we are entertaining the idea that if you make your living with your art — which includes teaching art — you are not really an artist, but a hack. That does not mean you have to be born rich to be an artist or need to have a rich husband or wife, although this might help. I see nothing wrong with being a short-order cook and an artist.

Of course, grad-school artists now count Performances as part of their kit bags, on the way to stardom. Paintings, sculptures, environments, drawings, prints, videos, and Performances. Well, why not? Throw in architecture too, for good measure. And fashion. We are all Leonardo, or at least Picasso.

Sort of.

Pioneer, O Pioneer

Not only is Abramović noteworthy because she devotes herself to Performance Art, but she is the first of such to be honored with a full-blown survey at the Museum of Modern Art. MoMA, heretofore known mostly for offering its lucrative stamp of approval to artists of a more material bent and more obviously descending from Picasso and Matisse, has taken a gigantic step into … the last half of the last century.

Well, better late than never.

Does this mean that MoMA is now the leading light of contemporary art? If one must maintain a distinction between modern and contemporary art, then yes, definitely. But if you assume that Duchamp is as modernist as Picasso and Matisse, then that distinction is moot. If you assume that Constructivist, Futurist, and Dada performance art were part and parcel of modernism — as I do — then what was so new and dangerous about Performance Art?

I would have liked to see a Carolee Schneemann retrospective first. Now that the MoMA public has accepted full-frontal, real-life nudity, is it ready for Schneemann’s Meat Joy (1964) or Interior Scroll (1974)?

And as much as I hate group shows or 10%-ers (see the previous Artopia, called “Not Just the Whitney Biennial”), an historical survey of Performance Art might be called for. (Of course, even if a museum-generated history of Performance Art is in the making, no one says that it has to happen in historical order.)

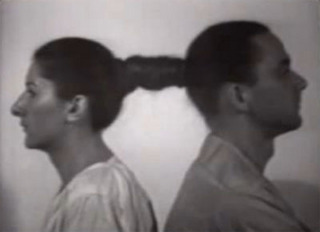

Abramović/Ulay: Relation in Time, 1977

Breaking Another Thumb

In the visual arts, alas, there’s another rule of thumb: the breakthrough art in any artist’s career always wins. Collectors scramble for the fresh. Decline is inevitable, unless the artist is Matisse.

I was all set to proclaim Abramović as conforming to this evil notion, her best works occurring early in her career. Certainly her Performances after her breakup with Ulay (her German lover and collaborator) are in general not as strong as the collaborations. Their couple-ness was new to visual art as content and form. They were never Tristram and Isolde or Castor and Pollux. But at least they were never Gilbert and George.

Ulay holding a poised arrow at Abramović’s heart is … heart-stopping. Seeing photographs of people squeezing between their facing, naked bodies in the various incarnations of their doorway piece Imponderabilia makes the current MoMA re-performance, using buff models with perfect Ken and Barbie skins, seem clinical rather than alchemical.

Abramovic/Ulay, Imponderabilia, 1977

The last Ulay/Abramović collaboration (1988) involved each starting out at opposite ends of The Great Wall of China and then meeting. But instead of marrying, as apparently was the plan, when they met they decided to split. That there was a kind of reconciliation (if you will excuse the term) or reunion during the Artist Is Present Performance – dutifully recorded by all official cameras, video and otherwise – adds a strange but sentimental twinge.

Abramović and Ulay reunited at The Artist Is Present, MoMA.

I should also note we are not into masochism, no matter how the subject, even explored by a woman, may reveal socially objectified sexual roles. And Abramović’s “Balkan” pieces are laughable — perhaps intentionally. We like the Rabelaisian aspect, but we ourselves are not obsessed with Yugoslavia, nor does Abramović convert us to her concerns. Peasants baring their breasts to the rain or humping fields is really not all that funny, or telling. Because Abramović’s family was highly placed in the former Yugoslavia — an Orthodox patriarch, a revolutionary hero, and so forth — it is difficult to see these multiple-screen presentations at MoMA as emblematic of the marginal or the despised, the conquered and reconquered orphan-cultures of the Euro-empire. Let’s put it this way: Abramović is not to the land of Tito what film director Béla Tarr (Satantango, 1994) is to Hungary.

But then, ah yes, we come across the new Endurance Work: The Artist Is Present. She sits all day long in the MoMA atrium, and visitors, one at a time, may seat themselves across the table from her and stare back as long as they want. It’s a masterpiece: so startling and effective, whether you sit with her or not, that it is charisma personified. The piece is also available live online during museum hours: 10:30 AM to 5:30 PM, Fridays until 8 PM, but not on Tuesdays when the museum is closed.

This most recent work explains a great deal. It demonstrates why videos and photographs of older pieces are more effective than the re-performances, using paid nudes. And I go back to imagine how different the original performances must have been when executed by the artist herself.

Unlike Kaprow’s Happenings (the reinterpretations of which have their own set of problems), Abramovic’s Performances are charisma-based. Not any old charisma will do: you need her charisma. Furthermore, had the artist decided to “re-perform” her old works herself, wouldn’t that naked 63-year-old-body set up a different set of meanings than the same body naked at 29?

Saving the Legacy

Saving the Legacy

In the now burgeoning effort to preserve Performance Art — apparently initiated by Abramović herself, bless her – there’s perhaps been too much discussion about re-performance and re-creation and how to make money and not enough about what makes Performances different from most Happenings, most Fluxus Events, and — at the opposite end of the live-art spectrum — theater. These forms are alike in that they are time-bound (like cinema, by the way, and literature too), and persons are the enactors.

Well, maybe there is not enough time to worry about what exactly it is we are trying to save.

Performance Art is suddenly being bought and sold. Sehgal’s Kiss (2002) at the Guggenheim was bought and paid for by MoMA. Performances, therefore, have cracked the plastic ceiling and are acceptable in museums, alongside paintings, sculptures, prints, drawings, and cinema. Is this the end of Performance Art?

Not quite.

What will be bought and sold is the right to present or re-perform, just as you can buy and sell the copyright to a song or a play. That cannot happen with charisma-based Performance Art, because you cannot buy or sell the artist. Or can you? And if you do buy his or her Performance-on-demand, what happens when death intrudes? Goodbye, charisma. Goodbye, artwork. Goodbye, investment.

Unlike paintings and sculptures, which are relics that sometimes retain the charisma or the aura of the artist, Performance Art residue is mostly charisma- and aura-free. Props are just props. The only exceptions I can think of right now are bits of Beuys-iana and a few Ana Mendieta “souvenirs.”

Not one item or collection of items in the Abramović survey is aurific, not even the table of potential torture-instruments offered to audiences of her Rhythm O (1974).

But she herself in the MoMA atrium has enough aura for a dozen retrospectives. That face, those eyes, that stage presence, that way of holding herself. …

Mark Staff Brandl

The Braid: Solving the Historical Mystery

Performance Art is part of the visual-theater strand of the art braid, beginning with rituals and Mysteries. Later, someone had to design the Mass; and artists from the Renaissance down were often required to invent fetes and celebrations as required by patrons of far grander, more lasting commemorations. Futurist and Dada hijinks ended most of that, and visual-theater went wild.

Visual theater, like others art strands, weaves in and out of practice, visibility, and consciousness, assuming a proper and appropriate guise in each new temporal context. Our currently preferred embodiment, once known as Body Art, goes by the name of Performance Art, and for purposes of discussion and analysis should clearly be distinguished from Happenings, Events, Cabaret, and Theater, itself – as in Broadway, Off-Broadway, and Summer Stock.

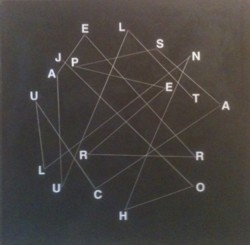

The Braid is the official Artopia visualization of art history — not the staircase, the treadmill, or even the double helix. For a lucid, witty, and extremely helpful presentation of the Braid, see Mark Staff Brandl’s Post-Hysterical: Timeline, Comics and a Plurogenic View of Art History, a lecture presented at this year’s College Art Association meeting in Liechtenstein.Click here.

Brandl cleverly bundles The Braid with the history of the comics. Timelines will never look the same again — or be abandoned to the academic quagmire. Brandl and I agree: if you want to improve the understanding of art, you absolutely must improve the visualization of change. Diagrams based on Darwinian evolution or Hegelian dialectic simply will not do. And, as you may already have suspected, all of Artopia is one big braid. The Braid is a principle of literary composition. Art criticism should embody its subject.

Proposed: Characteristics of Performance Art

1. There are no scripts, as there sometimes were for Happenings and as there usually are for theater.

2. There are no roles, as in theater and some Happenings.

3, Although there may be written descriptions, Performances are not rule-based, as are Fluxus Events.

4. Unlike Happenings, Fluxus, or theater, Performances cannot be performed by just anyone. They must be performed by the artist or artists.

5. Unlike theater, there is no acting. The performer is not pretending to be someone else.

6. As in Fluxus Events, there may or may not be an audience, whereas in Happenings and theater there is always an audience.

7. Unlike in theater and most Fluxus events, but like in Happenings, there may be a residue, which may or may not have artistic value.

8. Everything can be filmed, taped, photographed and otherwise documented without this material becoming a substitution for the primary artwork.

But the artist should always have the last word:

* * *

Marta Minujin: Minucode, 1968

Latin Braids

Shouldn’t Latin American Happenings and performances be included in the visual-theater strand of the Art Braid? A re-creation of Marta Minujin’s 1968 Minucode now at Manhattan’s Americas Society (to April 30) reminds us of the richness of real art as opposed the reductive versions offered in Grad School lectures and seminars; and, alas, in many textbooks and crib notes.

Minujin, an Argentine artist noted for her Happenings and Mass Media art works, took ads out in The Times and The Voice requesting potential Minucode participants to fill out a questionnaire, indicating their principal activities or occupations: Politics, Business, Fashion or Art. And, among other things, were asked to indicate: “What type of materials turn you on? For example: invisible color wall, moving screen, sounds, lights, smells, touching surfaces. Do you like to play with your shadow? To listen to your own voice? To be reproduced in electronic media?”

Four cocktail parties were put together, one for each category, and each party was recorded on film. During each cocktail party participants improvised sound and light shows. The publicity for Minucode was the real artwork. And Minujin worked the p.r. like a pro. Minucode was everywhere as was Minujin in her bleached-blond bangs.

I participated in this piece when it was originally offered, but could not spot myself in the reincarnated wrap-around cinema projections now on view. Surprisingly when I asked myself if I could date the presentation by internal evidence alone or separate the business, art, fashion, and politics cocktail parties, I could not do the latter, whereas the former might only be achieved by noting women’s hairdos. Late ’60s hairdos now seem strange indeed. Otherwise we are now retro in vitro. How odd that the clothes and the men all look the same over so many decades.

See here my notes on a survey called “Latins in Manhattan,” Artopia February 11, 2008, which also demonstrates The Braid in action.

Richard Hendy: Kashima Tetsudo Line, Requium for a Railroad, Spike Japan.

Blong-Blong, or Rust Never Sleeps

A new word is born, right here on Artopia! We are exhausted explaining how Artopia is more than a blog. Not only is it aimed for the ages and carefully looked over by a brilliant editor, it is so much longer than most blogs that it deserves to be called a blong.

SAY IT: “BLONG.”

Speaking of which, here is a link to a blong that I like concerning the downfall of Japan, sort of. Richard Hendy – a British translator living in Tokyo — calls his blong Spike Japan. Best and longest entry is “Requiem for a Railroad.”

Not only was Japan in the forefront of the bubble-burst, with virtually no immigration allowed, a very low birthrate, and the oldest population in the world (more people 100 or over than anywhere else), it is in the forefront of depopulation…and rust. Genre-bender Kiyoshi Kurosawa, in films such as Cure and Retribution, lovingly includes abandoned factories, hospitals, and the desolate Tokyo waterfront.

Hendy’s Requium is more detailed, and in some ways even more poetic. The short Kashima Tetsudo line he investigates is a linear ruin of abandoned stations and rusty railroad bridges. Depopulation? Motorization taking its toll? I myself have perversely taken great pleasure in photographing a totally abandoned shopping mall on Long Island — weeds through concrete, over-turned benches, trash cans still overflowing, a tipped shopping cart the only vehicle in a vast parking lot. But Hendy’s accounting of the ghostly Kashima Tetsudo line is solidified by facts and dead-pan observations.

More Good News for Marina: The Apt App

Yes, Artopia endorses the iPhone. And aside from the “clap app” (Simple Applause) that allows you to applaud yourself with six degrees of intensity (person, people, crowd, laughter, wow, and whistle), our favorite free app is Is This Art? Take a photo of the object in question with your iPhone and the program — provided in part by the Mattress Factory (a longstanding alternative art space in Pittsburgh) — will answer your all-important query.

The Is This Art? iPhone application is a new tool designed for people who have questions about the artistic integrity of their surroundings. Using your iPhone’s camera and a complex, revolutionary algorithm, we now have the ability to instantly provide users with an authoritative declaration of artistic importance.

Made with love in the STEEL City, this app is collaborative endeavor produced by the Pittsburgh-based artists and developers at Deeplocal and the Mattress Factory. Extra-special assistance was lent by C-Monster and WNYC in New York.

An old painting of mine (1998) using polluted beach sand, elicited this response: “This piece is modernist after modernism without being post-modernist, therefore THIS IS ART.”

An old painting of mine (1998) using polluted beach sand, elicited this response: “This piece is modernist after modernism without being post-modernist, therefore THIS IS ART.”

I aimed at the photo of Abramovic’s reunion with Ulay, and received: “Someone who spent most of their life in college wrote an essay about this, therefore THIS IS ART.”

I pointed at a photo of the historic Abramovic/Ulay Imponderabilia doorway Performance and Is This Art? replied: “This makes me feel intellectually inferior, therefore THIS IS ART.”

Is everything art?

No…..

I aimed my iPhone at a recent artwork of my own, clicked, and got this response:

“This work does not resuscitate the referential possibilities of historical stasis, therefore THIS IS NOT ART”

I now have hope.

In any case, I am now looking for a partnership that will facilitate a new app called Is This Good Art? It will make millions

FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT CONTACT: perreault@aol.com