A Whole Lot of Nothing

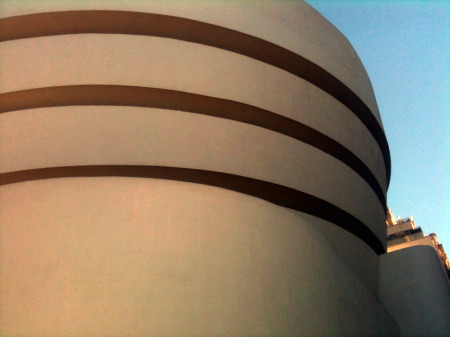

Tino Sehgal has managed to fill the Guggenheim without giving us much to see. But there is plenty to like, not the least of which is the interior of the Frank Lloyd Wright monument to Frank Lloyd Wright. The Guggenheim, all spiffed up at last, has never looked better. It’s the 50th anniversary. My, how time flies…or doesn’t.

The mother of all museums-as-icons (which is a lot to answer for), the kooky Guggie presently looks particularly good because there are none of those annoying paintings by Kandinsky getting in the way of the architecture. Also, the architecture in the 1936 film Things to Come has long been forgotten, as has the 1939 New York World’s Fair and numerous washing machines that predated the look of Wright’s pregnant building — the inside of which is now all lobby, definitely a first.

I have already written an essay about the empty gallery as an artwork upon the occasion of the “Voids: A Retrospective” at the Pompidou last year. But there is so much more to say.

I have nothing but praise for the Guggenheim’s daring move. Two works by Sehgal (to March 10) allows the museum to have it both ways: celebrating the restoration of a masterpiece building and climbing on the performance-art bandwagon, now that the painting and sculpture revival that supposedly wiped out Conceptual-type art has come up empty. Retrospectives for David Salle, Julian Schnabel, or even Jean-Michel Basquiat? Well, not yet, or possibly ever. On the other hand, MoMA is presenting a full retrospective of the performances of Marina Abramović (opens March 14), which will include photos and other documents, videos, “re-performances” and a new work.

Also, an empty museum is very cost-effective, as is performance art. No shipping, packing, framing. The anti-materialist performance strand has reappeared, snaking over and under whatever strands were hiding it in our newly formulated art-history braid. Minimalism is beginning to look luxurious and transcendent.

Nevertheless, in the case of Sehgal even less would have been more. His Kiss (2002) is unnecessary ballast, ruining the metaphor of empty museum = empty art = empty world.

The most important thing about the exhibition is the serenity of a nearly empty museum. Therefore, Sehgal’s exhibition would also be better without Anish Kapoor’s Memory, a welded Cor-Ten steel Easter egg off to the side. And certainly would be better too without the dreary sideshow of modernist masterpieces offered as a sop to tourists. Visitors should be dutifully looking instead for the wall that sports a void that allows you to look inside Memory.

En Garde: Off-Ramp Rants

Of course, you will be yelled at by a nearby guard if you actually come close enough to look inside of Memory — at a whole lot of nothing. Stay behind the line! Stay behind the line! The line is a small strip of tape on the floor in front of the velvety rectangular hole in the wall.

The guard that roared, by the way, was not a guard I would want to see performing Sehgal’s recent Lyon Biennial piece called Selling Out (as reported in the New York Times magazine section a while back). A guard or someone dressed as a guard was paid to slowly strip naked.

Sorry, I know I am being politically incorrect. You probably know that Sol LeWitt once worked as a guard at the Museum of Modern Art, as did the painter Robert Ryman. Just remember this: the guard that yells at you may be next in line for a midcareer survey. Just not the ones at the Guggenheim, if I have anything to say about it.

Then we almost had our iPhone confiscated by another improperly trained, super-aggressive Guggenheim guard. So, unlike the Times, which used an iPhone pic of Kiss (2002) to illustrates its review of the show, Artopia will honor Sehgal’s stricture against photography of his work — throughout all eternity. Let’s see where that gets him. Opening receptions and catalogues are not allowed either.

Kiss, borrowed from the Museum of Modern Art, was purchased by that institution for $70,000. This is one work from an edition of six and was sold solely by verbal agreement. Sehgal can purge art of materiality and paperwork, but not of cold, hard cash. Thus, it is all too obvious that Sehgal (33, born of a Pakistani father and German mother in Great Britain but now residing in Berlin) once studied economics — often referred to as the dismal science, but now enjoyed as the satirical path.

It is obvious that he does not bear truck with the “Scholar Artist” ideal initiated in 16th-century China, according to which it is too vulgar to sell your work or accept commissions — only artisans do that.

It is also obvious that he studied dance. Kiss could be a choreographer’s bow to Rodin. On the empty floor of the Guggenheim rotunda, a succession of prone performers goes through the motions of imitating statues of couples in various erotic poses. Too bad I loathe Rodin. Too bad I would rather have seen all the couples naked.

The couples throughout the day consist of various combinations of gender and skin color; but are age-matched, so there is not a hint of the ever-threatening gerontophilia.

What could I or anyone else do with a digital photo of these sentimental moves? Sell it and make money? Plagiarize dance-that-is-not-quite-dance, make replicas of art-that-is-not-quite-art? Hell hath no fury like a photographer scorned.

I sealed my revenge by writing in my tiny, unobtrusive notebook: If you can steal an artwork by taking a picture of it, then it isn’t much of an artwork.

Another Day, Another Rant

Speaking of notebooks, way downtown at a certain non-museum that calls itself a museum although it has no permanent collection, I was not so long ago witness to an even worse outrage. Persons, including students and art critics, were stopped by another ill-trained or untrained, super-aggressive guard from using pens or pencils to write in their notebooks, because of some fancied threat to the pristine surfaces of the rather inconsequential art surrogates on display.

But it is not pencils and pens I am worried about. After all, you can always use the audio note-taking recorder on your iPhone. You may risk being looked down upon as someone — no doubt a native New Yorker — who habitually talks to himself in public. But we are used to that.

What I am worried about is the camera ban. I fear that panic-spreading, self-aggrandizing copyright lawyers and their paranoid clients have gotten the ears of museums, and, yes, even commercial galleries. Some artists, as you know, will not even allow images of their works on the internet, which results, of course, in zero Google-return and ultimately total invisibility. Doesn’t everyone know by now that the more people who “steal” your images, the more famous you are?

Up the Ramp

Now that I have gotten that off my chest, I can confess that I thoroughly enjoyed Sehgal’s “staged situation,” This Progress, specifically commissioned for the Guggenheim. But first a caveat. If you want to convince everyone that what you are doing is totally, absolutely new, come up with a new name: not “event,” “Happening,” or “performance art.” But what? “Staged situation”!

Sehgal also likes using the word this in titles. Some titles he has already used include This is new; This Success/This Failure; This is propaganda; This objective of that object.

What precedents are there for This Progress? For conversations or verbal exchanges positioned as artworks? Some have mentioned that conceptualist Lawrence Weiner offered conversations for a price long, long ago. Having conversed with Weiner for free, I certainly didn’t fall for that one.

Since Sehgal’s This Progress is thoroughly benign, I thought instead of James Lee Byars’ question performance in 1968. He just sat there — in the once-active exhibition room of the Architectural League — attired in a red robe and his signature black hat, and answered questions. His answers were not particularly interesting, but the answers were really not the point, since the questions were not particularly interesting either.

But Sehgal is not the charismatic, Beuys-ian center of This Progress or any other This. By now — thanks to the New York Times and other publicity vehicles — you already know that you the visitor are greeted by a paid performer, who asks a question and engages you in conversation as you are tenderly guided up the ramp, then passed on to the next “trained participant.” The latter is again a Sehgal term.

Although I am now contemplating calling myself an “art explainer” rather than “art critic” and relabeling my essays “art-awareness texts,” the actual experience of Sehgal’s brand-new “staged situation” was so fascinating that it was the first time I have ever progressed up the ramp all the way to the top. No matter what, I usually take the elevator and work my way down, adjusting to whatever chronological reversals that may entail.

As an art-explainer in disguise, my first encounter was with a very young girl who asked me what “progress” was. I answered that progress would be the elimination of hunger. So, of course, I went on to explain what I meant, and my explanation sort of flooded over into my next encounter, and the next.

Somewhere along the way in one of the pleasant conversations — while strolling upward, ever upward — I had to attack the idea of balance as a proper way to go about things and spouted the idea that there were some things that were good and some things bad; some things objectively true and some things objectively false. I did, however, successfully stymie my impulse to chat about art in terms of good and evil.

But I did rant against the stupid new New York Times category called “Room for Debate,” often attached to topics where there really is no room for debate. The Times is not as bad as BBC News, which not so long ago asked in its “Have Your Say” section if Uganda should debate gay executions. Would we think it fair to allow Hitler to give his side of the “debate” about Jews?

My tour and my special version of Sehgal’s artwork ended with a conversation with a Polish-born woman to whom I confessed I was Polish on my mother’s side. And I found out from her — for by now I was questioning as well as answering — that her greatest relief in coming to the United States 40 years ago occurred when someone told her she no longer had to lie, as was necessary under the thumb of Russian-style Communism. Now, I am wondering if it were a lie of sorts that I did not confess that not only am I half-Polish, but am an art critic?

Of course I liked This Progress. It was all about me, and I am sure others had the same experience.

Progress Is a Comfortable Disease (e. e. cummings)

Sehgal’s answers to questions once raised by the conceptualists before him are charming, but possibly disingenuous. Although I do not wholeheartedly agree with his answers, these are questions I enjoy.

I don’t, however, think that Sehgal has made an advance over the conceptualists, as he seems to claim, just because he has no guilt about selling his artworks (no matter how weird the terms of exchange). He is right about one thing: the conceptualists, in spite of their youthful rebellion, went on to market every scrap of paper they ever marked and every bad photo they ever made.

Nevertheless, one suspects that if our art star of the moment — he is even on the checklist of the Jeff Koons curatorial foray forthcoming at the New Museum (“Skin Fruit,” opens March 4) — continues the trajectory of his blossoming career, somewhere, somehow, someone will offer scripts and other material manifestations of his eventlike, Happening-drenched “staged situations.” And even photographs of them.

And what about his other strictures? No opening receptions, no wall texts, no catalogues. This is progress? I would ban illiterate and irrelevant wall texts and catalogues, for sure. Now if only young Sehgal could add no press, no photographs of the artist, no profits, he would really be saying something new, even though we would probably never hear of him again.

FOR PAST ENTRIES GO TO “ABOUT THIS ENTRY” AT THE RIGHT, CLICK ON “ARCHIVES.” SCROLL DOWN FOR ENTRY TITLES.

FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT WITH EACH NEW ESSAY, PLEASE REQUEST BY NOTIFYING: perreault@aol.com