Antoine Pevsner,Portrait of Marcel Duchamp, 1926. Cellulose nitrate on copper with iron, 65.4 x 94.0 cm (25 3/4 x 37 in.) Yale University Art Gallery. Gift of Collection Société Anonyme. The works originally clear plastic components now show extreme signs of degradation, including warping, cracking, and discoloration, which exacerbated corrosion processes in the metal pieces. Photo: Yale University Art Gallery. ©2009 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris. Caption: GCI Newsletter.

The Doritos Syndrome

If it has never occurred to you how fragile works of art are, start worrying now. Temperature, humidity, and people looking at them can make them age, wrinkle, fall apart. And we can blame artists, too. They persist in playing with time-bound products like fluorescent lights and various video formats; they even distribute and store their art electronically on YouTube. Are YouTube and Picasa eternal? Is The Cloud, located in server forests somewhere in Switzerland or China, invulnerable to time and fortune?

Writers, you are not secure either. The New York State Archives recommends that electronic texts have paper backups and that electronic files be copied every three to five years, even to the point of “migrating” them to a new system.

But art has been asking for trouble for a long time. Artists of the last century indulged in unstable materials. Naum Gabo and his brother Antoine Pevsner enjoyed making sculpture out of cellulose nitrate back in the USSR. So much like glass, but lighter, unbreakable and easier to handle; so new.

At a 2007 conservation workshop at London’s Tate, there were “collective gasps” when an original Pevsner, now looking like a “plate of Doritos,” was shown next to an image of a recently constructed replica of what it had looked like in its glory day.

Cellulose nitrate is bad enough; think of fat and felt; of earth, blood, semen, garbage. Hot dogs.

Carol Mancuso-Ungaro (associate director for conservation and research at the Whitney Museum) in Conservation Perspectives, the Newsletter of the Getty Conservation Institute, reports the following anecdote offered by her British colleague Herbert Lank:

An auction house had received for sale a construction by Beuys of a German U-shaped knackwurst suspended from a rod by shoelaces. Unfortunately the Dutch owners had taken it off the wall overnight before packing. On returning in the morning to do so, they found that a large chunk had been bitten out of the base: their parrot was lying dead on the floor.

Joseph Beuys, when asked about what to do, replied that a new sausage would not be a solution because the original was by then 10 years old, and that the “patina” was an essential element of the work.

“Lank,” reports Mancuso-Ungaro,” meticulously restored the missing part.”

Inherent Vice: When Sleepers Awake

One day you will awaken and realize that all the artworks you love are replicas.

Art was too precious, unstable, and far too difficult to preserve, conserve and insure. The expense was enormous. Since lost monuments of modernism such as Kurt Schwitters’ unfinished and abandoned Merzbau, 1919-37 (1981-83) [above] and El Lissitzky’s Prounenraum, 1923 (1971) had already been replicated from photographs and the facsimiles often accepted as art, it seemed sensible to replicate all art in the face of unpredictable disasters and inevitable decay.

Let there be light. But light of any kind hastens art’s demise. Art objects are vulnerable even to slight fluctuations of temperature and humidity, never mind the wild variations that occur when feedback systems are in error or do not work fast enough to take into account persons daring to gaze upon these ultra-sensitive fetish objects.

We believe in reincarnation. We already know Performance Art can be experienced in restagings and reinterpretations. Pieces by Allan Kaprow such as his 1961 Yard (previously discussed on Artopia) now have a history of official “reinventions.” Long-forgotten Fluxus Events have come back to life, reexisting in restagings by Fluxconcerts and others.

You may not be able to step into the same river twice, but water is always water. Or is it really the other way around? As long as it keeps its name, the river is the same.

In Artopia we have noted the witty works by Stephanie Syjuco in “1969″ at P.S.1/MoMA that are clearly replicas and labeled as such. The “real” works were off-limits and could not be borrowed from MoMA itself because P.S.1 does not have climate control.

Excluding personnel triage and decimated endowments, within the museum field conservation, restoration and replication are the hot topics. Three tasty threads, listed and linked below, make up the main sources of our intertextual braid. Here are tales of despair and repair, wherein even artists are vague and change their minds. If you think that correct labeling is all that is involved, then think again. Here are occasions for your enlightenment, titillation and despair:

Tate Papers: Inherent Vice: The Replica and Its Implications in Modern Sculpture. A multitude of terse papers presented at an international workshop at the Tate Museum are so full of information and complicated points of view they will make your head spin, your eyes roll, and your temperature rise. Info on the works of Gabo, Eva Hesse, Damien Hirst, Helio Oiticica, Dieter Roth, Vladimir Tatlin and others.

Museum: Saving Collections. Not just a pitch for the green museum but a vision gleaned from the field, concerning the future of museums. Rising tides mean historic buildings will have to be moved — possibly indoors. And facsimiles will lead the way to an uncertain future.

Conservation Perspectives: The Getty Conservation Institute Newsletter, Fall 2009. Essential for anyone in the visual arts. David Hockney gets his acrylic painting cleaned; everyone kvetches. Original artworks are seriously wounded or totally doomed.

Cover of Conservation Perspectives

Cover of Conservation Perspectives

Dan Flavin, Untitled, 1976. Pink, green, and blue fluorescent light, 8 ft. (244 cm) high leaning. Dan Flavin Art Institute, Bridgehampton, New York. Fluorescent tubes are no longer widely available in the diameters or colors used by Flavin. Although tubes can be custom-made and stockpiled, this technology will likely become obsolete, posing a long-term challenge for conservators of Flavin’s works. Photo: Florian Holzherr. Collection of Dia Art Foundation. © 2009 Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Caption: GCI Newsletter.

|

|

|

|

Change or Die

In Museum, the journal of the American Association of Museums, Elizabeth Wylie and Sarah S. Brophy (“Saving Collections and the Planet”) summarize the predictions they have gathered: “Professional practice must change, and the power of the original will shift in weight and meaning.”

Some immediate steps to take are more efficient climate control in public spaces; segregated storage; use-keyed lighting. Even in very popular museums, galleries are empty more than half the time. Do the lights have to be on when no one is there?

As Valentine Talland of Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum opines, in the past we knew about light and fading but didn’t “anticipate the burden of access and its role as a variable in deterioration.” Or as summarized by the authors:

Maintaining climate conditions in storage (a controlled environment) is one thing: maintaining conditions in the galleries is another, with variables like heat-producing artificial lights and lots of breathing, moving people skewing conditions so systems must work harder.

The Gardner Museum in Boston originally received 1,000 visitors a year and now entertains 200,000.

” Who are we responsible to, Mrs. Gardner’s display or the Sargent watercolor?” asks Gianfranco Pocobene, the Gardner’s head of conservation. “The museum is replacing some vulnerable textiles and works on paper with facsimiles to ensure their long-term preservation while addressing the historiographic aesthetic of the display.”

The paradox – whether suffered by the preparator, the conservator, or the curator — is this: displaying art is inimical to preserving it.

In this regard, when it comes to artworks on the level of the Mona Lisa or Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, it has long been rumored in Artopian circles that the real artworks have been locked away to prevent theft or damage from persons or the environment, and skillful replicas are employed as unannounced stand-ins.

Artworks are easily faked, sometimes with wicked purpose: aesthetics, irony, destabilization of rigid points of view. See: Sherrie Levine, Elaine Sturtevant, Mike Bidlo and other appropriationists. The skill sets are readily available. Facsimiles could replace every artwork in MoMA or the Met and no one would know the difference unless they were labeled as replicas.

* * *

John Perreault: Mended Rock (for Beth), 2006.

Private collection, Scottsdale, Az.

Mr. Fix-It

And then I was looking through Fall 2009 Conservation Perspective, the newsletter of the Getty Conservation Institute. Yes, yes, I am interested in such things: art and decay; mending things.

I, who once used acrylic paints before switching to Vegemite and then toothpaste (I’m not kidding), actually read “Cleaning Acrylic Emulsion Paintings” by Bronwyn Ormsby and Alan Phenix. Acrylic surfaces are rarely varnished, so there is no protection from dirt and grease. And fingerprints from improper handling? Forget about it. Acrylic is a dirt magnet.

Cleaning agents themselves can be dangerous too and need to be tested by: an HTP cleaning test device; automated image analysis coupled with data mining, and atomic force microscopy; and/or parallel dynamic mechanical thermal analysis and de-absorption electrospray ionization mass spectronomy.

The lead article by Thomas Learner, G.C.I.’s senior scientist, had already set the worrying tone by not only pointing out the ill-conceived use of cellulosic plastics by Gabo and Pevsner, but also the folly of Hesse’s signature employment of untested polyester resins and synthetic latexes. Surely one may wonder if the remnants of a hanging anti-form piece now deployed on the storage floor like the skin of a flayed corpse is really what the artist had in mind to leave for posterity. Furthermore, a partial mockup of a 1968 plastic wall piece fabricated by her former studio assistant using the original molds now in his position, reveals by its ugly transparency the poignant changes wrought on the original sections now surely slated to entirely decay or at least evolve into the totally opaque.

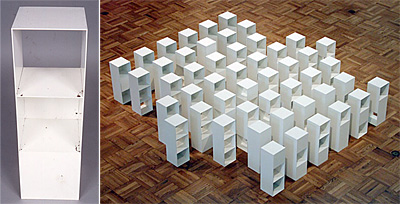

When the artist’s hand was never involved in the first place, restoration may not be a problem. We see a photo showing a rusting section of Sol LeWitt’s 49 Three-part Variations on Three Different Kinds of Cubes next to the completely sanded and re-enameled restoration.

Sol LeWitt, 49 Three-Part Variations on Three Different Kinds of Cubes, 1967-71. Enamel on steel, 49 units, each 23 5/8 x 7 7/8 x 7 7/8 in. (60 x 20 x 20 cm). Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio; Fund for Contemporary Art, 1972. LEFT: Detail of one of the units. RIGHT: Post-treatment installation view. The discoloration and cracking affecting 33 of the units was deemed sufficiently antithetical to the artists intent of a perfectly white, unblemished surface that removal and reapplication of the enamel was considered a justifiable treatment. © 2009 The LeWitt Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.Caption: GCI Newsletter.

In Artopia, we suspect that some masterpieces have been so conserved, preserved and restored that they are no longer the original artworks.

Restoration is a slippery slope. First you replace the discolored plastic parts, then the rusty metal, then the rotten wood — and there is nothing left of the original. It is like the plastic surgery addict who moves from lips and eyelids to full face and then the whole body and wakes up in the morning and looks in the mirror wondering who she (or he) is. Where did the real me go?

It is like Jason’s ship the Argo, now a metaphor for everything postmodern and poststructuralist:

A frequent image: that of the ship Argo (luminous and white), each piece of which the Argonauts gradually replaced, so that they ended with an entirely new ship, without having to alter either its name or its form. This ship Argo is highly useful: it affords the allegory of an eminently structural object created not by genius, inspiration, determination, evolution, but by two modest actions which cannot be caught up in any mystique of creation: substitution (one part replaces another is its paradigm) and nomination (the name is in no way linked to the stability of the parts): by dint of combinations made within one and the same name, nothing is left of the origin. Argo is an object with no other cause than its name, with no other identity than its forms…

Roland Barthes, Barthes by Barthes, Macmillan, 1976

Curiously, one kind of author (the novelist, the artist, even the poet) is subverted in favor of another, lesser kind of author: the critic. The secondary subverts the primary. A deeper understanding of the Argo trope is that there are no art objects; there is only grammar.

The End Is at Hand

And what makes you think facsimiles are not already widespread?

Rethinking the standard denial, Jill Sterrett of S.F. MoMA admits that “we are in the business of making replicas all the time with forms of contemporary art and certainly photography…”

….there have been remarkably creative solutions for tours of a photographer’s work, which have relied on authorized exhibition copies that travel and that allow these works to be seen by millions of people. We copy — or migrate — video all the time. That’s a process that we’ve also accepted as underpinning the way that we keep video installations alive.

And now this:

Although for a short moment he thought that replacing a damaged segment of a Gabo sculpture showing little evidence of the artist’s hand might be fine, Matthew Gale, head of displays at the Tate Museum, confesses he went on to think that…

…the presence of that thing in the world would raise questions. Does it [the artwork with a replaced part] adequately substitute for the original? If the original becomes completely unrecognizable, does the aura inevitably migrate to a second physical object? I seems to me that it does.

The Curious Case of the Migrating Aura

Let us consider Performance Art revivals, interpretations, restagings, replicas, recreations, reinventions. Is the James Lee Byars’ Question Piece the same performance piece if the long-dead artist is played by an actor? That actor’s stage presence is not Byars’ stage presence. Similarly, it may be impossible to replicate Beuys’ How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, or, perish the thought, a John Perreault Circumambulation ages hence, when the digital files have disintegrated and the YouTube Cloud has dispersed.

Perhaps my presence will migrate somewhere too, the way Gale suggests an aura can migrate from an artwork to a replica.

Not only do we want to understand the use of the word aura in art before Walter Benjamin’s famous essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” we want to know much, much more.

In Artopia, we know that aura in art is suspiciously like charisma, which in turn is like stage presence — charisma and stage presence ascribed to persons rather than objects.

Max Weber defined charisma as:

…a certain quality of an individual personality, by virtue of which one is “set apart” from ordinary people and treated as endowed with supernatural, superhuman, or at least specifically exceptional powers or qualities. These as such are not accessible to the ordinary person, but are regarded as divine in origin or as exemplary, and on the basis of them the individual concerned is treated as a leader.

Change a few words and the subject could be the aura in art.

But is aura a figure of speech, as in Benjamin, or a substance, as in common usage, allowing it to swell, shrink, attach and detach itself, even migrate? And what is the relationship of aura to mana? Or mana to…

Adur — Basque

Asha — Iranian

Ashe — Yoruba

Ichor — Greek

Inua — Inuit

Ka — Egyptian

Maban — Australian Aboriginal

Manetuwak — Leni Lenape

Manitou — Anishinaabe

Numen — Roman

Orenda — Iroquois

Prana — Yoga

Seid — Norse

Sumesh — Salish-Kootenai

Teotl — Aztec

Vaki — Finnish

But perhaps artworks do not have to have auras to be art. In 1936, Benjamin claimed that photographs and movies were without auras and therefore — mysteriously, I think — suited for left-wing politics. But Sergei Eisenstein, on the left, was not the only one making propaganda films.

Had not Benjamin seen Nazi newsreels or Leni Riefenstahl’s 1934 Triumph of the Will?

Few would doubt now that photos and movies can be art. Both can serve power, as did the Benjamin-identified auratic art that came before, but now it is corporate power. And many, I will guess, think they perceive cinema-aura and photo-aura — not only emanating from relics of discarded image-snatching systems, but for current products, much aided by the photogenic presence of actors and the crude uses of myth.

One wonders if the application of aura can be taught in the same way some claim to teach “presence” to rock-star wannabes and fledgling belly-dancers.

An eye-opening treatise by a Middle Eastern dancer by the name of Amira Jamal is not a tease but a tip sheet full of counterintuitive advice: focus your gaze over their heads, over and beyond their eyes.

NOT having constant eye contact, especially if on a raised stage, is an important element to stage presence. Yes, you read right: NOT having eye contact. A performer has to look out over her audience.

Yes, every once in a while, you should make here-and-there eye contact, but make it a habit to look out beyond and up. If you just skim the heads of the audience, for the most part, you will give the impression you are making full eye contact. An audience member will know that you are not making eye contact with him/her, but he/she will be certain you are making it with someone else!

That may explain Marilyn Monroe’s screen presence. She was myopic and shy, never looking the camera in the eye. I am definitely going to try this out when I speak at the National Council on Education for the Ceramics Arts conference in Philadelphia this spring. A bit of extra presence can’t hurt that shindig.

Charisma — the aura of persons — may also be a matter of staging. Look strange. Appear bigger than life or wear a funny mustache. Enter from stage right. Position yourself at center.

I really don’t want to Satchmo you. When asked to define jazz, Louis Armstrong would answer, “If you have to ask, you’ll never know.” Art historians, critics, curators, and connoiseurs have been known to say the same about the aura in art.

Aura, it would appear, is the mysterious, unseen essence. Nevertheless, creating aura in art is easy. It’s all done with positioning, with spots and pedestals. But the price tag says it all.

Perhaps we should do some testing.

Aurafication Is My Vocation

1. The Bauhaus Test

Go to MoMA’s website for their splendid design show: “Bauhaus 1919-1933: Workshops for Modernity” (to Jan. 25).

Watch the László Moholy-Nagy movie.

Read everything and look at everything: all the texts, photos and reproductions. You can do it sitting down. Take Kandinsky’s color/shape test. Should a triangle be red, yellow or blue? You can compare your choices with those of his Bauhaus students…and the meaning of this? Well, never mind.

Then visit the exhibition at MoMA and compare your experience. This is the perfect exhibition to use in search of the aura, since the Bauhaus inaugurated the valorization and/or the aestheticization of mechanization in an influential way.

Clues: I personally thought Moholy-Nagy’s Lightplay projected near his Prop for an Electric Stage, itself the subject or “creator” of the abstract moving shapes captured on film, was more interesting at MoMA than on my computer by itself. I felt the Anni Albers weavings, sort of humdrum at home, were glorious in person. But couldn’t decide between aura or increased sensory data as the cause. I mean, after all, weavings in real life are not simply flat the way they appear on your screen. They have texture.

Clues: I personally thought Moholy-Nagy’s Lightplay projected near his Prop for an Electric Stage, itself the subject or “creator” of the abstract moving shapes captured on film, was more interesting at MoMA than on my computer by itself. I felt the Anni Albers weavings, sort of humdrum at home, were glorious in person. But couldn’t decide between aura or increased sensory data as the cause. I mean, after all, weavings in real life are not simply flat the way they appear on your screen. They have texture.

2. The Replica Test

See if (a) art students, (b) artists, (c) art critics, (d) curators, (e) collectors can tell the difference between artworks and their replicas in matched pairs. The works must be unknown to the subjects. Therefore, it will be necessary to commission paintings — we will limit ourselves to paintings — from unknown artists. Then these in turn will be replicated by others. Or, because artists have been known to make replicas of their own work for financial gain, perhaps each replica should be made by the artist who made the original.

3. The Aura Test

Using the same art victims as subjects, ask them to choose which artworks in The Replica Test, if any, possess aura.

I am sure you are beginning to have that sinking feeling. If an art object is vulnerable to time, then so are we. Art stands for a kind of immortality. No one wants to be reduced to a plate of Doritos or end up looking like a cosmetic surgery victim. Furthermore, if we cannot tell the difference between an original and a replica, then perhaps we can’t tell the difference between right and wrong, friend and foe.

And is Kenneth Baker friend or foe? Can art criticism be simulated?

The San Francisco Chronicle’s conservative art critic bottomed out his New Year’s list with this:

Cultural critics have decried simulation creep since the 1930s, but in century 21 the Internet has exponentially exaggerated the false equivalence of reproductions and realities. Postmodernist declarations of the end of originality played their nefarious part – though when did we last hear one? Even a critic who stands for nothing else nowadays must still stand for direct encounters with artworks.

We should know better. We need to mend our ways. Given the Readymades of Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray (they are so 20th century), and given Conceptual art, which is everywhere, we are already halfway there. If an artwork is replaced by a replica, should we be disappointed?

No. Art is in the idea, not in the manifestation, which is merely the vehicle. Plato would be thrilled. We need not mention Benjamin and Barthes ever again.

NEVER MISS AN ARTOPIA POST….

FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT PLEASE CONTACT: perreault@aol.com