What do these images have in common?

Top left is from “Icons of the Desert: Early Aboriginal Paintings from Papunya”

at the Grey Art Gallery, N.Y.U., 100 Washington Square East, to Dec.5.

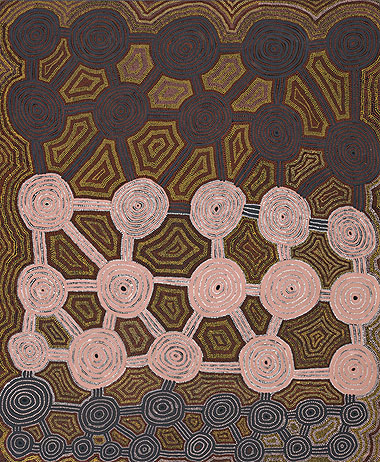

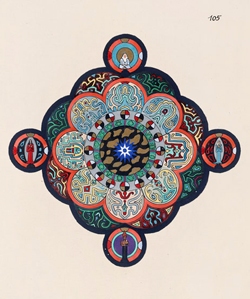

Top right is from “Mandala: The Perfect Circle: at The Rubin Museum, 150 W. 17, to Jan. 11.

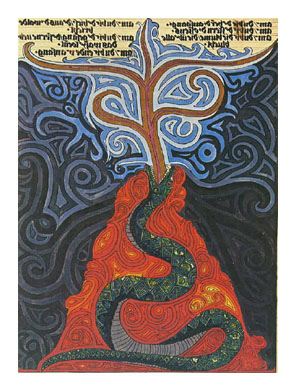

Lower middle is from “The Red Book of C. G. Jung” at The Rubin Museum, to Jan. 25.

Codes, Maps, and Building Plans

Some images and objects we can only see as art by separating them from use, and, therefore, since use is meaning, separating them from meaning. This is not necessarily to fulfill some dubious agenda that defines art as form alone. It may be because we do not understand or want to understand the use intended or have no way of experiencing the belief required.

We are expected to appreciate cathedral décor whether or not we subscribe to Christianity. So if we forgive da Vinci (and, let’s face it, Chagall — whose work has some relationship to Judaism or Kandinsky who was Theosophical) then why shouldn’t we make allowances for Australian Aboriginal paintings,

The Red Book of Carl Jung, and Tibetan mandalas. Most of us do. But should we?

In ancient times — you know, like the Sixties –I was accused of at least three sins. “John,” said one artist friend, “I love your writings, but you are always solving problems I didn’t know I had.” And then, from another: “You are always arguing with yourself.” Finally, proclaimed another artist friend: “You are always writing about yourself,” meaning, I still think, instead of writing about me.

The first is the critic’s duty, which is to see what the artist is not aware of and to say what the artist cannot say. The second objection is also based on ignorance, but ignorance of the dialectical mode of expression. The third objection can only be answered in terms of the rhetorical disclosure of the personal as a sign of the instability of any statement. Unlike the royal “we,” the first person in criticism reveals the possibility of bias in all writings, which is why it is usually forbidden. The author is not hidden. It is also an easy way to

include a wide range of material

Teaser: I am thinking of the Sixties because of “1969” at P.S. 1, but I hope to get to that exhibition, if only briefly, next time around. After all, I am in it, right?

In the meantime, I hope I am still solving problems you didn’t know you had. The problems you know you have are most likely already solved. And nothing has changed, has it?

In regard to the second objection, I wonder what that artist would now think of my current writings, since herein the dialectical has been superceded by the braided.

In regard to the third objection, the only thing I would add now is the clarification that the first person is as much a fiction as the third.

But Is It Art?

Here I want to make the case that we should not look at Australian Aboriginal paintings, Jung’s visionary drawings (1902-1913), or Tibetan mandalas as art, for to do so is reductive.

Yet so much depends upon Marcel Duchamp. Both The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1925-23) — see above illustration — and Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas… (1946-1966) are so opaque they seem to be resultants of alien equations, obscure investigations, secret rituals, maps of other states of consciousness.

This too is the charm of the Aboriginal paintings now at the Grey Gallery, the Tibetan Buddhist mandalas at the Rubin Museum, and the images from Carl Jung’s long-suppressed record of his possibly transcendent ego-trip.

Because the forms in each of these exhibitions are determined by extra-aesthetic motivations and/or content is why they are so vital. They really are derived from alien equations, obscure investigations, secret rituals, maps of other states of consciousness. The forms, splendidly anti-compositional, could not be arrived at any other way. They were generated by other than aesthetic means.

Down Under

I knew of the Aboriginal paintings much before I visited Australia, but once there as Guest Professor of Something or Another in the capitol city of Canberra, I could not avoid them. They are even depicted on postage stamps. There are now as many Aboriginal artists as there are Euro-Australian ones, which means there is a higher percentage of Aboriginal artists within the indigenous population than the percentage of artists among the Euro-Australians. This does not mean that the art market has solved the poverty problem for indigenous peoples of the sub-continent. Art projects rarely solve economic problems, particularly ones based on colonialism and racism. Nor does it explain why some “dot paintings” go for more than any white Australian equivalent. The latter, however, explains why there are so many fakes.

After my teaching stint – punctuated by several trips to beautiful Sydney and a quick visit to my hero “Such is life” Ned Kelly’s jail cell in Melbourne – I felt I had to visit sacred Uluru, dead center of the Australian desert. I needed something to balance Kelly’s gallows irony and the fact that he, as the Australian Robin Hood, arranged that the mobs of well-wishers at his public hanging receive free press-photos of his Irish bandit-visage.

We flew to Alice Springs and then drove along that same straight-edge, one-lane, unpaved highway we had seen from the air, all the way to the Aboriginal sacred rock, once briefly known as Ayers Rock by the white guys. Although now surrounded with three rings of tourism, Uluru mysteriously still glows purple at sunset. There are three-tiered accommodations: Luxury Hotel, Mid-Range, and Camp Ground. And yet….I still felt I was on another planet. The indigenous peoples are right: this is a sacred place. I circumambulated the rock, or at least dreamed I did.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but 150 miles from Alice springs on the Papunya reservation was where the dot-paintings began. They were sparked by the non-Aboriginal schoolteacher Geoffrey Bardon in 1971.

Mick Namararri Tjapaltjarri (1927-1998), Uta Uta Tjangala (1926-1990), Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula (1918-2001) and other talented “artists” took to using acrylic, on boards and then on canvas. Herded together from different tribes, they embraced both the opportunity of giving voice to their 30,000-year-old (!) cultural traditions and the possibility of some ready cash.

Although at least once-removed from their origins in the story-telling, ground painting, body painting of the ineffable Dreamings, the paintings now at the Grey Gallery possess some of that numinous, unearthly aura that spooked me out at Uluru. Dreamings, after all, are one-part deed-keeping, one-part mapping, one-part conjuring, one-part creation myth.

The credentials of the works at the Grey Gallery are impeccable. They are from the first 1000 Aboriginal dot paintings ever made. All were painted at the beginning of the art movement and pretty much before tribal elders grew increasingly insistent that secret, sacred imagery be fully disguised by dots. It is ironic, therefore, that the works are sometimes known as “dot paintings” – i.e. paintings that feature imagery that has been erased.

Some of these diagrams or maps, like the illustration above, are still taboo for aboriginal women and children and are so-designated at the Grey Gallery, where such are grouped in the lower gallery. The images are ports of entry for ancient entities. The gendered nature of the Dreamings — a bad translation of an Aboriginal term for timelessness — suggests their initiatory character.

Tibetan mandalas can take the form of temporary sand paintings. Surprisingly far from Tibet, the Aboriginal paintings are inspired by indigenous sand-paintings, which, in turn, relate to mandala-like Native American ground-works.

Aboriginal ground-painting being made for opening of “Icons of the Desert,” Johnson Museum, Cornell Univeresity. Earth, dye, dried flower petals.

![]()

Finished ground painting…image courtesy Ithica Journal.

Carl Jung would have been pleased by these synchronicities, but he would also have been pleased by more evidence of gender-divisions in the realm of the spirit, the perpetuation of which was one of his personal, very deep flaws. The man, as you shall see, had problems.

Too Jung, Too Foolish

C. G. Jung’s The Red Book (1913-1916) has been suppressed until now. An expensive facsimile edition is now available from Simon and Schuster. Pages from this facsimile and other documents make up an exhibition at the Rubin Museum. At first one might wonder why a museum devoted to the art of the Himalayas would have an exhibition center around an early hand-calligraphed notebook by Carl Jung. But, don’t worry, this too shall be clarified.

Apparently Jung’s family and other interested parties thought The Red Book would put him and his discoveries in clinical psychology or depth psychology in a bad light. And yet Jung himself said it was during the strange, inward-looking period of The Red Book that he came across all the ideas we know think of as Jungian. Everything can be traced back to his scary experiment, probing or yielding to his own troubled depths. His idea of scientific research was to turn in on himself.

Some related material now on display at the Rubin are pencil-drawings of mandalas he made in 1917, when, as he himself later wrote, he found his anima, or, to simplify, his feminine side. “She” was not all sweetness and light. She – everyman’s Lilith – never is. To some she may be Beatrice, but to Jung she was — although he did not call her that — Kalachata’s Vishvamatr, but not so much as an embodiment of bliss, but rather as the personification of Kalachata’s wrath. And yet the anima is also supposed to be the embodiment of every male’s repressed spirituality. Who said Jung indulged in simplifications?

About his own mandalas he wrote:

About his own mandalas he wrote:

“My mandalas were cryptograms concerning the state of the self which was presented to me anew each day…I guarded them like precious pearls….It became increasingly plain to me that the mandala is the center. It is the exponent of all paths. It is the path to the center, to individuation….”

Jung’s journey was the Orphic descent. If he had been more cognizant of Islam, one wonders if he would have had a Mohammedan ascent instead.

Are these pages art? Oh, no. In spite of the careful, obsessive calligraphy and the tidy pictures in the he Red Book were not intended as art.

In Memories, Dreams, Reflections (1961), based on extensive interviews, Jung recounts his encounter with his anima and her insistence that what he was doing in his notebooks was art. “I said very emphatically to this voice [that of his anima] that my fantasies had nothing to do with art…No, it is not art! On the contrary, it is nature.”

Further:

The anima might then have easily seduced me into believing that I was a misunderstood artist, and that my so-called artistic nature gave me the right to neglect reality. If I had followed her voice, she would in all probability have said to me one day, ‘Do you imagine the nonsense you’re engaged in is really art? Not a bit.’ Thus the insinuations of the anima, the mouthpiece of the unconscious, can utterly destroy a man.

Now, I must admit, that unless you are attuned to Jungian prerogatives, to the tempting revelations of the Gnostic heresies, to Sixties New-Age ways of thinking, and to non-western spiritual traditions, you may find this material, if not extremely iffy, then totally insane.

I quarrel with Jung’s quaint insistence upon radically different male and female souls. Excuse me. In my experience, women simply are not more spiritual than men, nor are men more logical than women. Jungian individuation may involve a symbolic androgyny, but this in Jung’s theology is built upon a sexual dualism that is untenable.

Nevertheless, in Artopia we understand that Jungian therapy – and it’s world-view – leaves more room for art than does Freudian psychoanalysis. Jung opened up new paths of inquiry and almost became the magus he thought he was. After personalizing and getting his anima under control, Jung delved into alchemy and the Kabbalah, as well as the I Ching and the Taoist Secrets of the Golden Flower. The woman who owned the gallery I showed with in the early Sixties never made a move without consulting the I Ching.

An exhibition such as this quiet display honoring The Red Book – the Jungian Holy Grail — could force you to delve a bit deeper into Jung, which, I know, you have probably been avoiding. But just try to forget that not only Herman Hesse but also Jackson Pollock underwent Jungian therapy.

Peeling back the layers of time, you had also better be careful when you read about the Buber/Jung controversy. Nowadays perhaps better known as a champion of Hasidic mysticism and the simplifier of the Hasidic teaching-tales then as an Existentialist philosopher, Martin Buber in full philosophical fury accused Jung of being — surprise! — a Gnostic. In other words, a dangerous, polytheistic, dualistic heretic out to destroy monotheism. Briefly, Jung was “mystically deifying the instincts instead of hallowing them in faith” and thus promoting “a modern manifestation of Gnosis.”

Jung gave empiricism as his self-defense. And then Buber responded to that disengenious claim.

Of course, Buber was right, although he himself seemed to have forgotten that Hasidism is rooted in the Kabbalah, with its suspicious Little Man and Big Man. And, yes, all those emanations and broken vessels. And is the Shekinah not God’s partner? Oops.

We have had more than hints of Jung’s shamanistic plunge before the publication of The Red Book. Jung’s The Seven Sermons to the Dead, written in 1916, has been available in English since 1961 as an appendix to Memories, Dreams, Reflections.

This high-strangeness purports to be a text written by the real-life Basilides, a second-century Gnostic. Although much of it is pompous paradox — Jung unlike Freud was never a stranger to pomposity — the effect is hair-raising. It may have been automatic writing and/or dictated by whatever foot-loose and meddlesome spirits were hiding out in Zurich at the time or it may have been pieced together from texts of medieval heresy trials, but Jung was on the same wave-length as the Gnostic texts found at Nag Hammadi, much later. Basilides/Jung even claims Abraxas as the god of this world. Thus this creepy little hymn to dualism begins:

The dead came back from Jerusalem, where they found not what they sought. They prayed me let them in and besought my word, and thus I began my teaching. Harken: I begin with nothingness. Nothingness is the same as fullness. In infinity full is no better than empty. Nothingness is both empty and full….

Well, yes, sort of.

Gemstone with image of Abraxas, one of the Archons, n.d.

Inside A Tibetan Mandala

Onward and upward to the 5th Floor of the Rubin Museum, for a breath of fresh air: The Five-Deity Mandala of Amoghapasha (8-9th Century), The Kalachakra Mandala (c. 1650-1700), and many others plus a pixilated projection of a sand mandala being made, projected horizontally, but minus hands, monks, funnels.

Many years ago I watched a Tibetan sand-mandala being made, and saw it, as is the custom, then destroyed. I also interviewed the Dalai Lama.

As a kid, having read James Hilton’s Lost Horizon, I identified with Tibet. An important character in that fantasy is a priest named Father Perrault, obviously a great-uncle of mine. My last name has been spelled both with and without the second “e.” My imagined cousin, movie-star Gigi Perreau, dropped the last two letters. Here is a clip from the wretched 1937 movie version of Lost Horizon that features buildings in Shangri-La obviously, designed by one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s lesser students.

Both Father Perrault and Gigi (and soccer stars too numerous to mention) were obviously all descended like myself from Charles Perrault of the court of Louis XIV, first secretary of the French Academy and, more importantly, the transcriber of the Tales of Mother Goose, which include Cinderella, Bluebeard, Beauty and the Beast, and Little Red Riding Hood.There is also the notorious Perreault Gang of Canadian highwaymen, but let’s not go there.

Charles Perrault (1628-1703)

Years after my brief encounter with the Dalai Lama, I visited Beatrice Wood – she who had been a cohort of Marcel Duchamp — at her ceramics studio in Ojai, California. It was and is on land owned by the Krishnamurti Foundation. The woman sometimes referred to as the Dada Mama pointed out the view from her terrace. She was 100 years old. The distance hills, she claimed, had been filmed as the foothills of the Himalayas for the Frank Capra movie version of Lost Horizon ( 937). No wonder I felt at home.

To make a long story short, I have written about Tibetan mandalas before, and, although surprised by several aspects of the current exhibition, I was not planning to write again. Until I realized I had a triple-header on my hands.

The exhibition is, of course, a glorious array, showing some of the earliest mandalas now extant. But what impressed me this time was not so much the paintings on cloth, but the three-dimensional manifestations.

Briefly, the Tibetan mandalas in the Tantric Kalachakra tradition, whether painted on cloth or actualized as ephemeral sand-paintings, are air-views of temples. But these are no ordinary temples. Properly instructed and in the right frame of mind, as you wind your way around the corridors and up the stairways — circumambulating the center and the pinnacle– you will get closer and closer to Buddha-hood. Various “deities” will materialize, bur fear not, like everything else in this world, they are only illusions.

Kalachakra and his consort, bright-yellow Vishvamatr are at the center of the labyrinth, male and female united. At this center, which is also the peak of the temple, you will become the Buddha. All of this used to be top secret. However, unlike Aboriginal elders, Tibetan Buddhists have realized that nothing is so secret as what is readily available.

Two three-dimensional mandalas made of metal are at hand. They could be architectural models, but they are much more: aids to helping you visualize your path through flat versions of themselves. If finding your way through the pathways of the mandala is in order to increase your powers of visualization, then isn’t a 3-D model cheating? Probably not. As far as I know you are not punished for being a few counts off in your required number of repetitions of the Jesus Prayer — or any given mantra. Stories too are told of seekers repeating the wrong section of the Talmud or the wrong quotation from the Koran, but still attaining results.

In any case, through these metal “sculptures”, you are led to really see that Tibetan mandala “paintings” are not only diagrams of the world, but temples you are supposed to enter. The digital version – which may be cheating to the third degree — was made as a collaboration between some Tibetan monks and the computer department of Cornell University. It’s part of the exhibition. Here is a a version:

Now do you understand it when I say that Tibetan mandalas — like Aboriginal Dreamings and Jung’s illustrations in The Red Book – are not art works? They are spiritual tools.

YOU TOO CAN HAVE AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT BY E-MAIL

CONTACT perreault@aol.com. MORE johnperreault.com

John Perreault is on Facebook.

You can also follow John Perreault on Twitter: johnperreault