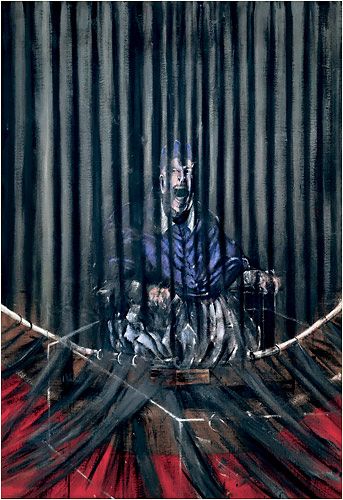

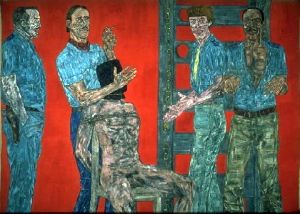

Francis Bacon, Painting, 1946

Bacon Fat

When it comes to Francis Bacon (1909-1992), less is more. The current “Centenary Retrospective” at the Metropolitan, on view through Aug. 16, is ample proof. One picture at a time can be quite effective, but seeing any Bacon that once might have taken your fancy (perhaps out of some deep-seated perversity) along with others of the same or far too similar ilk destroys any credence he might once have had as a major artist.

A deep appreciation of Bacon’s fat is greatly helped if you are 13. That was probably when I myself saw a reproduction of his famous Painting, 1946, owned by the Museum of Modern Art: the side of beef, the open umbrella, the mouth full of teeth, the microphones. And later I saw, in other paintings, nude men doing unmentionable and possibly erotic things to each other. Were the figures taken from Muybridge’s blatant studies of scantily clad male wrestlers? Of course. That made them even more naughty. Back then there was nothing worse than copying from photographs. Hmm. No, there was something worse: copying other artists. Bacon’s major inspiration was midcareer Picasso, all bloated body parts and sometimes screaming mouths. And Bacon did copy Velázquez.

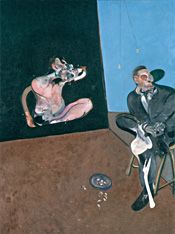

Bacon’s screaming Velázquez popes? Anyone growing up gay in the ’50s had good reason to hate the church, even if one had not been molested by the parish priest. Surprisingly, Bacon tried to deny that his work was in any way autobiographical. He denied personal expression. He denied story-telling. In art, loud and frequent denials are sometimes proof. During his checkered life, our artist of the moment — now brought back from the dead — stopped one biography from being published; but he was not above exploiting notoriety for career’s sake. Bacon tried to have it both ways.

The love of his life, the chunky George Dyer, was a thief, and Bacon loved to say that he first met him when he caught him robbing his apartment. He painted Dyer over and over, for, you see, the artist had discovered early on that the best insurance against blackmail was to be truthful to all about his personal life. Or personal lives.

Nevertheless, in 1977 Bacon stopped the publication of what was to be Michael Peppiatt’s Francis Bacon, Anatomy of an Enigma, finally published in 1996. “As with several other projects to which Bacon initially lent his support,” writes Peppiatt, “he drew back at the last moment, fearful — for all his recklessness — of revealing ‘too much’ about his life.” It is my main source here.

Minus all the tedious art-world details and descriptions of the art, the book could be made into a movie, a horror movie.

Bacon: Study After Velázquez, 1950

Where’s the Bacon?

If only I could like the paintings. If only I could be 13 again. And anguished. But contrary to the rule in most fiction, I wasn’t anguished about my sexuality. Even I knew that the self-punishing homosexual was a self-hating, self-indulgent, literary invention by Proust, Gide, and yes, even Genet. Was I the only one who had read Walt Whitman? I was anguished because, down on the farm, I could not get any. I wanted love. I wanted action. Not torture and slabs of meat.

If Bacon’s paintings are really about anguish in general and not about homo-anguish in particular, then I can live with them. Otherwise, they stand to confirm a demeaning text: gay men are not men, they are guilt personified.

So do we delight in the fact that Bacon let it slip that he liked to wear women’s underwear? That he had a collection of twelve Rhino whips? Yes, we do. And we sort of wish these facts were on the Met’s august walls. Instead, one text actually suggests that the paintings, done by an avowed atheist, are what the world looks like without God. Viewers stand in front of this so-scholarly assertion looking puzzled.

It would be more accurate to say that the paintings are what the world looks like without art criticism. Bacon let it be known that he destroyed a lot of his own paintings, apparently as part of his down-to-the-line studio practice. If nothing else, this exhibitions proves he did not destroy enough.

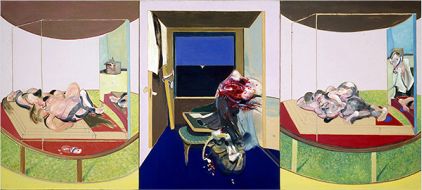

Bacon: Three Studies for a Crucifixion, 1962

BLT (Blatant Lascivious Teasing)

But I want more details on those wall texts. I want to know if Bacon liked wearing bras or panties or both? How British. And in terms of what was once called the English Vice, I want to know who was handling those whips, exactly what was being done with them, and how often. That would be more interesting than the proclamation of Bacon’s atheism. After all, technically speaking, Buddhist too are atheists.

But please, if a new wall text goes up detailing Bacon’s sexual fun and games, I would urge that it be spelled out that, at least in Great Britain, more heterosexual men wear bras and panties and use whips than gay men do.

Why was Bacon so over the top? Surely, if you are treated like a criminal, you will act like one. Bacon operated largely during a time when homosex could result in life imprisonment even if you were already in prison. (And before that, the gallows.) If you have everything to lose, than what the hell? This may explain some of Bacon’s carryings on: gambling, rent sex, lipstick and dyed hair, and sex with his uncle — in Berlin, where said uncle was supposed to make a man of him. This was set up by Papa Bacon, soldier, horse-breeder and man’s man.

Papa Bacon simply could not understand why Baby Bacon broke out in a horrendous, possibly life-threatening asthma attack every time a dog came near or when he was forced to visit his father’s much-cherished stables.

Francis Bacon, Untitled Rug, 1929 (not in exhibition).

Francis Bacon, Untitled Rug, 1929 (not in exhibition).

The bad thing about Bacon’s paintings is that they may be used to affirm the crazy notion that all gay men are heavy drinkers, high-stake gamblers, sadomasochists, high-society hanger-ons, interior decorators (which is how our Bacon began, along with designing modernist tubular furniture and rugs), homebreakers, walkers, and self-hating exploiters of the working-class hunks and handsome second-storeymen who are wandering around everywhere looking for someone rich to buy them a few beers.

I assure you, we are not. Some of us are even married — to other men, at long last, much to the relief of the guardians of house and home and much to the profit of the matrimony industry.

Two Studies for a Portrait of George Dyer, 1968

Although yours truly in his youth also had a second-storeyman as a lover (this is true), it was only briefly. Bacon kept George on for years, declaring him the most handsome man he had ever met and made him pose for the photos that became the paintings now so celebrated for their “anguish.” Poor George. Judging by the paintings, he earned his keep, then died of an overdose. Tellingly, the run of portraits that proliferated after George was out of the picture are simply not as good: horror for hire, bread-and-butter bunk.

But more about Bacon’s childhood, if you can stand it. In some sense, his childhood lasted all of his life.

The Nanny

Not only did Papa Bacon throw Baby Bacon out of the Bacon Irish Manor House when he was a mere teen, Mama Bacon didn’t like him much either, telling him he was so ugly no one would ever like him. He was indeed a pie-face. Photographs do not lie. Possibly in revenge, he later “adopted” his childhood nanny, who had the thrillingly picaresque name of Jessie Lightfoot. She stayed on board until her death.

When times were hard, Nanny Lightfoot became Nanny Lightfingers and utilized her shoplifting skills to put food on the table. She would also vet the propositions Bacon received from ads offering his services as a “gentlemen’s companion,” which means exactly what you think. However, she was an avid advocate of capital punishment and “longed for the day when the gibbet would be re-erected at Marble Arch, with the Duchess of Windsor as the first public enemy to be hanged, drawn and quartered there.”

Hanged, drawn and quartered? Sounds like something you might see in a Bacon painting.

Bacon, Sweeney Agonistes,1967

Here Comes the Judge

Artists are sometimes judged by their influence on other artists. Unfortunately, we would be hard put to come up with any painter influenced by Bacon — except perhaps his friend, the older and very dreary Graham Sutherland. That artist’s signature thorn-forms were clearly a reference to you-know-whose crown of thorns, but only under Bacon’s influence did Sutherland attempt a crucifixion or two.

Brit critic David Sylvester’s book of edited interviews (1975) reveals how dumb Bacon actually was, or at least pretended to be. He was certainly smarmy. And if he was trying to put himself across as an Abstract Expressionist who hated abstraction, or as a Surrealist, he failed. Sir Roland Penrose, when he was only Roland Penrose, rejected Bacon for his 1936 International Survey of Surrealism for being “insufficiently surreal.”

You can catch two segments of the actual interviews on YouTube, notable now for the leading questions continually proffered by Mr. Sylvester. With a friend like that — artists beware of critics with microphones — you don’t need an enemy.

On the other hand, now we can certainly say that Bacon influenced the face of cinema.

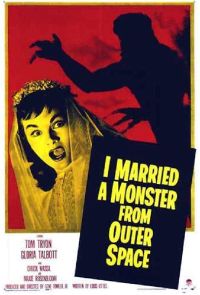

I Married a Queer From Outer Space

Desperate for something to watch, I recently turned to TCM on Demand and found, of all things, I Married a Monster From Outer Space, Gene Fowler Jr.’s crazed 1958 exercise in paranoia, with art direction by Henry Bumstead and Hal Pereira. I could not believe my eyes.

The movie’s about a takeover of small-town husbands — one by one — by an alien all-male race that needs to find females to reproduce. It is really about gay men taking over the world. The “husbands” sulk and brood, bond with each other, and disappear in the middle of the night to go on long walks. But the “real” men — breeders who have sired children and who own rifles and hunting dogs — get them in the end.

Periodically flashes of lightning reveal the real faces of the alien husbands, who are without emotion and seem not to be able to impregnate their Westinghouse brides. This is how we know it is not just the zombie played by Tom Tryon who is a monster, but also several others, including the cops and a telegraph operator who stops a cable to the FBI. Do their real faces remind you of a certain artist’s Picasso rip-offs?

Which face is the artwork?

[Scroll to end for answer.]

In spite of the socially and family-induced self-loathing, his acting out and acting up, and his profligate ways, Bacon has a life story and psychology (if you dare call it that) that are vastly more interesting and more entertaining than his ghoulish illustrations now on view at the Metropolitan. Although torture never goes out of fashion — thanks to Cheney and Bush — Bacon’s dated specimens of beef, beefcake, and blood are at best paint-smeared, writhing footnotes to The Age of Anxiety. He would have loved waterboarding but have used it as titillation, not condemnation, or as just another metaphor.

Wouldn’t we rather see a Leon Golub show at the Met?

Answer to photo quiz:

Left: Tom Tryon with alien face, I Married a Monster From Outer Space, art direction by Henry Bumstead and Hal Pereira.

Right: Francis Bacon: Three Studies for a Self-Portrait (detail).

Never miss an Artopia installment! For an Automatic Artopia Alert,

contact: perreault@aol.com