The New Art History

Blessed with hindsight, it is now quite clear that in the late ’60s the big question in art was how to include content without compromising abstraction. Pop was too popular, offering the spectacle that the critique far too easily became that which was being attacked. Celebration during the Vietnam War was untenable.

Yet immediate art-world forefathers (women did not yet count) were divided, in more ways than one. A separation between beliefs and actions is a kind of moral schizophrenia. Art and content, particularly political content, were sealed off from each other. Artist elders with a social conscience, such as Ad Reinhardt, maintained a kind of Berlin wall between their political beliefs and their art, maintaining the hard-won right to make art that was art-about-art, that was pure, that was totally abstract — descending from Mondrian and Kandinsky, but spared from theosophy. If your art had no recognizable imagery, you could not be held accountable for political mistakes or be hounded by some latter-day Stalin. Or Joe McCarthy.

The one thing to say about art is that it is one thing. Art is art-as-art and everything else is everything else. Art-as-art is nothing but art. Art is not what is not art….

Words in art are words.

Letters in art are letters.

Writing in art is writing.

Messages in art are not messages.

from Art as Art: The Selected Writings of Ad Reinhardt, Univ. of Calif. Press, 1973.

The logic escapes me, but behavior based on fear is never logical. We honor Reinhardt’s all-black paintings, but rereading his writings makes it clear that all of his writings were self-promotion: I, Ad Reinhardt, am the only artist. My all-black paintings are the only possible art.

And Reinhardt’s “dogmas” could now be mistaken for the formalism of his political opposite Clement Greenberg at his worst and most unforgiving. One of the best things you can say about Reinhardt is that Greenberg hated his work. And he apparently did not like the paintings of my personal hero Barnett Newman, a far greater artist who, unlike Reinhardt, was not afraid of form or spirit and who in 1933 ran for mayor of New York. He was an Artopian ahead of his time. The platform of his Writers-Artists ticket was for: a municipal art gallery, sidewalk cafes, city opera, and playgrounds for adults. He also, by the way, in 1954 sued Reinhardt for libel, for classifying him as a huckster, among other things, in that artist’s very silly article in the Collage Art Journal.

And then a little bit later, along came Sol LeWitt — who Earth Artist Robert Smithson privately referred to as Saint Sol. LeWitt was a great artist and he was also a genuine liberal and believed in all the right things. His wall drawings, nevertheless, have absolutely no political or social content.

In short, for many serious artists, representational imagery was to be avoided at all cost: It smelled of the academy, of boring Social Realism, and of Pop.

Enter Conceptual Art, which tried to replace recognizable imagery and Forefather Abstraction with words. You could have your cake and eat it. Words were not representational in the same way images of grandma and grandpa and all their sandy-haired descendents sitting down to a Thanksgiving dinner were; not representational like murals showing the triumph of the workers or — headshots of movie stars. You could even say words that were abstract, since they did not look at all like what they referred to. Yet the advantage over squares and monochromes is that words can be read; words allow content without depiction.

Did the use of words really solve the problem? Well, the history of art is based upon moves that are never as clear and uncompromised as some would like. And although we do not believe in art progress, sometimes a sidestep is indeed a step forward.

I don’t think Conceptual Art wiped out either abstract or representational art, any more than photography did. And it certainly did not wipe out poetry. If there is any poetry in Conceptual Art, it is of the same order as the poetry that painting and sculpture have sometimes attained: a poetry that has nothing to do with words. Nevertheless, Conceptual Art — coming directly out of Minimalism in painting and sculpture — was a great opening up for art just beginning to be assessed, now that the puritanical, macho, monotonous aspects of both Minimalism and Conceptualism have faded.

Bear in mind however that a lot of what still passes for Conceptualism is really Dada Entertainment — of which I am fond — compared to the tough stuff I also like. I try not to confuse the two. Because there was recently an exhibition of his work (called Im [sic] Full of Byars) at the Kunstmuseum in Bern, which will travel to London and Detroit, James Lee Byars comes to mind as an example of the former. Yet his gold-leaf room and his sphere made out of roses really hold up. And I remember a performance of his at the Architectural League in New York, in which (dressed in flowing red cloth and his trademark hat) he just sat there and answered or entertained any question that was asked. Sometimes time edits out all the bad stuff. Well, maybe not…

The good thing and the bad thing about Hard Line Conceptualism is that it is not charming. After the ’60s, Minimalism and Conceptualism seemed to have left a big void that needed to be filled. Pluralism stepped in.

Much Ado About Nothing

To some, Conceptual Art is one big nothing. How big is nothing? Is nothing something? In the previous Artopia screed we tried to address that void, artwise. The question today, inspired by the new Robert Barry exhibition, is: What are numbers? Or how much is too much? Or better yet, does multiplicity equal infinity? Does infinity equal eternity?

Philosophy, perhaps rightly, no longer cares. These kinds of questions are medieval. But we live in neo-medieval times. Physics, mathematics, and theology converge. We not only exist in a world of objects, a world of persons, and a world of words, we also exist in an equally mysterious world of numbers. We now hear trillions of dollars spoken of without a pause. But who can picture a trillion dollars for this or that rescue plan? These trillions are needed, but what do they look like? How much do they weigh?

Money is just another form of information. It is one big nothing.

As we approach vast numbers, they disappear. In all worlds, close examination leads to erasure. How odd. The more you look, the less you see. Some numbers are so big they surpass all understanding. They are abstract and vaguely symbolic. Measurement cannot itself be measured.

At the root of number is paradox. Please remember that Lewis Carroll was a mathematician and quite advanced for his time. At some point, multiplicity beyond understanding or sense – is another Void. The invention of zero was more important than the invention of the wheel.

When I first read of Barry’s One Billion Colored Dots — now on view at Specific Object (601 W. 26th Street, floor 2M, room M265; M-F, to April 24) — I imagined books full of gummed dots, perhaps of various colors, but definitely red ones. Red dots on walls next to paintings or on wall labels were once commonly used to denote that the artwork in question had been sold.

Scooped again. Which, I thought, was what I get for being a secret artist. In the ’60s I filled two blank books with thousands upon thousands of red dots, page after page. In one book, the dots were placed randomly all over each page; in the other, they were in neat rows.

The 601 West 26th location is a gigantic, multiuse building on the western border of Chelsea. The lobby looks uptown, but once you pass security and get off the elevator, you are in a kind of grungy, industrial warehouse time-warp. The door to Specific Object could be guarding deep storage of fur coats or ancient computer equipment. But never fear, once inside, the nostalgia abates and the modest exhibition room is pristine.

Fortunately, Barry’s books are not at all like mine. My books were about art commerce (at least on the surface); his dot books, for starters, are about “number” and a certain self-referring opaqueness.

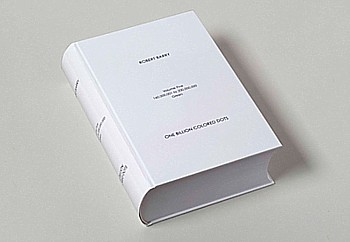

For the current project — which slyly approaches the sublime — he has expanded a piece he made in 1968 for Conceptual Art entrepreneur Seth Sieglaub’s Carl Andre/Robert Barry/ Douglas Huebler/Joseph Kosuth/Sol LeWitt/Robert Morris/Lawrence Weiner, usually referred to as “The Xerox Book.” Each of the artists in this tightly curated list was allotted 25 pages. Barry, to the tune of 40,000 dots per page, produced One Million Dots.

Then, as I found from the online essay by LINK Frédéric Paul, in 1971 he created the first One Billion Dots: a single set of 25 volumes. Now what’s offered is a new edition that consists of 30 sets of 25 volumes of dots. Here’s a precise description offered by the Specific Object/David Platzker Gallery:

Indent:

In this project Specific Object presents a new edition by Robert Barry consisting of twenty-five volumes — each volume composed of 2,000 printed pages, each page with 40,000 dots, each volume containing 40,000,000 dots, thus presenting 1,000,000,000,000 dots through the course of the 25 volumes. Additionally, each volume has been printed in a single color. The edition contains one volume in each of the following colors: red, blue, orange, violet, green, yellow, maroon, blue green, light green, ochre, light purple, light grey, dark blue, pink, yellow green, purple, light orange, red violet, light yellow, silver, light blue, grey, gold, white, and black. Over the span of the twenty-five volumes one billion colored dots are presented.

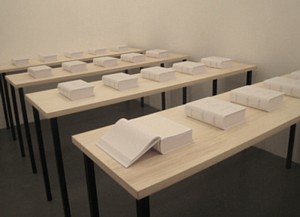

The presentation is appropriately immaculate. One book is open and white gloves are supplied. And since I am familiar with Barry’s work, I know that there will not be any surprises. No pornographic inserts. No sudden change in the size of the dots. For as he himself once stated, “I always do what I say I’m going to do.”

I was and am relieved. On another level, I once asked myself, “I always do what I say I’m going to do? What fun is that?” But we soon learned, and learn all over again, that Conceptual Art on its highest level is not about fun.

Mathematical tablet from Uruk, late third or early second century BC, containing one of the earliest known instances of the Babylonian zero; Louvre, AO 6484 side B.

Zeroing in on Art

For obvious reasons, I am more interested in zero than in all the other numbers. Well, maybe not for such obvious reasons.

Zero, we are taught, began in Babylon, c. 350 BB; it was also later invented

independently by the Maya, c. 300 CE.Europe didn’t have a clue until around the 12th century, when zero was appropriated from the Arabs. The word zero, we are further informed, comes from the Arabic sifr, which also yielded cipher — a meaning not unrelated to zero. “Zero” in Arabic is a dot.

The word zero, however, has at least two separate meanings. It is both a place-marker, allowing easier counting and arithmetic than other systems, and, more mysteriously, a number in itself.

In terms of the latter, the Ancient Greeks would have nothing to do with it

Because, they “reasoned,” how could a number be nothing? Confusing numbers with things, however, is just as bad a confusing words with things. Silly Greeks.They even had trouble solving Zeno’s paradoxes, didn’t they?

The Indian subcontinent also beat out Europe in figuring out zero.

In about 850 A.D. Mahavir, a Hindu mathematician, wrote in his book, Ganita-Sara-Sahgraha (The Compendium of Calculation): “A number multiplied by zero is zero, and that number remains unchanged which is divided by, added to, or diminished by zero.”

Today we agree on most of what he says. We can add or subtract zero to a number and just get back that number. When we multiply a number by zero we get zero. The division by zero is where we disagree. Today division by zero is undefined. Reference.

The paradox we most like is that one needs zeros or nothings or voids to express big quantities like one billion (1,000,000,000) in other than words.

Barry, Douglas Heubler, Joseph Kosuth, Lawrence Weiner, c. 1968

It’s Only Words

Barry belongs to the small group of Conceptual Art pioneers — most, I would venture to guess, influenced by painter Reinhardt’s gnomic pronouncements. These were so ultra-formalist that they opened the way for a Dada antiformalist reissue with a political, often neo-Marxist edge.

Like Lawrence Weiner (who almost patented the move), Barry has produced word-works on gallery walls. Isn’t it time for a survey of word art? Partial list: Barry, Heubler, Jenny Holzer, On Kawara, Kosuth, Barbara Kruger, Weiner.

But Barry’s best works now seem to be the 1969 closed galleries — rather than the 1970 Some places to which we can come, and for a while “be free to think about what we are going to do (Marcuse) recently reinstated in “Void” at the Pompidou — the inert gas series in which he released rare gases into the atmosphere; and, of course, the dots.

Is his art as scattered or as “free” as it sometimes appears? Has Barry successfully avoided a marketable identity, a product line? Is there a difference between focus and product, between identity and brand?

Does it still hold true that the best art provides questions, not answers?

FOR AN AUTOMATIC E-MAIL ALERT WITH EACH NEW ESSAY

CONTACT: Perreault@aol.com