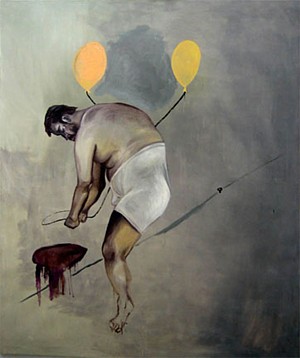

Martin Kippenberger: The Happy End of Franz Kafka’s “Amerika,” 1994.

How German Is It?

I have a problem with Martin Kippenberger. Not personally; after all, I never met him, but I have a problem with his work. It is not anything fancy as might be suggested by the awkward subtitle of the current festival at MoMA: “Martin Kippenberger: The Problem Perspective” (to May 11). If an art history graduate student were to use this phrase and I were the professor (which I have been), I would make the criminal leave the class, the university, the universe.

So, where to begin?

The best thing and simultaneously the worst thing one can say about the huge amount of “art” Kippenberger (1953-1997) left behind is that it is all so ’80s. In order to really “get it,” you had to be there, which does not bode well for immortality, does it? We like art that is anchored to its time and its culture, but if that is all it is, then we do not really cherish it. It has no — perish the unfashionable thought –transcendence. In Artopia, the transcendent and the quotidian are not in opposition. In fact, they can be exactly the same.

Furthermore, to get it off my chest right at the beginning, this once again fashionable artist left no oeuvre. He left jigsaw-puzzle pieces that, even when you put them together, won’t add up to a pretty picture, an ugly picture, or any picture at all.

But I have to confess that the ’80s was not a period I liked. The new art was all supposed to be post-Postminimalism or postmodern, and most of it was pretty dumb. The market reigned, most critics cow-towed, capitulated; went to dinner, dining on the fatted calf.

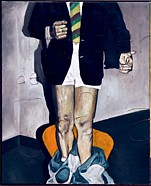

Kippenberger, Disco Bomb, 1989

Surely, art about art was nothing new. I had been teaching that

aspect of art since the ’60s. What was different about the “bad painting” and most of the lightweight lifting of the period was that art about art was all most of the art was about. To me it looked academic. It was quotation art, It was footnote art. And that still holds true for many Big Names from the ’80s.

There was no peeling away of the given. There was no attack on the bourgeois. The art world had become the bourgeoisie. Artists had lost their calling. Art was product. The practical aspects of the art enterprise became the center and not just the unavoidable support structure. The clever or their clever apologists claimed that the various product lines were critical of the very thing that made them marketable. But never before had such tepid irony been put to such tepid use.

At least Kippenberger was rambunctious, was vulgar. At least Kippenberger was sometimes abject, forlorn, ridiculous. As a failed, fancied or would-be actor, he was so bad at acting that his attempt at filling the role of artist was transparently a kind of silly — sometimes petulant, sometimes hilarious — form of acting-out. The products he produced in his art “factory” are not art; they are props. He invented Prop Art

.

.

No one wanted so much to be bad as poor Kippenberger, hence Martin, Into the Corner, You Should Be Ashamed of Yourself (1989), a 3-D “self-portrait” of the bad boy forced to stand in a corner, oh, just hoping to be spanked. As an example of failure — which, oddly, is its strength — it is not much different from the painted-to-order 1981 photorealist piece of junk showing Kippenberger posing and looking much like his idol, screen-star Helmet Berger, on an abandoned sofa in a New York street from the series called “Dear Painter, Paint for Me.”

Being an artist is a way of composing yourself. Or inventing yourself. Uncle Andy knew that, and much earlier. In Artopia we see Warhol’s silkscreen paintings of Marilyn, Elvis, Troy, Liza, Jackie not as evidence of a poor boy from Pittsburgh trying to shine up to the stars, but as delicious, malicious deviousness. He was creating a context, a platform, for the introduction of Andy Superstar, Andy Warhola’s greatest creation. With his index finger held up to his lip – like Redon’s Silence? – Andy is the triumph of ambition over false modesty. What was the secret he eternally asks us not to share?

Kippenberger: With the Best Will in the World I Can’t See a Swastika, 1984

The Secret of Success

To his credit, Kippenberger apparently was also out to get at or to Oedipize some of the most pompous artists who have ever stalked the earth. Here we have to time-trip to the ’80s, in Germany. Yes, Germany. For Kippenberger was about as German — at least as post-Checkpoint Charlie German — as one can get. I doubt that he had much love for the great Joseph Beuys, now safely enshrined in Artopia Valhalla. Kippenberger’s satires of the role of the artist in Western society — substituting the actor and the buffoon for the martyr and the saint — are aimed at The Master Himself. Beuys’s multivalent performances — such as the remarkable How to Explain Art to a Dead Hare — are transformed into Kippenberger babbling to himself: “If everything is good, then nothing is good anymore.”

So what.

Don’t be such a baby.

Kippenberger is the anti-Beuys. His Germany is not the Germany of Siegfried but the Germany of beer and bratwurst. And yet …. What are we to make of Kippenberger’s backhanded loyalty to the cult of the artist? Misplaced Romanticism? Deutsche Punk?

No. In the hands of Kippenberger (or those of his many studio assistants), the lesser fish are much more efficiently speared. I mean, horror of horrors, the unholy three: Sigmar Polke, Gerhard Richter, and Anselm Kiefer. This loathsome trinity performed the same function that David Salle and his like performed in the U.S. They returned art to painting — safe, dreary, saleable “painting.” They delivered the goods. But with just the right edge. Naughty, but supremely digestible.

What is the connection between pastry and pastiche?

Goodbye to performance art, non-object conceptualism and even to Earth Art. Collectors must have normal art for their investment portfolios.

How do you stick it to Gerhard Richter? Well, first you hire someone to make a photorealist painting of two tipsy lads walking down a busy street in broad daylight. But if that is not good enough or obvious enough, you buy one of Richter’s small, very boring abstractions — just as boring as his photorealist paintings — put legs on it to turn it into a coffee table, and then sell this assisted readymade for less than you paid for the Richter itself.

How do you answer the pompous straw paintings of Anselm Kiefer? You cover a much admired, American-made Ford Capri with brown paint and oat flakes, hence Capri by Night, 1982.

How do you take a poke at Sigmar Polke? You make your own paintings of overlapping banal imagery.

Is Kippenberger any better then Polke/Richter/Kiefer? Only a smidgeon. What saved him was his lack of talent.

My Kippenberger problem is one of gilt by opposition. What does it mean when pretty much all you can say about an artist is that at least he is not like X, Y, or Z? Which would be like saying that Jasper Johns is great because at least he is not Robert Motherwell or Helen Frankenthaler or Jules Olitski.

Kippenberger was severely limited. He does not appear to have been particularly smart or good at making things.

Because of this, he was both a literal and a psychological Bricoleur – pace Claude Levis-Strauss — rather than an Engineer. That I have to use the terms of that recherché dualist is telling.

Kippy took things from here and there: ideas, old pieces of furniture, personae. And because of his lack of talent he was able to allow emotions normally forbidden to the art of the period: sadness, childishness, and, yes, despair. Because he had no talent, he had to steal from everyone, parody everyone, and use gross humor to make his way.

On top of this, it now looks like he was also out to get Warhol, Sol LeWitt, and, best of all, Pablo Picasso.

With his endless production of posters, books, and “artworks” of all kinds, our Bad Puppy (unlike his Bad Yuppie American counterparts) aimed to out-produce dear old Andy. With his scary and ultimately very moving Kafka piece — The Happy End of Franz Kafka’s “Amerika” (1994) — he was out to skewer the theme-and-variation investigations of Sol LeWitt. See here LeWitt’s Three-Part Variations on Three Different Kinds of Cubes (1967-71), truly an Artopia favorite. Instead of cubes, we get Kippenberger’s variations of the interview table with two opposing chairs — thus revealing the Kafka underpinnings of some of the most beautiful work produced in the generation that came before.

The scene constructed by Kippy Inc. is a forlorn employment office for immigrants, furnished from some Salvation Army outlet in hell. Nowadays, the downsized (i.e. the suddenly fired) can apply for unemployment insurance online — using public-access computers in libraries or their Blackberries, but they are not spared cabin fever.

Celestial justice has deemed that now every American must feel like an immigrant again, as homeless stockbrokers and bankers wander with their ever-younger replacement wives and their mall-rat broods from one broken-open, abandoned McMansion to the next, dining out on rusty lettuce left outside in garbage cans behind fast-food joints, charging up their cellphones and portable computers (if they still have them) in the few unprotected electric sockets in public places. They go to Long Island railroad stations in their suits not to commute, but to recharge their batteries. Greed was their creed. And now they wait to be interviewed in the soccer field of Kippenberger’s The Happy End of Franz Kafka’s “Amerika.”

And the late Kippenberger self-portraits? Mr. Gross shows himself not as the movie-star wannabe of his youth, but as a bloated Picasso. And only in his 40s. Those diaper-like underpants, once worn by Picasso and appropriated by Crazy Uncle Kip, will never go away, which is a lesson for us all. What was Pablo thinking when he allowed himself to be photographed wearing these abominations? And what was Kippenberger thinking? There is both fear and glory. We now like our artists trim and well-disciplined. Kippenberger was neither. Duchamp would never allowed himself to be photographed in droopy drawers.

We also like our artists sober. I wish I could say that Kippenberger aptly illustrated the Blake adage — and official Artopia motto —that the road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom. No such luck. Known for singing boisterously and dropping his pants at the drop of a hat, Kippenberger, who died at 44, was not about self-possession or wisdom. He could hardly stand up.

Kippenberger: (detail) Down with Inflation, 1984

NEVER MISS AN ENTRY AGAIN! FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT, NOTIFY perreault@aol.com

|