What The Art World Was

This is an odd, but fascinating book. Look Up: The Life and Art of Sacha Kolin by Lisa Thaler (Midmarch Arts Press, 2008) is the tale of an artist written not by an art historian, but by a genealogist and/or, as the author seems to prefer, a “family historian” using her professional tools … and then some. In an afterword, Thaler discloses she was drawn to Kolin’s story for three reasons:

I was curious about the children of the so-called illustrious immigrants. Little has been written about this younger generation of refugees. I was surprised that a prolific, exhibiting artist could have so quickly fallen into obscurity. And I was challenged by the research constraints and saw potential for innovations in my field. Could I read a painting the way I read a birth certificate?

This is the story of an “almost,” an also-ran, a could-have-been — yes, a failure — who, according to many who knew her, was energetic and charming. For an art historian, art critic, or curator there would be no cash value or prestige in writing about a failed artist. We are, therefore, often denied the nitty-gritty taste of the real lives of artists — most of whom are not superstars. Here we get the taste — the bad taste.

If Look Up were to be made into a movie, it would show Kolin’s art in 1981 being tossed into a dumpster outside an expensive Soho loft, then cut to author Thaler discovering a painting by Kolin in an art auction, falling in love with it, and finding out that she and a collector cousin now had Kolin in common.

Books about artists are either promotional tomes, often with serious and brilliant essays by noted art critics and art historians, or at the not-so-distant other end of the commercial spectrum, pop entertainments of the Lust for Life variety.

Concerning the latter, who now wants to read about the lives of artists when most are businessmen or -women? It’s not entertaining to read about a visual arts CEO and his (mostly his) struggle with auction houses, dealers, and tax accountants.

But can you imagine — even if you like his art, which I do — a novelized life of Damien Hirst? Art has, alas, been thoroughly demythologized.

Look Up is a window into an art world that no longer exists. I don’t think I ever met Sacha Kolin, and I am glad of that. But I could have met her. It’s a Facebook (or as I call it, Facebutt) Effect: we had a few “friends” in common, and many more friends of friends. Far too many friends of friends. The author and I also overlap. Although she lives in Chicago, she studied contemporary art at Hunter College with Mary Miss, a sculptor I know.

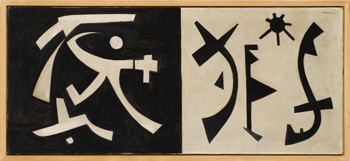

Sacha Kolin, Departure, 1954

Sacha Zelig

I think of Look Up as a kind of “found” novel. I would have loved to have invented both the subject (Kolin, pronounced ko-LEEN) and the author of record. Because the writing style is lean, the text could pass for latter-day modernism. It is just awkward enough in places to make the whole enterprise ring true. Everything is presented; very little is interpreted. What lesson are we being taught, if any? Is this a cautionary tale? Whatever happened to Truman Capote’s Non-Fiction Novel genre?

The “author” — far too obsessed with Kolin’s Jewish roots — is, while certainly not the main character, at least the dispassionate voiceover. Yes, Kolin, born in Paris of Ukrainian Jewish parents, was raised in Austria, where the family had to escape from the Nazis back to Paris, from where they had to escape again, not to Argentina with other relatives but to New York. New York of the Great Depression.

But the Kolins, Thaler admits — undercutting her personal theme — were assimilated and seemed not to have retained even cultural markers. Daddy Kolin was an inventor of some success, and with wife and unmarried 25-year-old daughter Sacha — our heroine — in tow, was able to afford various palatial Upper West Side apartments, at least up to a point. These digs no doubt had doormen and views of the Hudson.

In Austria, Daddy Kolin had developed “the first contra-rotating propellers in 1911, the first sonic tip speed propellers … and the first airplane capable of vertical take off” and then in the ’20s developed sorely needed, and very profitable, “grain sorting, cleaning and crushing machines.” In the U.S. after the war he designed “turbo-pumps and inducers for rocket engines.”

Because she had studied at the Weiner Kustgewerbeschule and the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, Kolin claimed membership in the Vienna Secession. In Paris, she studied with Rodin’s stone-carver.

And fresh to New York in 1936, brash Kolin joined every artist association it was possible to join. And pushed, pushed, pushed. She gave dinner parties and bought her clothes from a high-end clothing shop on Madison Avenue.

There was no stopping her. After World War II, she plied her ambition in Provincetown, Massachusetts, then a thriving summer art colony. The names ring a bell: she was a member of the Gallery 256 co-op along with Will Barnet and Louise Nevelson. Thaler found Franz Kline listed in Kolin’s P-town address book.

Shape-shifting with every art-world tide, she showed at Guild Hall in East Hampton and then in Hampton Bays at David Burliuk’s short-lived art gallery. Burliuk was the illustrious Ukrainian father of Japanese Futurism.

Although Kolin never embraced Abstract Expressionism or Pop, she had an Op Art moment. And then, at the height of her “career” — when she had transformed herself into a Park Place/Primary Structures minimalist — she showed at the Max Hutchinson Gallery in 1978. I knew some of that gang. And then too she bothered Andy Warhol and seems to have been actually friends with the notorious Ray Johnson of Mail Art infamy, who sometimes bothered me.

Kolin, Night and Day, 1956

The Dark Side of the Heroic

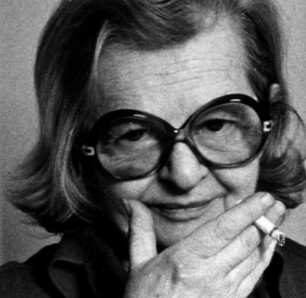

Kolin was short and flamboyant, entertaining. She never lost her Middle European accent. Fearing dentists, later in life she was toothless but could still eat corn on the cob. Strong gums, indeed. And she was a chain-smoker, as were so many in the deep, dark past.

She stuck with Daddy and, after the early ’60s, with her signature dogs, which were salukis – a kind of ancient Arabic greyhound. Her dogs were with her until the end. Although she had often espoused help for the homeless, she and Daddy and the dogs at one point were homeless and lived on the proverbial park bench and then — to add a note of classy originality — in a rented car, parked on a side street.

But this was not the end of her ups and downs. Daddy, who just went on and on and always wore a suit and tie, although increasingly rumpled, finally got stored away in a nursing home, where he delivered memoranda on how to improve efficiency.

As to Sacha herself, she kept plugging away, building up enormous bills at Dean & Deluca, the ritzy Soho food emporium. No matter how poor she was on any particular day — waiting, waiting, telephoning over and over again, waiting for some art deal to come through, or some dinner party — she never took the subway, but required cabs.

How did she survive? She was relentless, some say ruthless. She had confidence, as did the riverboat con men in Herman Melville’s great 19th-century “postmodern” novel, The Confidence-Man, written about the time the term was first used.

She never held down a job. She never taught at some god-forsaken art school in Podunk. Her art was her only work. She traded art — which she promoted as being far more valuable than it actually was — for her rent, her clothes, her food, her medical attention. She was the queen of networking and the museum-donation triad: A donor in hand, she would persuade a museum director (often installed in a university museum) to agree to acquire one of her works — a drawing, a painting, and eventually big-time Primary Structures for outside. She would have already “sold” the work to the collector at a bargain price, and then the “collector” would donate the work and be able to deduct the so-called market value of the piece from his taxes. Then, as now, artists were not allowed to deduct more than the cost of materials — which, by the way, really needs to be changed.

This triad scam came into effect in the late ’60s. And it did result in museums acquiring a lot of work they normally would not have been able to afford. So perhaps it was an indirect subsidy to museums (and in some way to galleries and artists, too). Direct subsidy, as through the newly founded National Endowment for the Arts, was soon quite iffy, given the rednecks in Congress and the generally anti-art, anti-artist prejudice of the unconverted. The latter probably realized unconsciously that art was a religion, and we have always been for the separation of church and state, right?

But the museums were happy. Although they may have been misguided by how well Kolin looked on paper, as it were, they expanded their “permanent” collections or acquired a big-time public marker for their lawns. The artist was happy. She made the sale and she was in yet another museum collection. When I briefly became the curator of the Everson Museum in Syracuse, New York, there was indeed a big Kolin in front of I. M. Pei’s leaky cubic building. Flat roofs in snow country? Well, they looked good. And Kolin’s sculpture seemed perfect, too.

Kolin (and unidentified man) in front of Sky #1, 1973, in front of the Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse.

Lost Horizons?

Oh, lost world! Kolin’s world was not the semicorporate art world we now know. Go to art school; get a degree; show at Gagosian. Or die.

In contrast, her world still reeked of the Cedar Bar — which everyone knew was not on Cedar Street but on University Place, walking distance from all the galleries on East 10th Street. It was not a place for women. Kolin herself complained about how women artists were treated and how they were often dismissed by male critics, male curators, male museum directors. She herself, however, had no women friends.

Art had not yet been demythologized. Art was still a belief system.

But why was she a failure? Her paintings were not all that original. She was always one step behind. And cheerful whimsy doesn’t really have much staying power. Her sculptures done later on in life were much better.

Never had a retrospective in a New York museum. Never had an Abrams tome about her work. Although she had reviews in Art News and other magazines, she was never championed by a high-profile critic.

Look Up (titled after one of her paintings) is the life-of-an-artist as nightmare. And if you are foolish enough to identify with her, you will be sorry. Although she thought of herself merely as an exile, behind her awfully cheerful Miro-esque paintings, behind her leisurely suppers and elegant dogs, was the soul of a con artist.

After her beloved Daddy — let’s not go there! — lost his earning power, which was years after he had been investigated by the F.B.I. for espionage, they lived by her wits and by barter. The check is in the mail, the rubber check. But in the meantime, Dear Landlord, why not take something much more valuable in lieu of stupid money: Here is a painting or a sculpture worth thousands.

Kolin with unidentified sculpture, c. 1973?

Multiple Endings

So you think having your art in the permanent collection of an art museum will guarantee immorality? Think again. The author reveals that “Nine out of 20 of the museums cited in her 1973 Everson exhibition catalogue have deaccessed all their Kolin holdings.”

And then there is the image of the curb-side Soho dumpster piled with her stuff at life’s end: paintings, drawings, cardboard maquettes for sculptures.

If this book were to be made into a movie, we would have to have a better ending. Mine would be that New York’s Ukrainian Museum would give her a retrospective. After all, both her mother and father came from the Ukraine. Or are Jews from the Ukraine somehow not Ukrainian? Failing that, although she was totally assimilated, there’s always the Jewish Museum. And someone in the New York Times would proclaim her a great rediscovery.

But as Graham Greene wrote in his now all too appropriate story “Across the Bridge” (about a con-man tycoon on the lam whose only friend is a stray dog), “Death doesn’t change comedy into tragedy.”

So, how is this for an ending? According to an informant, after refusing treatment for ovarian cancer, on her death bed she had the final word.

“What can I do for you?” The friend asked. “Out of the corner of her mouth, she said, ‘Lobster.’ So I bought a whole lobster just down the street. Sacha devoured it.”

ALTHOUGH PAST ESSAYS CAN BE ACCESSED BY CLICKING ON “ARCHIVE” TO THE RIGHT (SCROLLING DOWN REVEALS SUBJECTS), NEVER MISS AN ARTOPIA ESSAY AGAIN!

FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT CONTACT: perreault@aol.com