Agnes Denes: Photograph of Wheatfield — A Confrontation

What Do Women Want?

In Artopia, art is gender-neutral. This does not mean we deny that women, for one reason or another, cannot offer art that deals with what are sometimes called “women’s issues.” And men can deal with “women’s issues” too, or for that matter, topics deemed male or manly by our weird little culture: sports, war, guns and cars (as if women were immune to these). Nor do we need to ban particularly womanly subjects such as birth or menopause. In fact, participant perspectives are always worth having, as I think Judy Chicago proved ages ago, with both her Dinner Party and The Birth Project.

The point is that unless you are ridiculous enough to hold to the old-fashioned notion that art itself is gender-specific (i.e., specific to males), it behooves us to look at the art itself. Some men have mothers, wives, daughters and want to know what goes on inside of their heads. If we need art at all — and we do, now more than ever — we cannot afford to avoid more than half of the art produced, simply because men have not produced it.

Statistically, more male than female artists are famous, but this is merely documentation of oppression, or at best the sociological facts. In our culture, little girls are expected to be “artistic.” In spite of this, some of them go on to art school and actually develop the notion they can be full-fledged culturistadors, on a par with Michelangelo and van Gogh.

So the short answer to my question is that women artists want to be treated fairly as artists. Women want success.

Let us leave aside for the moment the definition of success that equates it with commerce. Even what we might call spiritual success in art is dependent upon support systems and supportive persons, but at this late date, when feminism is thought to have won out, there are few fully developed support systems and support persons for women artists, even among women. Show me the art dealer who represents more than one or two women artists; show me the art critic, male or female, who writes about more than one or two female art stars; show me the collector who puts her money where her gender is.

So…

This fall I have been reluctant to venture into Chelsea, which seems more and more the art world’s red-light district. Is it because I am afraid I will be knocked down by bodies falling out of penthouses? Oh, I’m sorry that was last week, when the stock market was still bottoming out and real estate and art sales were being left in the lurch. The reason I have been avoiding Chelsea is certainly not because I think auction houses are more important — which is the insouciant thing to say. Nor is it because I spend all my time hanging out in museums, which as everyone knows, here and abroad are the handmaidens of the blue-chip galleries. This is not new; it is simply more transparent.

Instead, I am drawn to the unexpected.

Women in the Driver’s Seat

For instance, who would have thought – way back when – that an all-woman co-op gallery would outlast most commercial gallery startups. A.I.R. is celebrating its 36th year, with the three-part “A.I.R. Gallery: The History Show.” A.I.R. documents, now in the NYU library archive (70 Washington Square South, through December 12) are neatly on display on the third floor of Philip Johnson’s oppressive Bobst Library through December 12.

Be forewarned, you must request a temporary pass, but that’s easy enough. On your way to Special Collections, the exhibition starts as a long hallway, but, fear not, a turn at the end opens up into a real room with cases of A.I.R. documents. Every announcement ever mailed. Photos, programs.

A two-part exhibition of actual artworks is also on view in DUMBO, where A.I.R. is now ensconced (111 Front Street, Brooklyn; Part One to November 1, Part Two Nov. 6-29). It is in one of those big old warehouse buildings, the third floor of which is dedicated to modest but chic gallery spaces. The galleries are there to provide high-end real estate identity and customers for the double-latte outlets on the strip below. No, I’m only joking. Chelsea is too expensive. And you don’t even have to say DUMBO is Brooklyn. You know you are in Brooklyn because you can glimpse Manhattan, if you peer down one of the narrow streets. It is not that far away. Up and down the street I see nannies pushing expensive baby carriages. When I look up, I see penthouses. And I suppose even here the bodies will be falling to the pavement unless we stop all of these automatic stock transactions, little-boy panics and out-of-control deals that even the dealers don’t quite understand. What exactly are “credit default swaps” and “collateralized high-rated or BBB tranches”? And you used to think Dada was hard to define.

Just in case you wanted to know, DUMBO was not named after the Disney elephant.

Does anyone remember that SoHo means “south of Houston” or that TriBeCa means “triangle below Canal”? It used to be that if you could coin an acronym for any old neighbor and move the real estate.

To invent a new parlor game, DUMBO does not mean:

DANGEROUS U-TURNS MAKE BROOKLYN ODD,

DEAD UNCLES MEET BROKEN OPALS,

or DUST UPON MY BEAUTIFUL OPPORTUNITIES.

Anymore than TriBeCa means TRIUMPHANT BECKONING OF CARAVANS.

Because of the Manhattan Bridge Overpass and the Manhattan Bridge itself –glimpsed between film noir buildings on film noir streets — DUMBO (Down Under Manhattan Bridge Overpass) looks like a movie set, even on a sweaty October afternoon. The wheels-on-metal traffic overhead adds punch to the Manhattan Bridge harp.

Here’s some history: The A.I.R. all-woman gallery was founded by Barbara Zucker and Susan Williams, later joined by a host of others, and opened its doors in what was once called the Cast Iron District in 1972, before SoHo became the going term. “A.I.R.” stands for the A.I.R. (Artist in Residence) sign that used to warn firefighters that artists were encamped in an otherwise industrial building — and/or was meant to honor Jane Eyre. The all-woman co-op SoHo-20, it should be noted, was founded the following year, which leads me to suspect that by 1973 SoHo as a term had caught on.

Ghosts of the legendary East 10th Street co-ops, such as the Area, Brata, Camino, Hansa, James, March, Phoenix, and Tanager galleries, were still about. These artist-run venues had seeded the Abstract Expressionist aftermath and, it could be argued, the art world as we know it. Here are some artists that were co-op members or invited guests, many showing for the first time:

Brata Gallery (1957 – mid-’60s): Ronald Bladen, Al Held, Nicholas Krushenick, Kusama, George Sugarman.

Camino Gallery (1956 – 1963): Elaine de Kooning, Alice Neel.

Hansa Gallery (1952 -1959): Allan Kaprow, George Segal, Robert Whitman.

Tanager Gallery (1952 – 1962): Alex Katz, Alfred Jensen, Philip Pearlstein, Myron Stout, Tom Wesselmann.

[Source: “Tenth Street Days; The Co-ops of the ’50s,” 1977, curated by Dore Ashton and Joellen Bard. Catalog essays by Ashton and Lawrence Alloway.]

In the ’50s, the East Village was just the Lower East Side, which included everything east of Broadway. That was before some bright person in a real estate office coined the new name to make some really tawdry brick apartment buildings on Second Avenue sound classy. It was hoped the area would be perceived as just the Eastern sector of The Village, famous far and wide as the capital of Bohemia, at least in the Big Apple, a.k.a. New York City or New Amsterdam.

Nevertheless, by 1972 co-op galleries, sometimes confused with vanity galleries, had a bad name — as if artists-run art stores could be any worse than strictly commercial venues. In vanity galleries, you pays your money and you gets your show, no sweeping the floor required. If the truth be known, many less-than-blue-chip galleries expect artists to pay for announcements, receptions, framing shipping and various other extras.

Vis a vis, co-ops where artists call all the shots, some artists actually have better taste than art dealers. However, unless sufficiently motivated by poverty, anger, some ideal or pet peeve, artists find gallery-sitting, collector-courting and critic-chasing boring. They would rather be home painting, or whatever. Chefs do not make good waiters.

A.I.R. had a mission: to expose women artists, whom everyone knew even then are not well-represented by commercial venues. This was true in 1972 and, although things have improved a smidgeon, it is pretty much the case today.

If you go, do not expect a Chelsea megaspace. That this anniversary sampling has to take place in two parts should give you a clue that you are stepping into the past. Or stepping into the future? This may be the size of galleries to come.

And as disillusionment with the commercial art world spreads, as profits sink and inflated reputations tank, artists – male and female — will once again create their own opportunities.

For me there is a certain déjà vu. I wrote about many of these artists years ago. So last week I revisited a larger-than-life hairy youth painted by Sylvia Sleigh (Annunciation, 1975); Patsy Norvell’s Glass Garden (1979-1980), a tool shed-size greenhouse with engraved glass panes; Judith Bernstein’s drawing of a gigantic screw (Bill Copley’s Bedroom, 1977) which looks like a giant penis; a decorated “cake” by Pat Lasch; and, of course, Agnes Denes’ classic Wheatfield, A Confrontation (1982), represented by a photo of the two-acre wheat field she planted in the landfill near the World Trade Center. But there are many artworks I haven’t seen before. New to me, for instance, was Barbara Siegel’s Sea Queen (2003), a beguiling and oddly moving fleet of paper boats. Still to come: Ana Mendieta and many others.

Barbara Siegel, Sea Queen, 2003

* * *

It’s Only Words

John Perreault, Worker Putting Finishing Touches on Guggenheim Facade, 2008

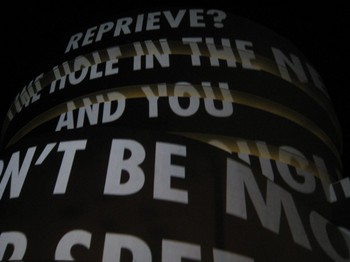

Jenny Holzer is at it again. To celebrate the restoration of the Guggenheim façade, she is projecting gigantic rolling texts on that very surface every Friday evening through Dec. 31. That curvaceous monument still evokes some pre-World War II fairground or a sound-stage building in Things to Come — so futuristic it is charming.

Holzer’s dusk-to-11 p.m. projections are futuristic too as they scroll, in all caps, up the pregnant belly of Wright’s masterpiece. They never come to rest and, depending where you stand, are distorted and sometimes partially concealed by the building-bulge. This adds a perhaps unintended mystery to the meaning of the texts, necessarily unattributed given the on-street, after-dark circumstances. One of my snapshots captures this meaningless string of words:

WITHIN AN INCH, A HAIRSBREATH FROM AN UNFORTNATE COINCIDENCE

Or how about this text:

I have a new insight into Holzer’s logomania. Slogans, aphorisms and other texts are not so much about whatever meanings one can derive, but about the act of selection and the acts of presentation. Do not confuse her “signs” with concrete poetry, or with the words and word fragments in Cubist paintings or those of Stuart Davis or even Robert Indiana.

More ambiguous, although completely legible on the Guggenheim website, is:

MORE PEOPLE AND NEW OFFENSES HAVE SPRUNG UP BESIDE THE OLD ONES – REAL, MAKE-BELIEVE, SHORT-LIVED…

Here’s the credits:

For the Guggenheim, 2008. Light projection. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Text (pictured): “Tortures,” from View with a Grain of Sand by Wisława Szymborska, translated by Stanisław Barańczak and Clare Cavanagh. © 1993 by Wisława Szymborska. English translation copyright © 1995 by Harcourt, Inc. Used/reprinted with permission of the author. © 2008 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Photo: Kristopher McKay

I guess somebody doesn’t want to be sued.

Although she has appropriated more words than any other conceptualist, Holzer is an abstractionist. The texts are often obtuse (or painfully banal). Someday I may get around to comparing her use of language to Lawrence Weiner’s or, further back, to the single-word poems of the young Aram Saroyan. You can see one of Holzer’s most effective “Truism” pieces, styled for the internet, here.

* * *

Hoofs Prints in the Dust

Can an artist be too original, too ambitious? Gillian Jagger, in my book, is truly an original, one of the most original artists I have ever come across. Her work is bigger than life in its homage to both beasts and geology, and her use of space. The problem is that she is difficult to classify: critics, curators and collectors want examples of categories, not precedent-breaking, back-breaking, space-claiming, raw sculptures.

Jagger makes casts of what appear to be heavily trafficked pastures, the mud around wilderness watering holes and the unsung trails of migrating herds. And these great chunks of plaster and latex are deployed within specific exhibition sites to exploit the drama and the grandeur of her themes.

You think at first you are looking at the crackled bed of a dried up lake or a marble quarry gone berserk, but then you see the hoof prints, at least in the present work, now at the Violet Ray Gallery, 727 Washington St. (at Bank) in Greenwich Village, to October 30. Many years ago, when visiting Africa, Jagger witnessed thundering herds in the wild. The image and the awe stuck with her, finally finding expression in these new works, under the title “In Between.”

When Jagger uses plaster, you don’t think of George Segal, you think of Nature. When she installs her gigantic flat (!) sculptures – whether as floor pieces, wall pieces, or something in between – she takes your breath away. Now, retired from teaching, she glories in her maturity. She is neither a Minimalist, anti-form artist, or Earth Artist. She is sui generis.

FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT WHEN EACH NEW ESSAY IS POSTED SEND YOUR E-MAIL ADDRESS TO : perreault@aol.com

PAST POSTINGS CAN BE READ BY CLICKING ON “ARCHIVE.”

THEN CLICK ON DATE OR SCROLL DOWN FOR

HEADLINES AND SUBJECTS.