Larry Rivers, The History of the Russian Revolution, 1965

How to Disappear

How do famous artists disappear? First, their artworks no longer figure prominently in selections from collections on display at major museums. They are placed to the side and then relegated to invisible storerooms and warehouses. After all, there is only so much room for art. And then – it is bound to happen, I’ve seen it happen – their names vanish from the art-history textbooks, too.

Maybe the work is simply no longer needed to legitimatize whatever comes next. Justification of new products by precedent is how much art of the past survives. Maybe just as you or I may become bored with some formerly cherished picture on the wall, a collective, cultural boredom can similarly set in.

But don’t classics and cultural icons transcend boredom? It depends on your mood.

Maybe the “ideas” are dead. Whatever “issues” the art represented, investigated, or created have been resolved or no longer seem all that interesting. Maybe everyone has suddenly awakened to how truly awful the now doomed art really was. Oh, sure.

And then we can always blame fickle fashion, a redundant phrase if there ever was one, but one that sometimes leads to the comeback trail. Suddenly what’s old is new again. The dog goes back to chew the same tired bone because no new bone has taken its particular place.

On the basis of a concise exhibition at Guild Hall in East Hampton, “Larry Rivers: Major Early Works” (to Oct. 19, 2008), the work of Rivers might be ready for another look. Of course, I was shocked that the show’s memorable Frank O’Hara Nude With Boots (1954) is not in some museum but still under the aegis of the Larry Rivers Foundation. I missed the 2002 Corcoran Gallery of Art Rivers retrospective in D.C., but although the Guild Hall sampling halts at 1965, there’s enough to give anyone pause for thought.

Perhaps Rivers (1923-2002) should not be so hastily relegated to the dustbin, by me or anyone else. Those startling paintings of his naked mother-in-law still hold up. Here, Double Portrait of Berdie (1955) is particularly unsettling. Painting your mother-in-law nude has to be one of the most bizarre choices in art history. Or maybe not. She was, Rivers claims, there. And available.

Is this painting anti-modernist? Or, in its bizarre embrace of realism, avant-garde? What did the artist feel? What are we expected to feel? Why is everything, in terms of the academic nude, slightly off? What is to be gained by trying to paint what you actually see?

And then, of course, it gets even better when Rivers starts up on Civil War veterans and cigar boxes, or so the story goes. And in the process invents Pop Art. Maybe.

This particular selection of his work ends with the spectacular, once controversial (a term that could be the Rivers epitaph) 32-foot painting/construction, The History of the Russian Revolution (1965).

So where on the Artopia braid shall we place the mercurial Rivers?

I’ve been reading Rivers’ autobiography called, amusingly enough, What Did I Do? — The Unauthorized Autobiography of Larry Rivers (1992). Not so long ago, it was an irresistible Strand or St. Mark’s Bookstore remainder. Larger than Moby Dick, this hulk was sulking unread in my library, not yet inserted into my strictly alphabetical array. Alphabetizing all my books on or by single artists is my latest and very labor-intensive artwork. The alphabet is one of my themes, as an artist.

Here I should note the shocking thing about my alphabetized monographs and artist writings: I make no old-fashioned, high-low distinctions. Painters are next to potters or architects. Sculptors are sandwiched between designers and folk artist.

I confess it was a miracle that I found the Rivers autobiography, because along with other orphan-victims of double-shelving, it was protected by a row of more recent acquisitions. Yet once I started reading it, I couldn’t stop. Rivers claims that his nemesis Clement Greenberg advised the late William Rubin, before he became chief curator and then director of painting and sculpture at MoMA, to sell the choice Rivers he owned.

According to a French artist friend who was present at the dinner party, “Clem told Bill he didn’t like my painting [The Daugherty Ace of Spades] and Bill said get rid of it.”

Rubin immediately put it up for auction. We, of course, know critic Greenberg was at that point in time backing Color Field.

Later I found Helen A. Harrison’s thoughtful 1984 book on Rivers at the Strand for $20. The Alliance of Independent Colleges of Art sticker was still affixed to the inside of its hard cover. Oh, the indignity of it. Another artist dumped by a consortium of art schools? Perhaps the AIC went out of business; perhaps they were getting rid of accidental duplicates.

In any case, I read that Uncle Clem had earlier praised Rivers: “the similarity [to Bonnard] is real and conscious, but it accounts really for little in the superb end effect of Rivers’ painting, which has a plentitude and a sensuousness all its own.”

In the unkindest cut of all, Rivers and his literary helpmate, playwright Arnold Weinstein, misspell Rubin’s name as “Reuben.” William Rubin will forever be memorialized as that famous grilled delicatessen sandwich: corned beef, Swiss cheese, and sauerkraut on rye.

So how, beyond the Rubin Reuben, will we ensure that Rivers will not be forgotten?

* * *

What Did I Do? is juicy. Having come up as a poet through the New York School of poets (Kenneth Koch was my teacher at the New School, where I won the Dylan Thomas Prize) I am fascinated to read the inside dope about my poetry elders, Frank O’Hara in particular. Not only one of the leading lights of the New York School, O’Hara was also a curator at the Museum of Modern Art. Rivers and O’Hara were more than friends. O’Hara was his goad, muse, critic. But do we really need to know that O’Hara got bitchy when drunk? Do we really need to know what Larry really thought about having sex with him? Rivers was not above biting the hand that fed him.

Speaking of hands, Rivers once slashed his wrists after having his romantic advances rejected by painter Jane Freilicher and was nursed back to health in Southampton by the honorable Fairfield Porter. For a crowd that had partied with de Kooning and Pollock, Freilicher and Porter are curious New York School favorites. Porter was kind and Freilicher has a reputation for being witty.

These tidbits would be valuable enough, but Rivers in confession mode tells us all the sordid details of his various marriages and flings, gay and otherwise. We learn more than we really want to know. Heroin and speed played a part, too. But what else can you expect from someone who started out as a jazz musician?

My point here is not that the autobiography is worthless because it is gossipy. Everyone loves gossip. Instead this confession may illustrate the self-centered bravado that caused Rivers to have so many enemies. Honesty is not necessarily truth. Normally I tend to think that the art and the artist illuminate each other. But here the persona and/or personality block the art.

So how can the Rivers art reputation be revived?

First Step:

Buy up all copies of the What Did I Do? and burn them. Well, copy out the parts that tell you about the poets and forget the rest. Copy River’s eulogy for Frank O’Hara (1926-1966) “…It is easy to deify in the presence of death. But Frank was an extraordinary man — and everyone here knows it. For me Frank’s death is the beginning of tragedy. My first experience with loss. I feel lonely.” Artopia actually attended O’Hara’s funeral in that little cemetery in The Springs (outside of East Hampton) where Pollock, Stuart Davis, Lee Krasner, Ad Reinhardt, and Harold Rosenberg also rest.

But Rivers, offending even moi, did go on and on in front of the busloads of mourners about O’Hara’s stitches and bruises. O’Hara was run over by a beach buggy on Fire Island.

Copy the section of What Did I Do? about taking classes with Hans Hofmann.

Copy whatever is truly illuminating.

Otherwise, if Rivers was really like he comes across in this so-called Unauthorized Autobiography, many were probably relieved when he fell from art-world grace. He was too much. And a subtext of the autobiography is that he got worse and even more self-indulgent and insecure as he aged.

On the other hand, so many really fine people liked him, he must have had a good side, and by this I mean something more than infectious enthusiasm, loads of charm, and a willingness to bed down with any ship in the night, of any age or gender. He certainly had a passion for art. Or was his true passion only for fame?

When he was writing the Autobiography he was already fading from view, so he may have overemphasized all the bad-boy stuff. Shocking confessions were then the rage. Alas, his life story is not the stuff of myth. No one is going to buy movie rights to The Larry Rivers Story. Hubris is now so pervasive that it is no longer a marketable theme. I mean, do we really have to know that as boy he was embarrassingly short and that his left breast was swelling up? Do we really have to know that as an adult, one of his habitual sex playmates was 15 years old? Although in an ideal world, art and artist are one, some biographies — certainly this autobiography — stand in the way of looking at the art. I can give you a list of artists I admire and I have written about but sometimes wish I had never met. My guess is that Rivers’ art will look better and better as his persona fades.

Second Step:

We must stop writing and thinking that Rivers provided the transition between Abstract Expressionism and Pop. Check the dates!

The Last Civil War Veteran [left] was 1961; Camel (meaning the cigarette package) was 1962; Dutch Masters was 1963. And George Washington Crossing the Delaware? Although not in the exhibition, it was 1953. Close, but no cigar. De Kooning had already done many of his Women, at least one of which had a lipstick mouth cut from a magazine ad. Although it is very odd that one of the originators of Abstract Expressionism should also be the instigator of its demise, this is indeed the case. It was de Kooning, not Rivers or Rauschenberg, who was the transition between AE and Pop. Furthermore, calling Rivers the transition between AE and Pop eventually turns out to mean he was nothing but the transition, doesn’t it?

Third Step:

Weed out the bad stuff.

Fourth Step:

Feature the good. We can’t trust the market to do that.

Fifth Step:

Look at the art, not at the man. Forget that he once won a lot of money on television’s popular “$64,000 Question.”

The Greatest Homosexual (1964), a riff on David’s Napoleon, is the best art joke ever.

And the History of the Russian Revolution (1965), although a bit cubistic, is complex and truly magnificent: real machine guns, Plexiglas, poet Mayakovsky (one of my favorites) committing suicide.

Once he left his precient realist period, Rivers appropriated hesitancy, false starts and erasures as a language, which, to be truthful, recall the mannerisms of certain kinds of academic drawing. On the positive side, those signs of process communicate vectors of perception and the honesty of doubt. The dubious Hofmann’s “push-and-pull” (it is amusing in the Autobiography to see Rivers, like everyone else, try to explain it) no doubt influenced him to exercise a kind of late Cubism. The same might be said of Robert Rauschenberg, notwithstanding the brilliant all-white paintings. But isn’t there also an alloverness in both Rivers and Rauschenberg? Once Rivers found what was to become his signature style, the multiplied, incomplete images hug the picture plane and are deployed like scattered leaves on a snow-covered sidewalk.

In the Manichean view of postwar art, it was a matter of the late Cubists holding on to quotidian imagery and multiple points of view against the Mystics, who were ultimately producing movie screens without the movies. And then there was full-blown Pop. And Minimalism. And Conceptual Art. Suddenly braids are more important than single lines or even pendulums, and we are in the Burgess Shale of contemporary art.

Rivers, I propose, should be celebrated, not as the iffy transition between AE and Pop, but as a talented realist and then the first post-World War II American artist to revive, renew and get away with making history paintings. Do we yet have any history painting as moving as Rivers’ History of the Russian Revolution? Is there anything that captures Vietnam or Iraq?

This is a tidy show, but what happened after 1965? We have 37 years gone missing. Leafing through Harrison’s book, I longed to see Golden Oldies ’50s (1978), the two 20-foot panels reunited. It’s an anthology of Rivers’ golden oldies, like a jumble of pop tunes assembled for quick resale. And then there’s The History of Matzoh (The Story of the Jewish People) from 1982. These are artworks you won’t find online. And, in any case, if the works I saw last week at Guild Hall are any example, no computer screen can truly convey the scumble, the scope and scale, and the tastiness of surface that was Rivers’ forte.

And then a show of all of his collaborations with poets?

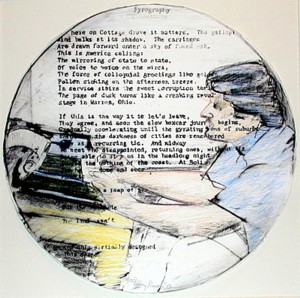

Larry Rivers: Pyrography: John Ashbery Working, 1984. Etching, etc.

FOR AN AUTOMATIC ARTOPIA ALERT EMAIL PERREAULT@AOL.COM