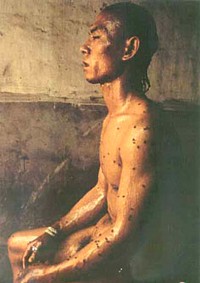

Zhang Huan,12 Square Meters, 1994.

Bubble Gum

Artopia pays no attention to the Chinese art bubble, nor to the bigger art bubble in general. Bubbles come and go. The Bigger Bubble is tied to the stock market. The stock market drops and the art market follows one year later. It has happened twice on my watch. Now it is real estate, everywhere but in New York City high-income zip codes, that is plummeting. Will art follow? Some say that the economy is now worldwide and that money piling up in the oil states will rescue art from the mortgage mess. Tell that to the citizens of Great Britain who are taking their money out of the banks.

Smaller bubbles are more easily arranged. Once upon a time, before Chelsea had replaced Soho as the Big Apple art district, Italian contemporary painting, pushed by art dealers and who knows what government forces, had a bubble too. Can anyone now spell out the last names of the artists then known as the Three Cs? What I call the German Trick had worked for the Germans, it almost worked for the Italians, and it did not work at all for the French.

The German Trick went something like this. In the ’70s, German artists were upset that native collectors were only buying American imports, as represented by Pop and then Minimalism and Conceptual Art. They put pressure on the dealers. I happened to be in Germany then, if only briefly.

The Germans then told the American dealers, we will not sell any of your U.S. artists unless you give exhibitions to our artists, who are, by the way, driving us crazy. Joseph Beuys was above the fray and already a legend, but his students weren’t.

I don’t really know why we have to look at and read about all of this bad Chinese art. Perhaps there is a dearth of saleable art product. As far as I know, there is no real market for American art in China. Do New York dealers and collectors smell profit? Are galleries now trying to hold their own against the auction houses? Artopia is not interested. This is what all of Artopia worldwide wants to know: Is there a Chinese Beuys?

Zhang, To Raise the Water Level in a Fishpond, 1997

Performance at Nanmofang fishpond, Beijing

Photograph by Robin Beck.

Beuys Will Be Beuys

On the strength of a relatively small show at the Asia Society (725 Park Ave., to Jan. 20), the artist who comes closest is Zhang Huan. Why this sampling is subtitled “Altered States” is beyond me. Has his form of Performance Art masochism altered his mind or has his art altered various states or countries?

Although Zhang may not be probing the depths of myth or consciousness, at least he is not silly. Beuys was responsible for a student strike in Düsseldorf and much else. Zhang, inspired by a trip to the U.S., seems to have been instrumental in starting up the Beijing “East Village” art district. Within China, his Performance Art was once scandalous.

I began by sitting through all six Performance Art documentaries offered. Was it because Zhang could not afford traditional art materials that he began using his own body? One text so asserts. I think he was just attuned to Artopia prerogatives. Even though he was at hand for the Tiananmen Square Massacre of 1989 and no doubt experienced the effects of the ignoble, misguided Cultural Revolution, he certainly could have heard about Performance Art and Body Art in the West. These art forms are difficult to censor because, after all, they are largely communicated by word-of-mouth, no matter how glorious or boring they may be in real life. Then post-Maoist neocapitalism opened many doors into and out of China. Zhang visited New York. And kept on visiting.

Zhang, My New York, 2002. Whitney Museum.

Performance Samples

1. 12 Square Meters, 1994. Naked, oiled or honeyed, the artist sits in a foul public toilet and is soon covered with crawling flies. He gets up and then submerges himself in a nearby pond.

2. To Add One Meter to an Anonymous Mountain, 1995. Naked men and a few naked women pile up face-down on top of one another to make the additional meter.

3. To Raise the Water Level in a Fish Pond, 1997. As far as I could see, all men and one boy step into a pond. There are no women. The guys are wearing the world’s ugliest underwear. Nevertheless, this is a more poetic extravaganza than To Add One Meter, particularly when the participants break the orchestrated, photogenic pose and move to leave the pond — which is somewhere in Beijing – and you see fish jumping.

4. Pilgrimage: Wind and Water in New York, 1998. Performed in the courtyard of P.S. 1, Zhang enters naked and does full-body prostrations, ending up lying face-down on a bed of ice. Dogs have been tied to the Tibetan-style bed.

5. My America, 1999. Presented at the Seattle Asian Art Museum, this is a full-scale group performance involving countless naked bodies, prostrations, hand-clackers, and what look like Tai Chi movements. The climax involves all the naked men and women climbing the surrounding scaffolding and throwing bread at Zhang. Then someone breaks an egg on his head.

6. My New York, 2002. The artist is carried under wraps into the Whitney Museum moat. When the white cloth is removed, Zhang is wearing a meat costume that makes him look like a superhero in a comic book or the current governor of California when he was a bodybuilder. Up on the Madison Avenue sidewalk, Zhang passes out white doves to bemused passersby.

“The body is my basic language,” says the wall text, quoting the artist.

Of the works shown, 12 Square Meters and My New York are the most evocative. I had already seen photographs of the fly performance, which might owe something to Yoko Ono’s classic film Fly, substituting a swarm for the single fly that explores a female nude in her great work. My New York was more effective on film than the widely reproduced photograph of the artist in porterhouse drag. I will never forget the brief shot of two young N.Y. cops on Madison Avenue. One is standing with his mouth open, obviously in response to Zhang’s meat regalia. And I suppose I liked the fish pond piece too, though the kid on one man’s shoulders verges on sentimental.

Zhang is much taken with Tibetan Buddhism, so it is not surprising that he incorporates Tibetan chanting, drums, and the suggestion of rituals, all of which I question. Buddhism is a minority religion in China and, as we know in art circles, China has been repressing Tibet for far too many years. Nevertheless, I don’t think most Westerners would like a Performance that featured nuns praying (unless they were bald or naked) or the Mass (unless it was a Black Mass). Or Baptism. I suspect, however, Zhang is trying to make a political point, rather than convert his audiences to Tibetan Buddhism.

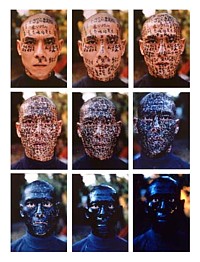

Zhang, Family Tree, 2000. C-prints, ed. 25.

And Now…

Passing through the glass doors into the formal exhibition space, we see attractive, large-scale photographs of the performances already endured; and also photographs of ½ (1998), in which Zhang is wearing bloody pork ribs and his face and body are painted with calligraphy, forcing me to wonder if he had ever seen Iran-born Shirin Neshat’s use of Arabic in her 1994 photo series, called “Guardians of Revolution.” This is not to question Zhang’s originality (or the place of originality in art now), but to show how his work is embedded in contemporary modes of expression.

I also liked Family Tree, 2000. The artist hired three calligraphers to gradually cover his face with the traditional folk story of a foolish old man and his sons who moved two mountains by digging a little bit each day. In the last of nine photographs, Zhang’s face is completely blackened by ink. What does this mean? That patience is ridiculous? That useless effort is foolish? That useless effort is art? Or that you can hide behind language?

Having worked our way through Zhang’s Body Art Performances, we can safely proclaim, long live Performance Art.

Like watercolors or artist films, Performance Art is part of the international art vocabulary, perhaps best attempted earlier rather than later in a career. Sensationalism is a good way to get attention. Here a good example is Chris Burden having himself shot in the arm or getting nailed to the hood of a Volkswagen. Artists have validated various kinds of Performance Art — as occasional forays into dance (Robert Rauschenberg, Robert Morris); as life-long and exclusive pursuits (Allan Kaprow, Marina Abramovic); and even as integral to complex careers (Yves Klein, Joseph Beuys). Performance-generated photo art is yet another category (Cindy Sherman, Ana Mendieta). When there is a cast of performers (playing roles or not), we impinge on theater.

In any case, if there is a physical residue, these leftovers accrue the meanings of their genesis as props and begin to appear as sculpture. A gun used to shoot Lincoln — if one were available — would have a different meaning than one, outwardly identical, that had been used to kill a deer.

Zhang, Fresh Open Buddha Hand, 2007.

From Actions to Objects

Performance Art, most relevant to Zhang is the reiteration of the well-worn career pattern of moving from Performances to sculpture, the latter being infinitely more saleable. None of Zhang’s Performances equal the spectacle of a gold-leafed Beuys explaining art to a dead hare. Or Carolee Schneemann’s scroll piece. Or Vito Acconci’s masturbatory Seed Bed. Or Yoko Ono’s Cut. Nevertheless, unlike the Asia Society educational material that fails to provide an art context for Zhang’s Performances, Artopia is providing that service.

When a much younger John Perreault was hanging out with Acconci and Scott Burton and making Performances himself, he and his fellow conspirators often talked of how Claes Oldenburg, in the previous generation, had moved from Happenings to sculpture. Was this honorable, viable, something to imitate? Perreault (foolishly it turns out) thought it was a kind of betrayal of anti-object art. Forthwith, Burton, like Oldenburg before him, turned his Performance props into art; chairs were offered as sculpture. Acconci, who was a poet, became an installation artist (and now, some say, an architect). Roles and identities morph.

Eight years ago, poet, painter, critic, curator, and art administrator Perreault — whose best Performance is the ongoing “Anytime I am recognized in the street by someone I don’t know is a Street Work” — had an out-of-body vision or waking dream of himself whirling on the corner of Flatbush and Fulton in Brooklyn, near where he was then employed. In case you don’t know it, this is a major crossroad, one of the busiest intersections on Earth.

And while Perreault was whirling at breakneck speed, across the street from the portioning out of Junior’s cheesecake in its brief deep-fried version, he turned into various iconic animals: a bear, a wolf, a rabbit, etc. His favorite Yoruba god then was Elleggua – Lord of the Crossroads, messenger of the gods, trickster, diviner — and he had always been fond of Mercury. His theory now is that we all live so long (if we are lucky) that we reincarnate several times during one lifetime. We live several lives and are several different people. So why shouldn’t a painter like Julian Schnabel become a film director? Or a Performance artist become a sculptor?

Zhang is following a certain pattern. Admitting that in terms of Performances he can think of “no better ideas,” he is now making everyone happy with his 100-man studio/factory in Beijing. There, he and his staff are turning out gigantic copper sculptures, temple-ash encrusted self-portrait busts, and – as seen in the Asia Society educational film — giant woodcuts with line drawings and feathers superimposed. We don’t see these woodcuts in the exhibition, but we do see two of his truly impressive copper-sheet enlargements of Buddha-statue parts. These are modeled on collectible remnants of Madame Mao’s Cultural Revolution. Statues of the Buddha were ordered melted down so the metal could be used for more utilitarian purposes. Like what? French horns for her campy “operas,” such as The Red Women’s Detachment?

Recently, I saw Yang Ben Xi – The Eight Model Works (2006), a documentary about Madame Mao’s venture into show business. Since she and the Gang of Four controlled movie distribution in China as well as everything else, this former actress, who was the Chairman’s widow, was able to control propaganda and in the process almost destroy for all time traditional Chinese opera, which is older than opera in the West. As reported in Yang Ben Xi, these Maoist operas – with their infectious songs and ’50s Hollywood dance sequences — are now the rage in China, having become, in the face of rapid Westernization, objects of nostalgia.

And I saw Jim Finn’s amazing (and droll) Interkosmos (2006) which, filmed in Chicago and Ithaca, New York, purports to document a failed East German attempt at colonizing Titan and Ganymede, both moons of Jupiter. (The women’s field-hockey dance sequence is alone worth the trip.

These films suggest that Zhang’s group performances might have something to do with the communism of his youth. Zhang’s art – whether the solo Performances, the group pieces, or the sculptures – can be seen as anti-Maoist statements. Suffering, although overtly the form of the early solo performances, is the content of the work in general.

The educational film on Zhang, on the other hand, is a snore. If the Asia Society wants to get on the contemporary-art bandwagon – which is not a bad idea – it has to come up with a larger exhibition space and jettison the cliché educational apparatus that museums use for the art of the past. We don’t really need sappy interviews with one or another of Zhang’s studio workers sucking up to the boss. It would be enough to say in a wall text that Zhang now has more studio assistants that Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst and Matthew Barney combined. Furthermore, it is not much of a novelty to reveal that an artist does most of his work by pointing his finger, the way super-rich gardeners do their gardening on their Long Island estates. Current studio practice makes Andy Warhol’s Factory seem hands-on.

But I did take away from the little movie about Zhang an important phrase. In the back seat of a car in Manhattan, the artist says he is often asked where his New York studio is. He answers, “My studio is in my brain.”

For an e-mail Automatic Artopia Alert concerning new Artopia postings, contact perreault@aol.com.

John Perreault's art diary