An Embarrassment of Riches

Another thing about Semina is it’s un-American. In the fifties, when the magazine first began, it was against what in those days we called ‘The American Way.’ Semina was a long way from the American Way. The American Way was the Korean War, the grey flannel suits, the military preparedness to wage war behind the Iron Curtain or the Bamboo Curtain.

Michael McClure, “On Semina,”

Support the Revolution: Wallace Berman, ICA/Amsterdam, 1992,

How do you fill in the blanks when there are no places or sentences with blanks because the sentences have been filled? And language too? And art history?

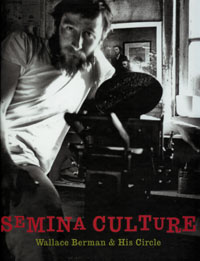

Contemplating “Semina Culture: Wallace Berman & His Circle” (Grey Art Gallery, NYU to March 27), I wonder what youth now can make of such stuff. I suppose it could be an inspiration; in fact, I propose it should indeed be an inspiration. You’ll see why as I try my best and most sympathetically to describe this now alien phenomenon: art made without an immediate profit in mind; art made the way birds make nests or sing or cry out in warning or pain; art made for other artists, wherever and whomever they are, even if unrecognized by the art machine.

Isn’t that embarrassing?

Wallace Berman (1926-76) is one of art’s mystery figures. He read a lot, didn’t talk much and apparently had a lot of friends. He was the hipster, the proto-Beatnik.

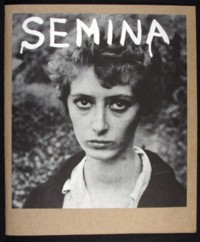

“Semina Culture,” a dense compendium of strange artworks and what could be seen as memorabilia, originated at the Santa Monica Museum of Art. I love Berman’s anomalous sculpture (Homage to Hesse, 1949) made when he was employed by a furniture-making shop. I also cannot resist Jay DeFeo’s (1929-1989) paint-splattered stool, used while she was working on The Rose (1959-66). A little mirror beneath the stool lets you read the inscription: “For Bruce/ love, Jay/ ‘we are not what we seem.’ ” But the core of this multimedia exposé are the issues of Berman’s magazine Semina (1955-64). All nine, no two alike, were hand-printed, not bound, came out irregularly, and could not be bought.

Berman sent Semina to friends. The ravages of time have made it all look good, the images and the words having accrued a forlorn patina. But I suspect, given Berman’s propensity for fake facsimiles — see his “parchment” works that some think were influenced by the look of the newly discovered Dead Sea Scrolls — Semina looked old when it was new. The cases showing the pages of this legendary publication are truly shocking. The mixture of poetry and art and of past and present is no longer possible. Names that pop up are Michael McClure, Jean Cocteau, Herman Hesse, Philip Lamantia, and the mysterious Cameron.

Cameron (1922-95), a follower of black-magician, one-time heroin addict Aleister Crowley, starred in Kenneth Anger’s underground film classic Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome. If you don’t know who she was, which is likely, you will not know that she was married to a handsome rocket scientist — occultist Jack Parsons, co-founder of the Jet Propulson Laboratory. He died in a mysterious explosion in his garage. If you have the patience to find out what Parsons might have had to do with the Philadelphia Experiment, the so-called Montauk Project and what this time/space shift, real or not, actually was, then you will be driven totally over the edge.

Currently there is a first-ever exhibition of Cameron’s art at the Nicole Klagsbrun gallery.

By the way, also in the Berman Circle of 40 collaborators were Allen Ginsberg, Robert Duncan and Jess, Bruce Conner, Russ Tamblyn, Diane DiPrima, David Meltzer, Zack Walsh, George Herms, DeFeo, Dennis Hopper, Bobby Driscoll, Dean Stockwell, Billy Gray (of Father Knows Best), and Zack Walsh, whose scroll poem needs to be unrolled. In my short list, I intentionally mix poets, artists, and actors. After all, except for a few years in San Francisco, Berman was definitely and definitively the L.A. art magus. Actor and director (Easy Rider) Hopper now has credence as a photographer, and both Driscoll and Stockwell produced some fine photo-collage artworks.

Berman and his wife moved to San Francisco when his one-and-only exhibition in a commercial space (the Ferus Gallery) in 1957 was raided by the L.A. police in search of pornography. They picked up a raunchy, peyote-induced drawing by Moonchild — red-haired, ex-WAC Marjorie Elizabeth Cameron — that was on the floor as part of a Berman installation. Berman was brought to trial. His toying with an art career had soured, so he was off to pre-Summer of Love San Francisco, to spread the word.

But in those days — the ’50s and early ’60s — if you were a Bohemian or a Beatnik, the differences between L.A. and San Francisco were not so important. All places in California were under the gun, under the wire, under the radar.

When I was in San Francisco in 1961, people sneered at L.A., but perhaps I had come across the wrong Beatniks. What did they think of Berman, who used Hebrew letters in his art? Why was North Beach so anti-Hollywood? So anti-automobiles and freeways?

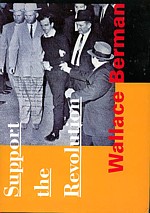

Some of my Berman information comes from Support the Revolution: Wallace Berman, ICA/Amsterdam 1992. I had stashed it away for future reference. Possibly because of Berman’s interest in the Kabbalah? In any case, there’s a discount sticker on it. (I paid $5.98.) So here’s another reason why I will never sell my library. The Berman book is full of archival material. Pictures of his early jazz illustrations, the posters he made for others. Lots of Berman mail art that his friends saved.

Had I read the texts? The book looks as good as new. Although I rarely write in books — good book-training has taken its toll — I find that on page 41, on the margin of an essay by L.A. Times art critic Christopher Knight called “Instant Artifacts,” I penciled in: “touch? dreams? deceptions? rejection? travel? prayer?” This is in regard to Knight’s hypothesis concerning Berman’s twelve parchment-on-canvas “drawings.” Twelve seems to represent the 12 “simple” letters of the Hebrew alphabet, 12 months of the year, and “the 12 avenues of human experience: sight, smell, hearing, speech, taste, sexuality, work, movement, anger, humor, imagination and sleep.”

So Berman gave away his magazine. As an artist, he also had a scandalous tendency to embrace one-day exhibitions, sometimes in community centers (Topanga Community House, 1967) or saloons (the Mermaid Tavern, 1973). But as a gallerist himself, during his S.F. stint, sojourn, exile, he perpetuated brief, one-day exhibitions for others on his houseboat in Marin County, hours 3 -5. Almost everything else was Mail Art. Or drugs.

Berman died in a car crash in Topango Canyon. But, as befitted the time, some of his cohorts, according to wall texts, were done in by bad chemicals.

Ben Talbert (1933-74) died from an overdose.

Arthur Richer (1928-1965), addicted to barbiturates, alcohol, and heroin, died of an overdose.

“After 15 years consumed by drug addiction,” actor/artist Bobby Driscoll (b. 1937), who starred as the little boy in The Window, died in 1968, his body “discovered in an abandoned Greenwich Village tenement.”

But there were other ways of dying:

Lew Welch (1926-71) suffering from depression “disappeared into the woods of Northern California and his body was never found.”

John Reed (1933-01) became addicted to methamphetamines and ended up living on the grounds of the Pasadena Public Library.

Loree Foxx (1929-72) was arrested as an indigent while traveling through Arizona. When she had an asthma attack, she “was given medicine that killed her.”

Billy Jahrmarkt (1936-73) was fascinated with guns and, living in Afghanistan, “accidentally shot himself and bled to death.”

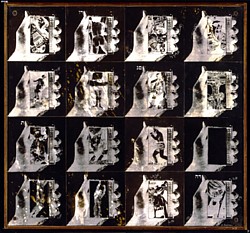

Wallace Berman: Silence Series #7, courtesy Corcoran Gallery of Art Museum, purchase William A. Clark Fund. www.corcoran.org. For illustrational, educational purposes only.

Wallace Berman: Silence Series #7, courtesy Corcoran Gallery of Art Museum, purchase William A. Clark Fund. www.corcoran.org. For illustrational, educational purposes only.

These were artists with no strong signature. Berman himself, it turns out, did have a signature artwork: the Verifax collage. Verifax was a messy, pre-Xerox duplicating system. In New York, I once had a temp job Verifaxing documents for a management consultant firm. I can still smell the chemicals. Berman used the image of a hand holding up a transistor radio as his template, affixing other images where the speaker would be: pop, personal, pulchritudinous, political, particular. The images were lined up in a grid, or sometimes like a hand or a fan of cards.

He also painted Hebrew letters on stones. In regard to his use of the Hebrew alphabet, most commentators find no sense or meaning in the letters. They are there because, as everyone knows, G-d created the universe using the Hebrew alphabet — and, some say, also used the spaces between the letters and within the letters.

Berman himself did not limit himself. He even concocted a film. The eight-minute Aleph (1956-66) is on view at the Grey. It’s a kind of painted-over collage of Verifax subject matter with the feel of a bebop riff, revealing the artist’s longtime appreciation of jazz. Berman painted directly on the 8mm film; the globs of once-red paint break into flecks and fragments, recalling his earlier “parchment” pieces. It is one of the great, great underground films. And not nearly as appreciated as it should be.

Berman’s motto was: Art is Love is God.

Isn’t that embarrassing?

Berman was lucky. He had curator Walter Hopps (1932-2005) to promote him. The self-taught Hopps was co-founder of the Ferus Gallery and then went on to a brilliant museum career, first as curator and then director of the Pasadena Museum of Art, where he inaugurated the first Duchamp museum retrospective and the first museum survey of Pop Art in 1962. Then on to the Menil Collection in Houston. Hopps considered Berman seminal, at least for California art.

L.A. needed an art history not connected to universities and art schools, which were already taking over. L.A. needed an underground art to match up with L.A. Noir. California needed an avant-garde.

REMINDER: IF YOU’D LIKE AN EMAIL ARTOPIA ALERT WHEN I POST NEW ENTRIES CONTACT ME AT perreault@aol.com

John Perreault's art diary