Daniel Rothbart, Meditation/Mediation (Camels, Wadi Shlomo, Israel)

Camels Munching and the Mississippi Passing By

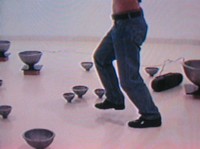

In a Roman backyard near a big tree, a man singing softly to himself walks around a circle of twelve cast-aluminum bowls of various sizes; he stops, kneels down and sings into the largest bowl; then he gets up and taps it with an aluminum gong-striker that looks like a giant sex-toy. The man is the artist Lucio Pozzi.

An anonymous “Algerian Entertainer” in an Israeli hotel is seen teaching dance movements to a group of ladies; the twelve bowls are on a table in the foreground.

Camels, munching on straw, poke at the bowls, sounding them.

Michael Kennedy, an Elvis imitator, does his turn in a Las Vegas parking lot, then, using the sex-toy, strikes the aluminum bowl at his feet.

Beni Corri, an Israeli performance artist, empties his pockets and, naming each item, places it on the floor in front of him: “My telephone [a cell-phone], my keys.” Then, removing each from his wallet: “My notes, my credit card, my visit cards, my wife [a photo], my son [a photo], my daughter [a photo], my prayer, my driver’s license, my i.d., my money, and [finally] my wallet.”

The aluminum bowls have been there all along; he uses one as a kind of bongo drum, beating a fast rhythm in front of a boom-box tape-recorder; plays back the tape and, lifting his shirt and jacketup under his armpits to expose his torso, does a cheerful dance around the room

He then begins to reassemble the things from his wallet, this time using an ambiguous “our.” Is he referring to himself in the plural? It can’t be the “our” of coupledom, because not only does he say “our son” he says “our wife.” And once he has put “our notes” into “our wallet” he bows with a solemn “Thank you very much.”

Artist Giordano Pozzi, son of Lucio, in the Roman backyard at the Fondazione Baruchello, places three paper sculptures into three of the aluminum bowls, sets fire to them, tends the fires, then scoops up the smoldering ashes with his bare hands and places them in a smaller bowl.

Critic Enrico Pedrini, outdoors against a graffiti mural, announces “Meditation on dissipation” and then throws his books to the ground near the bowls, where the wind turns their pages.

Critic and curator Achille Bonito Oliva, sitting before one of the metal bowls in his study, proclaims: “The critic vomits words of analysis into the synthetic form of the vessel…”

Rothbart, Meditation/Meidation (Beni Corri, Performance Artist)

We see these events in the form of a projection piece called Meditation/Mediation, part of Daniel Rothbart’s solo exhibition at the Andrea Meislin Gallery (526 W. 26th St., to Nov. 27). Are the recorded events Street Works, Performances, Found Art, Dada Events? Some could be seen as Street Works, some as Performances, some as rituals. Making a video, in some cases, facilitated other artists’ artworks (Bernardo Scolnik’s nude, new age celebration; Wayne Bartlett‘s accordion, pop-up suitcase enclosure emitting altered bowl-sounds); inspired rituals such as Francine Hunter McGivern bowing, using a bowl as a hat; or the simply documented bowls in front of a street musician in Israel and a silvered mime in New Orleans.

And I mustn’t forget the bowls on a Mississippi embankment: silent, as a ferry slides by with the sound of its very own clangs.

Rothbart, Medtation/Mediation (Mississippi River)

I Like It, But What Is It?

Street Works are ephemeral artworks or actions placed in or taking place in the streetscape, usually referencing and inspired by that particular social and physical environment, not necessarily for an informed audience.

Performances are nonmatrixed artists’ theater — more structured than most Happenings and more complicated than Fluxus Events — presented in theaters, auditoriums, gymnasiums or other nonpublic sites always for an informed audience.

As part of what I now like to call the New York Street Works and Performance Group (Vito Acconci, Scott Burton, Eduardo Costa, Bernadette Mayer, Marjorie Strider, Hannah Weiner and myself), I coined the term Street Works in 1969, playing off of the then burgeoning Earthworks. In terms of indoor presentations, Burton preferred Theater Works, but Strider coined the term Performances, which seemed to stick — later, but to all the wrong kinds of artist presentations. Performance Art in the ’70s became more like stand-up comedy monologues than sculpture or dance. Analysis gave way to entertainment, usually not very good entertainment at that.

Where have Street Works and Performances been the last 30 years? Could it be they were forced underground by commercialism? Or that they no longer provided an inside track to an art, movie, or pop-music career? The history was buried under the rush to comodification and show-business cash.

Yet the idea of artist-initiated, non-object art forms and formats lives on and will blossom unexpectedly now and again. Everyone thought that Futurist and Dada theater was locked into art history, but then Happenings came along in the ’50s in the U.S., and Fluxus world-wide.

In a sense, Street Works and Performances have become just one of many genres available to the contemporary artist as he or she becomes the fashionable author of the ubiquitous one-person group-show. So unless there’s some retention of the spirit of opposition or some new territory at stake, performance-based, non-object art forms are just there as loss leaders. They usually can’t be sold, but they give the related objects the aura of the avant-garde.

Rothbart: Meditation/Medation (Enrico Pedrini Throwing His BooksDown)

Streets, Dens and Yards

This is not the case with the art in Rothbart’s exhibition. The branchlike, cast-aluminum sculptures refer to the tree image central to the Kabbalah. They thus provide a grounding for his12 bowls — also of cast aluminum — that are the focus of his Street Works, Events, and Performances. Rothbart’s Semiotic Street Situations are documented by handsome color photographs. The more recently initiated Meditation/Mediation is performance-oriented.

There’s more to the Kabbalah than Madonna. But here I can no more than outline the link between the Kabbalah and Rothbart’s very Japanese-looking bowls, perhaps indicating a tentative match or mash between Jewish mysticism and Buddhism. The bowls are shaped like the most widely known tea-bowl form: a demisphere poised on and uplifted by a much narrower stem or foot. A lotus, in effect. Since the artist places these in various street situations and then photographs them, at least one part of their meaning is that of Buddhist monk begging-bowls. In conversation, the artist sometimes even refers to them as begging-bowls.

The bowls, however, are also the vessels in Luriac (and thence Hasidic) Kabbalah. The energy or the light or the meaning poured from the Unknowable-Unnameable-Unlimitable down, down the Kabbalah tree, from vessel to vessel. like champagne poured on the top of one of those wedding-glass pyramids. At this wedding, however, the vessels at the bottom are not strong enough, so they burst, leaving shards containing sparks of the Light. These somehow must be liberated and returned.

This was the innovation of Isaac Luria, The Lion of Safed (1534-1572) who was only at that mystical city for two years, taught endlessly, wrote a few prayers and then expired from the plague, having been what certain Sufis might have called The Pillar of his age. To see his grave click here.

Luria’s taught that the vessels must be repaired, the sparks returned, and then the Messiah will come — or at least there will be Redemption. To risk another symbol, that’s it in a nutshell. The world is but husks.

Lightweight enough to be carried in a big canvas sack, Rothbart’s bowls have been placed by the artist on the banks of the Seine, in front of a traveling circus in Italy, in Israel.

The Performances came next. The closest we can get to them is the Meditation/Mediation, which we will therefore take as a work in itself. It documents and provides the reason for more than two dozen actions (to use another term) or interventions (favored by Rothbart): in the backyard of the Foundazione Baruchello in Rome, in Israel (in Eilat and Herzliyat), in Nice, in New Orleans and Las Vegas.

Meditation/Mediation is refreshingly unslick. In those segments, shot at the Foundazione Baruchello with a very homey audience of friends and acquaintances sitting about on the lawn, we even see the artist once, standing dreamily by his camera, caught off-handedly by the Foundation videographer.

Aren’t we a little tired of those clear, cold, projected digital images we see everywhere now in galleries? What do they show? What are they other than advertisements for themselves?

Meditation/Mediation is over an hour, so most gallery-goers will not have the patience to view the whole thing. I think it should be shown in a movie theater, but I did my best. And then I looked at Rothbart’s DVD on my own monitor at home, where the images and sounds are clearer and oddly enough afford a distance from the thought that Rothbart might be nothing more than a facilitator. As if that were not enough. I concluded that his use of other artists (and critics) is Warholian, and as with Warhol, the results are all his.

Rothbart: Meditation/Mediation (Wayne Bartlett)

Imagine Peace

The segments, in no matter what order you look at them, add up to something very complicated. The Yoko Ono spirit is present throughout and not just because her motto Imagine Peace, per her instructions, was placed on the backyard tree in Rome. The separately filmed events end up as a braid of genres, and the bowls take on an eerie presence. Surely time, place, and friendships are equally themes. Rothbart’s blend of amateur shindigs, street performers, artists shticks and even landscapes (and camels) is charming and elevating. I suspect a few fallen sparks were set free. Symbols are not just a convenient way of expressing the normally inexpressible. After all, the bowls do not allow just anything to happen; symbols, correctly understood, also create realities.