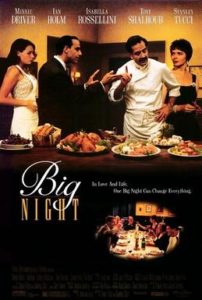

Big Night, released in 1996 and directed by Stanley Tucci and Campbell Scott, is a fabulous film, but also an outstanding allegory for arts management. Tucci, also the co-author, described it as “about the struggle between art and commerce and the risk of staying true to yourself.” Two Italian immigrant brothers—Primo, a creative genius of a chef, and Secundo (Tucci), his more practical younger brother—struggle to keep their authentic Italian restaurant in business in 1950s New Jersey.

Primo is an uncompromising artist in the kitchen, frustrated with unsophisticated patrons (calling one woman a “Philistine” for wanting a side of spaghetti with her risotto). Secundo has the greatest respect for his older brother’s gift, but is stuck with sparse and cranky customers, overdue bank loans, and poor prospects for a sustainable business.

Meanwhile, up the street is Pascal’s, a restaurant catering to the common throng—heaps of bad Italian food and cheap chianti—which is always packed and raking in the cash.

The brothers’ last chance is one big meal for Louis Prima and his band—a publicity stunt to get attention and build an audience. Building up to the Big Night, Secundo is torn between the excellence and artistry of his brother, and the commercial pandering of Pascal.

In one particularly wrenching scene for anyone in the arts, Primo quietly sighs his disappointment with the way their world is working:

Primo: People should come just for the food.

Secundo: I know, but they don’t.