There’s been lots of chatter in the economicsphere about Thomas Piketty’s new megabook on Capital in the 21st Century (read a quick summary of the looooonnnnngggg book here). It offers a ponderous and rigorous overview of where economic inequality comes from, and why the marketplace alone won’t fix it. In the process, more to our purposes, it offers an extraordinarily useful perspective on wealth.

Nonprofit cultural organizations are often concerned, after all, with wealth. We need wealth to build things and buy things. And we need people/institutions that hold wealth to convey some of their earnings to our operating budget.

But, what is wealth? Is it land and property? Is it piles of cash? Is it investments or patents or intellectual goods? Is it the people who control these things?

As this useful article summarizes it, Piketty’s definition is that wealth is a socially constructed category, formed by and intertwined with laws, policies, and other social factors. We tend to think of wealth as a collection of ‘things’ — buildings, land, bonds, stocks, etc. And we tend to think of those things as separate and non-political. But those things only have value to the extent they can generate future streams of income. And those future streams are defined (almost entirely) by law, policy, and social context.

As the article states it:

”Market values, and therefore wealth, do not track objective valuations of things in the abstract; rather, they track the valuation of legally constructed rights and powers with regards to things.”

So, wealth isn’t a network of things owned by people that are protected by the law. It is a network of control and power relationships created by the law.

But before I grow a bushy beard and rail about the cruel fate of the proletariat (which I might do), it’s worth connecting all this back to cultural enterprise. And I see it connecting in two essential ways:

- Since nonprofit cultural managers engage ‘wealth’ in many ways — philanthropy, local politics, governance, grants — it’s rather useful to understand with some specificity what, exactly, we’re engaging.

- Since we use ‘capital’ or ‘wealth’ to accomplish our work (endowments, buildings, equipment, intellectual property), it’s also worth acknowledging that the nonprofit version of ‘wealth,’ by definition, looks and behaves rather differently than its commercial counterpart. It generates a flow of future revenue that is (on purpose) less than it costs to build or buy. That’s not a small difference. So our thinking and strategy must be different, as well.

I will be reading Piketty’s tome this summer, because that’s what scholars do for fun (we are not very bright in a range of ways). Whether the book creates future streams of insight worth the effort of consuming it, I will let you know. I know you can’t wait to find out.

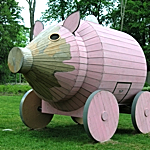

Sculpture in image: “Trojan Piggybank,” wood and steel, Actual Size Artworks (Gail Simpson and Aristotle Georgiades), 2004

“It generates a flow of future revenue that is (on purpose) less than it costs to build or buy.”

I’m gleefully exposing my ignorance here, Andrew, but I didn’t follow that sentence. The antecedent to the first “it” is clearly “wealth,” but to what does the second refer? I’m confident that there lies profound insight, but… “Build or buy” WHAT? Please elucidate.

Fair point, Jim. Sorry to be opaque. Both pronouns refer to the ‘wealth’ in whatever form we construct it for our work. So, for example, we intentionally build arts buildings knowing they will never generate future revenue streams to cover their original cost (that is, through earned income). We do this, of course, by getting other people to pay for their construction.

Hope that helps. As Daffy Duck would say, I’ve created ‘pronoun trouble’:

http://youtu.be/LyPFQKpRnd0

Thanks, Andrew. Right you are: I knew the insight was worth pursuing.

I’m sorry, the difference that I see between an NPO and and a commercial business is that the NPO asks for money and the business earns it. That’s not to say that NPO’s don’t earn the money they receive, but it’s not like they only fund raise until they get “enough’ and then stop fund raising.

A business has to put some of their money aside for future projects where the NPO spends everything they recieve and when they have a new project they just find someone to fund it. Businesses pay taxes, where NPO’s create tax breaks for their donors.

But both entities have “…buildings, equipment, intellectual property…” it’s just that businesses buy them with profits (or loans, which have to be paid back) and NPO’s have them “endowed”.

Greg, your point is certainly true for NPOs that receive the significant portion of their total revenue from contributed sources. But arts nonprofits tend to receive around half of their income from earned income (varies by discipline and organization size). So they actually live in a middle-world where capital is supported BOTH by earned income activities (retained earnings, debt, etc.) and by contributed sources (donors, grants, etc.). This puts them in a complex territory where decisions around ‘wealth’ or ‘capital’ have multiple means of evaluation and application…sometimes conflicting.

The smarter nonprofits do NOT spend everything they receive, they retain earnings too. How much they retain is another delicate balance of mission-delivery and organizational health.