Long-range planning is a lot like dieting and exercising: We all have a sense that we should be doing it more, but figure we’ll get to it after the current doughnut on our desk. We hear the nagging voice of reason whispering: ‘People don’t plan to fail, they just fail to plan.’ We glare at the foundation grant requirements asking for a copy of our current 25-year master plan, and wonder if a photocopy of our ‘month-at-a-glance’ scheduler will do.

Part of the problem with long-range planning is that it just doesn’t make conceptual sense. When your work is primarily driven by forces beyond your control — economy, technology, social systems, demographics — and those forces are under radical flux, how can you manage a plan for even one year let alone five?

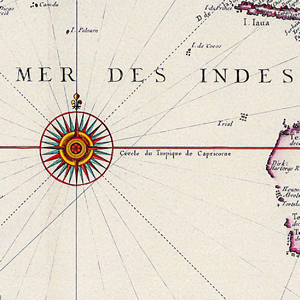

In his 1992 book Managing the Unknowable, Ralph Stacey uses a ship navigation metaphor to describe the problem (a well-worn metaphor, I know, but here it’s used to good effect):

The trouble with standard maps and traditional navigation principles is that they can be used only to identify routes that others have traveled before: they can make sense only for managing the knowable. Only under familiar conditions can the captain identify the ship’s future destination, and only under such conditions does it make sense for the members of the team to follow the leader slavishly. An old map is useless when the terrain is new. Old beliefs cannot help in the task managers face today: managing the unknowable.

Stacey’s solution is to downplay planning altogether in favor of more dynamic, self-organizing entities that plan as they go. Others have suggested that planning still has a useful place at the table, but that it must be radically different than the traditional models allow.

One such effort over the past 20 years has been scenario planning, an exercise that encourages deep discussions of various alternative futures, knowing that none of them is exactly true. Global Business Network has been one of the key refiners and definers of the scenario method, and released a new guide for nonprofits this month entitled What If? The Art of Scenario Thinking for Nonprofits (available as a free download). According to the authors:

Scenarios are stories about how the future might unfold for our organizations, our issues, our nations, and even our world. Importantly, scenarios are not predictions. Rather, they are provocative and plausible stories about diverse ways in which relevant issues outside our organizations might evolve, such as the future political environment, social attitudes, regulation, and the strength of the economy. Because scenarios are hypotheses, not predictions, they are created and used in sets of multiple stories, usually three or four, that capture a range of future possibilities, good and bad, expected and surprising. And, finally, scenarios are designed to stretch our thinking about the opportunities and threats that the future might hold, and to weigh those opportunities and threats carefully when making both short-term and long-term strategic decisions.

Like any group facilitation process or thinking tool, scenario planning has its proper place and time (if you can’t make this month’s payroll or your facility is on fire, for example, it may not be the best time for a scenario retreat). But for those searching for a different way to talk among their staff, their board, their affiliated artists, their funders, or their communities, it might be an interesting method to consider.