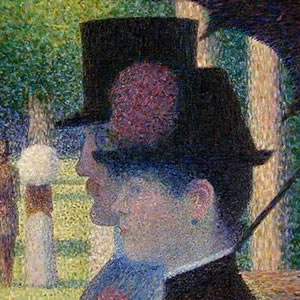

One of the core actions of aesthetic/artistic attention is to step back – to make a little space between yourself and the object of your attention, so you can see it as it is, rather than see it as you are. Stephen Sondheim captures this imperative (and its implications) in “Finishing the Hat” from Sunday in the Park with George (here’s Mandy Patinkin’s reprise of his original Broadway role):

Studying a face

Stepping back to look at a face

Leaves a little space in the way like a window

But to see, it’s the only way to see

In aesthetics, this approach or attitude is called “disinterest,” not because you don’t care about the work, but because you work to remove your immediate self from its observation. As one encyclopedia frames it: “The person who adopts the aesthetic attitude does not view (hear, taste, and so forth) objects with some kind of personal interest, that is, with a view to what that object can do for her, broadly speaking.” Instead, disinterest suspends your individual needs and goals to make space for observing the object or experience more fully.

In aesthetics, this approach or attitude is called “disinterest,” not because you don’t care about the work, but because you work to remove your immediate self from its observation. As one encyclopedia frames it: “The person who adopts the aesthetic attitude does not view (hear, taste, and so forth) objects with some kind of personal interest, that is, with a view to what that object can do for her, broadly speaking.” Instead, disinterest suspends your individual needs and goals to make space for observing the object or experience more fully.

English scholar Edward Bullough framed the same idea (back in 1912), but used the phrase “psychical distance” rather than disinterest. “Distance,” he wrote, “is obtained by separating the object and its appeal from one’s own self, by putting it out of gear with practical needs and ends.” Bullough suggests that a core strength and power for artistic expression and experience is this distance…we can observe intense events on a theater stage and know they’re not real, but also be open to their emotional meaning and consequence [Shakespeare productions in Central Park, notwithstanding].

Disinterest and distance don’t mean “detachment,” which Bullough makes clear: “Distance does not imply an impersonal, purely intellectually interested relation of such a kind. On the contrary, it describes a personal relation, often highly emotionally colored, but of a peculiar character” [emphasis from the original].

Why the aesthetics lesson? Because managers, particularly of cultural organizations, face a similar challenge. They can experience their charge according to their own emotions and needs, in which case they abandon the larger circles of people, purposes, and processes in play. Or, they can experience everything as distant, intellectual, and clinical, in which case they abandon the emotional and human aspects of the enterprise – approaching the organization as if it were a machine. Like Goldilocks, arts managers need to find the psychical distance that is “just right” for resilient and responsive management — not too close, not too far.

Bullough describes two extremes that limit aesthetic engagement: One is “under-distance,” when the artist or observer connects too closely to the work and it becomes entirely about personal pleasure; the other is “over-distance,” when the artist or observer is far afield, making the experience feel improbable, artificial, or empty.

In our quest to professionalize arts organizations and corporatize the selection, evaluation, and training of their managers, we’ve tended to drive toward over-distance. Professionals, we believe, behave in a disinterested way, they approach their job as systems engineers and process improvers. That said, we’ve also indulged our share of under-distanced artistic leadership, where ego and individual whim are signifiers of excellence.

If we are to consider our management and organizational work with a more aesthetic eye, we’ll need to include our own distance as part of the palette. We must learn to step back far enough to see, without ego, what’s before us, but not so far that we lose our human and humane response.