Thanks, Crawl Space. Last show, Stranger Circumstances, opens Nov. 7 at 6 p.m.

Thanks, Crawl Space. Last show, Stranger Circumstances, opens Nov. 7 at 6 p.m.

Main Content

Shadows in art – part 1 of 3

If you drag your life behind you in a sack, it’s your shadow. A shadow is a fact when you cast it and otherwise a metaphor for experience, except in art, where its meanings are myriad.

Cat Clifford‘s shadows do not depend on light. They have their own lives and creatures who move within them.

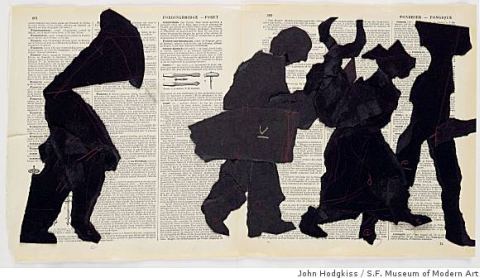

William Kentridge gives flesh to James Joyce’s aside, that history is a nightmare from which he is unable to awake.

William Kentridge gives flesh to James Joyce’s aside, that history is a nightmare from which he is unable to awake.

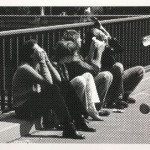

In An-My Le‘s war, soldiers set up shadows to take the hit. (more)

In An-My Le‘s war, soldiers set up shadows to take the hit. (more)

Matt Browning‘s Honest Labor is a droll sham even though it’s real, which is why shadows carry the meaning.

Matt Browning‘s Honest Labor is a droll sham even though it’s real, which is why shadows carry the meaning.

Charles LaBelle‘s shadows accept none of taint.

Charles LaBelle‘s shadows accept none of taint.

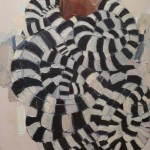

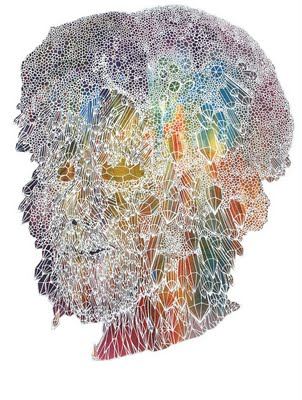

Chris Buening‘s shadows are fractured light.

Chris Buening‘s shadows are fractured light.

Methhead  Said Buening, via Best Of

Said Buening, via Best Of

When I first moved to Seattle methamphetamine was quickly becoming (or perhaps already was) the preferred party drug in the gay scene. I was a working DJ at the time, spinning at clubs and parties around town….Methhead is a memorial for a lifestyle that I left behind years ago and for some of my friends who were lost along the way. I think of the statue-like crystalline head as being symbolic of many different faces / heads, as well as being a kind of self-portrait of that time in my life. I also think that correction fluid (a material generally used for covering one’s mistakes) is the perfect medium for the “portraits” in this series, which often have dark and embarrassing back-stories.

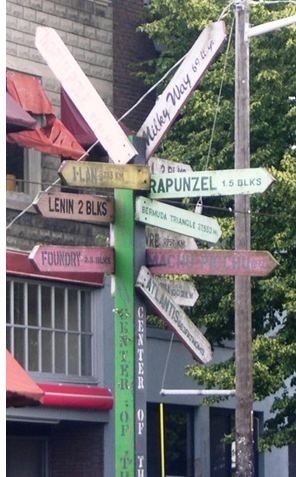

Street signs in Fremont: Lenin to your left

If the Northwest had been in Old, Weird America

It would have been a stronger show.

As it is, The Old, Weird America is a hell of an accomplishment. Its curator Toby Kamps proved that folk themes encased in stereotype can become fluid when reconsidered by contemporary artists.

The 18 featured come from around the country, everywhere but here. Kamps had no responsibility to include all regions. His goal was an alchemical series of relationships, each building from each to enrich the complexity of his themes. Most of what he delivered is magnificent, but there are a few artists hitching a ride on the accomplishments of others. They’re good but not great.

Exhibits are not infinitely expandable. Anyone suggesting an addition needs to propose a deletion.

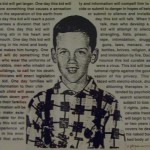

I’d delete none of the following, the exhibit’s A-list heart and soul: Eric Beltz‘s cobwebby drawings of founding fathers; Jeremy Blake‘s video miasmas of memory and loss; Sam Durant‘s revolving stage set that upends a foundational myth; Barnaby Furnas‘ explosive paintings; Matthew Day Jackson‘s Spiritual America collage; Margaret Kilgallen‘s Main Street; McDermott & McGough‘s gay history; Brad Kahlhamer’s lost roots drawn as a stream of consciousness; Aaron Morse‘s woozy scale shifts; Allison Smith‘s self-portraits as Civil War corpses, better in this context than they’d be on their own; Kara Walker’s ecstatic recreation of this country’s original sin, and Charlie White‘s collage photo, revealing everything important about a pivotal American year in the mid-20th Century.

There’s nothing awful about the remaining five, save that their work doesn’t measure up. Had Kamps been aware of what’s going on in the Northwest, he would have made stronger choices. In terms of this show, stronger choices litter the NW ground.

Instead of Deborah Grant’s Where Good Darkies Go (after Bill Traylor), a wall of Marita Dingus’ glass heads would have served the purpose. Next to them, Grant’s work looks academic.

Grant:

Sometimes Dingus’ sculptures have a burrowing mole feeling. Glass gives her focus a point of light, a contrast that functions as an intensifier. Discards are metaphors for Africans who were used as slaves until they were used up and died. Her reuse of their images delivers a powerful new life.

Sometimes Dingus’ sculptures have a burrowing mole feeling. Glass gives her focus a point of light, a contrast that functions as an intensifier. Discards are metaphors for Africans who were used as slaves until they were used up and died. Her reuse of their images delivers a powerful new life.

[Read more…] about If the Northwest had been in Old, Weird America

Deborah Baldwin: the art of the lead

There are points in any life when people burrow. I know I’m in one when I’m reading almost nothing but essays about art with murder mysteries on my I-Pod, the latter to guarantee that as I engage in humdrum tasks, the voice in my head is not my own.

I surfaced into a (slightly) larger world this weekend when I looked up an old friend online and found her writing for Dwell. I don’t care about Dwell, which appears to be fetishistic about the finer points of gracious living, but I do care about leads. My friend, Deborah Baldwin, writes them as well as anybody.

Here she is on getting fired:

When someone gets fired from a French kitchen, the chef de cuisine says simply, “Take your knives.” To a chef, the knife is like an extra appendage, and its dismissal cuts deeper than the standard American “It’s just not working out.”

And on the lost pleasure of coffee shops:

I love coffee. It’s coffee shops I have a problem with. Whenever someone suggests we “grab coffee and catch up,” I instinctively shudder and suggest instead a nice cocktail or root canal.

Once havens for intellectual inquiry and quiet perusal of newspapers, coffee shops are now basically retail outlets and free office space.

Nursing a cappuccino the other day, I observed a frantic businessman conducting a conference call on speakerphone, a woman toting a hysterically yapping Labradoodle, and two frosty socialites loudly debating the relative appeal of the spray-on tan. Kerouac would never have got anything done.

As in art, it’s not the tale but the teller.

Update: Even though the Deborah Baldwin I know writes about food and wry lifestyle, I’m quoting another Deborah Baldwin. Everything’s accurate about this post, except that I don’t know this Deborah Baldwin from Adam. Or Eve.

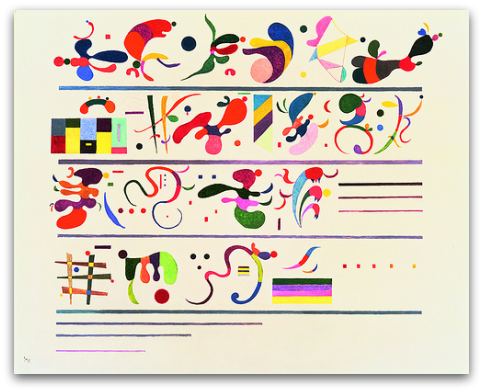

The visual score, after Christian Marclay

Previous post, that ends with Marclay: The visual score, after Kandinsky

Scores that are paintings, drawings and collages are everywhere in recent years. They function as art on their own but can, depending on the performer, inspire sound.

We are all ears.

A few of my favorites:

A few of my favorites:

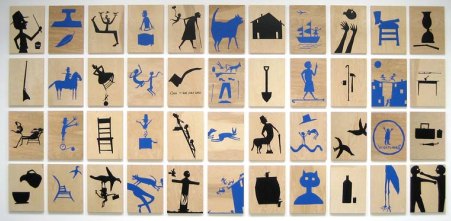

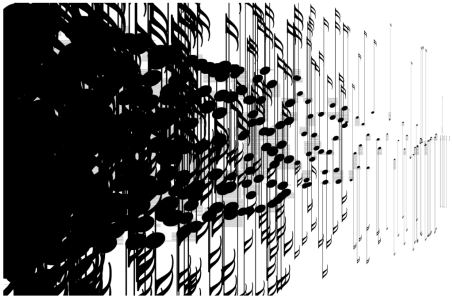

Paul Rucker, Strange Fruit, a score he plays on his cello:

Strange Fruit is part of an exhibit at Cornish College called Live in the Hyphen, with Rucker and Wynne Greenwood, through Oct. 16. Greenwood talks in the gallery noon-1 on Oct. 16.

Strange Fruit is part of an exhibit at Cornish College called Live in the Hyphen, with Rucker and Wynne Greenwood, through Oct. 16. Greenwood talks in the gallery noon-1 on Oct. 16.

[Read more…] about The visual score, after Christian Marclay

She who digs newspapers…

A couch for Pina Bausch

Ulli Weiss photo from Pina Bausch performance

Sean M. Johnson, Family Portrait (Nothing but tape holding it to the wall)

Sean M. Johnson, Family Portrait (Nothing but tape holding it to the wall)

Quote marks in nature

The visual score, after Kandinsky

If you start here

or here

or here

you can stop here

you can stop here

with a leapfrog to Trimpin and Christian Marclay without missing much in between.

with a leapfrog to Trimpin and Christian Marclay without missing much in between.

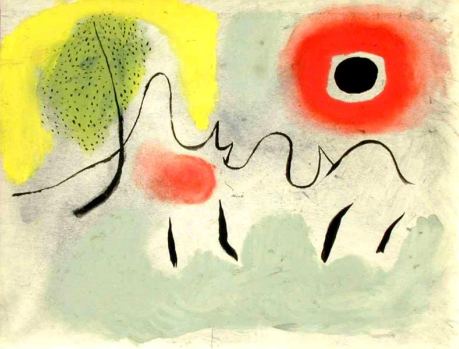

Minus the mysticism, Trimpin and Marclay are as committed as Kandinsky to the visual implications of sound. While many of Kandinsky’s ideas about spiritual color and visual sound found few takers in the second half of the 20th century, they are in play today.

Trimpin– Score for PHFFFT

I remember as a child helping to build huge, wooden discs to set on

fire at night and roll off a ramp to hang in the air and fall into the

valley below, as part of an old German festival. I heard the whistling

and crackling of the wet wood as it rolled down the ramp and thought of

opera. I asked the other boys, `Do you hear that?’ They said no. I like

to think my work enables other people to hear what I hear.

I composed a

silent collage of found film footage partially layered with computer

graphics

to provide a framework in which live music can develop. Moving images

and

graphics give musicians visual cues suggesting emotion, energy, rhythm,

pitch,

volume, and duration. I believe in the power of images to evoke sound.

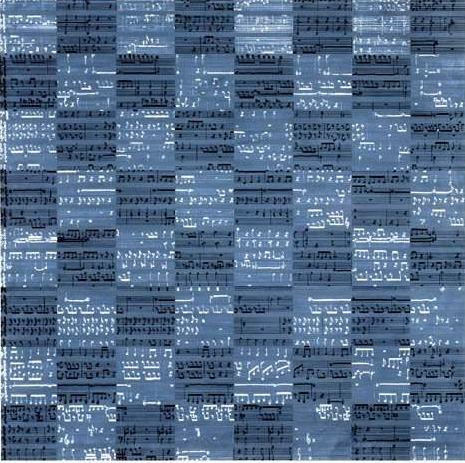

Image from Marclay’s Screen Play