Whence comest thou?

From going to and fro in the earth, and from

walking up and down in it.

Regina Hackett takes her Art to Go

That old grade-school test question - Which of these does not belong? - offers a key to the aesthetics of the expressively hot, as opposed to the classically cool. The hint of crazy within the solid citizen, the blood in the water and the worm in the rose (mortal, guilty) move us in a way that visions of perfection rarely do. In honor of the flaw, a small survey of its recent, robust manifestations. Douglas Gordon Three Inches (Black) 1997 (image via) Susan Robb: Three from the last … [Read More...]

Filed Under: Uncategorized

If human history were underwater, Alwyn O'Brien's ceramic vessels could serve as the bleached bones of the Ancien Regime, the decorative drained and dead on a dark sea floor. 4 Descending Notes 2010 Manganese Clay and Glaze 9" x 7" x 5 1/2" Hand-rolled coils make her lacy vessels. Born past their prime, they are in their own weird way pristine. Story of Looking, 2010 Porcelain and glaze, Two Pieces 12 1/2" x 14" x 5" Following Thelonious Monk, she knows how to use the wrong … [Read More...]

Filed Under: Uncategorized

Collectors who hire experts to solve problems that don't exist till help arrives are responsible for the equivalent of bad face lifts on old masters. What the artists intended too frequently recedes under an abrasive cleaning or a deadening layer of varnish. Current practices discourage irreversible interventions. That means John Currin's work is a little safer than artists who preceded him, such as Picasso, although having the money to buy good advice doesn't guarantee it will be heeded. … [Read More...]

Filed Under: Uncategorized

Nice to see David Wojnarowicz (wana-row-vitch) back in the news, making the monkeys dance. It's no surprise that the usual people want to use their deliberate misunderstanding of his work to rally their frightened base. It's also no surprise that the Smithsonian once again proves to be cowardly. Remember its Enola Gay exhibit from 1995? The examination of this country's use of the Atom Bomb started as scholarly and turned into a my-country-right-or-wrong cheering section, after suitable … [Read More...]

Filed Under: Uncategorized

Humans see, humans do: After the first horse drawn on the first cave and the first pot incised with a decorative line, everything became imitation. You don't need a weatherman to know which way that wind blows, or that in the contemporary period, it blows harder. In selecting the 12 artists featured in Image Transfer: Pictures in a Remix Culture, associate Henry curator Sara Krajewski looked for those whose engagements with image recycling make them visual mix masters of note, those who … [Read More...]

Filed Under: Uncategorized

By Regina Hackett Leave a Comment

Mequitta Ahuja Wriggle, oil on canvas, 41"X26" 2008. Could have been titled, Medusa takes a nap. Geoffrey Chadsey Welterweight, 2002 Watercolor pencil on rag vellum, tape 57" x 24" Another great Chadsey figure with flowing locks. (Not safe for work.) Lauren Grossman Behold 2003 Iron, wool, steel. 13"x21"x12" Rolls on casters. Mequitta Ahuja, again. Flowback, oil on canvas, 68"X51" 2008 … [Read More...]

Filed Under: Uncategorized

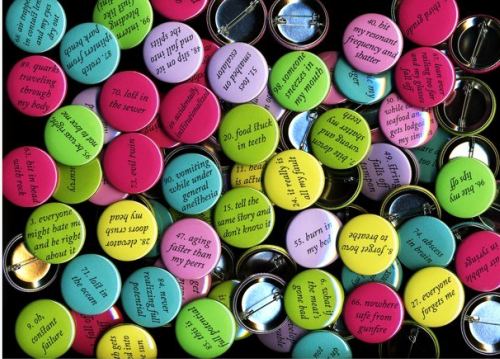

From Jennifer Zwick, image via

Previous in the same vein, Zwick’s 100 Answers To What Might Go Wrong.

Previous in the same vein, Zwick’s 100 Answers To What Might Go Wrong.

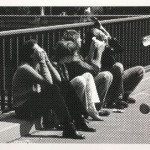

John Sutton, Ben Beres and Zac Culler teamed up ten years ago as students at Cornish College, building a brick wall to block entrance to the faculty parking lot. Their current exhibit at Lawrimore Project gives them a chance to look backward to assess their accomplishments.

The Answer, My Friend…, 2009

Acrylic, electric fans, 56 cubic feet of circulating air

88 x 34 x 34 inches

Every fan whirs away, generating nothing. It’s not easy being the joker in the pack, the sane man in King Lear’s court, the forward momentum surrounded by inertia. Even artists who play it straight are surrounded by what opposes them, be they those rarities encased in success or the more common breed, hearing the echo of their actions bounce off the walls of empty rooms.

Every fan whirs away, generating nothing. It’s not easy being the joker in the pack, the sane man in King Lear’s court, the forward momentum surrounded by inertia. Even artists who play it straight are surrounded by what opposes them, be they those rarities encased in success or the more common breed, hearing the echo of their actions bounce off the walls of empty rooms.

Nobody called, nobody came in, nothing happened, nobody cared if I died or went to El Paso.

Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe, talking to himself in The High Window.

SuttonBeresCuller cannot claim to be talking to themselves. The admiration that is strong in Seattle increasingly extends beyond it. One stage performance which I didn’t see earned them the honor of a take-’em-out review by Jen Graves.

Their response is in the current show. On beach stones they incised every single word.

Crouching down for a better look, I found shallow, hoax and my name, the last because her piece included an attack on me, for this review. (Its headline is unfortunate. Critics employed at newspapers don’t write their own and yet, if their reviews live at all, they live on their headlines.)

Crouching down for a better look, I found shallow, hoax and my name, the last because her piece included an attack on me, for this review. (Its headline is unfortunate. Critics employed at newspapers don’t write their own and yet, if their reviews live at all, they live on their headlines.)

Incised words on stones are a sweetness-and-light stable in gift shops. The art world has even more reason to look favorably on piles of precious things, trained to do so by Felix Gonzalez-Torres. A Dissent is both funny and effective. Change the joke and slip the yoke, what Ralph Ellison called “a kind of jujitsu of the spirit, a denial and rejection through agreement.”

In 2002 at the now defunct ConWorks, SuttonBeresCuller offered a giant pencil suspended from the ceiling which audience members could push in order to draw. When Lawrimore Project opened in 2006, SBC installed it as a stand-alone sculpture.

What a difference a day (or two) makes. Here’s their current version:

What a difference a day (or two) makes. Here’s their current version:

In her review of the current show, a backpedaling Graves noted the work is marked by frustration and exhaustion. To make art about exhaustion is not the same as producing exhausted art. But I digress as well as sympathize. Backpedaling is frustrating and exhausting too.

In her review of the current show, a backpedaling Graves noted the work is marked by frustration and exhaustion. To make art about exhaustion is not the same as producing exhausted art. But I digress as well as sympathize. Backpedaling is frustrating and exhausting too.

Barely in Need, SBC panhandling performance. 2003

SBC’s most ambitious foray into public art, an attempt to turn an abandoned gas station into a park, has been blocked at every turn. And yet, four years in, they’re still at it, with a model of the ultimate result in the show. (My story about the ecological complications here.) They may be insane, but they are not exhausted.

SBC’s most ambitious foray into public art, an attempt to turn an abandoned gas station into a park, has been blocked at every turn. And yet, four years in, they’re still at it, with a model of the ultimate result in the show. (My story about the ecological complications here.) They may be insane, but they are not exhausted.

Onward, into the future.

Flight Path, 2009

Mixed media (always installed facing the highest

concentration of U.S. military forces)

On the same block of Seattle’s Capitol Hill are two galleries that take chances while hedging their bets. Both Grey Gallery and Vermillion are also bars. If

the art doesn’t sell, the drinks will. Even in the current climate,

however, the art tends to move more quickly than in Seattle’s gallery hub in Pioneer Square.

Of the three artists showing currently at Vermillion,

painter Ryan Molenkamp has almost sold out. With one exception, it’s been a long time since that many red dots appeared in the Square.

If I were going to imagine a stage set for college professor’s suburban interior in

mid-20th Century America, I’d put one of Molenkamp’s paintings over the

sofa. The people who lived there would have loved high and loathed low. The abstraction they’d like best would be European, as the New York School would have seemed a trifle crude. Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, showing up later in the decade, would not have qualified as artists at all. Yes to Satie, no to Chuck Berry.

Early in the 21st Century, Molenkamp’s style of painting is most frequently found in Goodwill. What goes around comes around, but possibly because I remember the off-putting originals from my childhood, Molenkamp’s updates are a problem I’m not equipped to solve. He’s a better painter than the anonymous stereotype I have in my head, but that stereotype blocks my view.

Sharon Arnold weaves and cuts with a gentle hand. Because her work evokes more exuberant versions by others, the word that I couldn’t push away is timid.

Sharon Arnold weaves and cuts with a gentle hand. Because her work evokes more exuberant versions by others, the word that I couldn’t push away is timid.

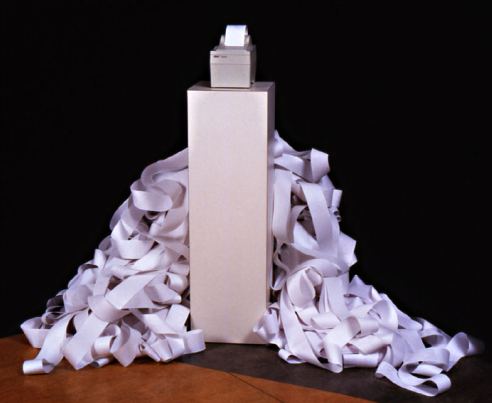

Here’s Claude Zervas‘ version of an adding machine spitting out clouds, from 2002.

Cumulus, Receipt printer, computer, roll paper

48″ x 48″ x 48″ variable

And here’s Arnold’s:

And here’s Arnold’s:

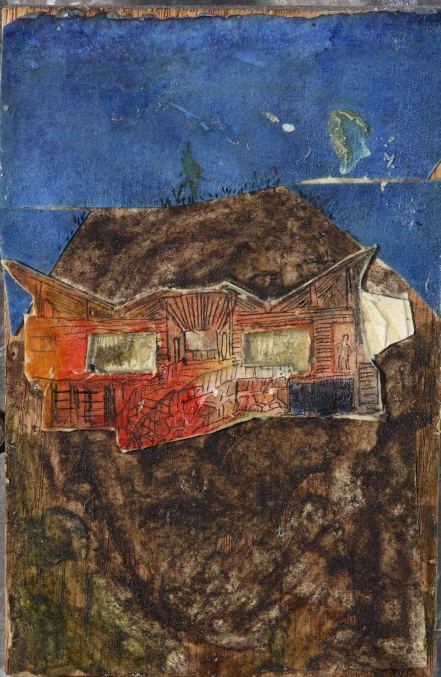

Seattle’s Aurora Avenue and other gateways to marginalized blight have their own poet. Kristen T. Ramirez makes these no-exit avenues of cheap dreams new again. She mines the noisy collision of mid-20th Century textures, colors, styles and cultural contrasts found in America. Ranch-style gas stations, the curving arrows beckoning you in, the birds on phone wires, the invitations to eat cheap, sleep in easy reach of a TV and buy a beater car become a survivalist’s manual for a people’s art form.

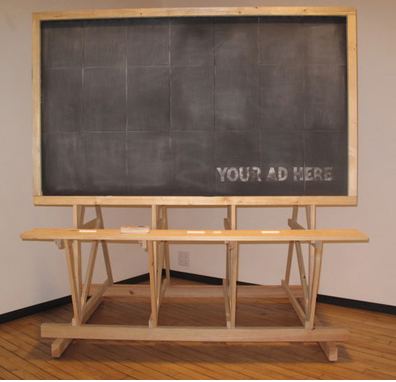

Her collages are her signature, but not her only one. Advertising in other contexts becomes less benign.

Her collages are her signature, but not her only one. Advertising in other contexts becomes less benign.

Incised into bottles are messages pulled from the country’s vast stash of cliches: Up and at ’em.

Incised into bottles are messages pulled from the country’s vast stash of cliches: Up and at ’em.

Ramirez’s Ghosts of Commerce Past is at Grey Gallery through Dec. 5.

Ramirez’s Ghosts of Commerce Past is at Grey Gallery through Dec. 5.

The fluidity in Warren Dykeman‘s paintings does not come from his figures. They are stationary; the footwork belongs to the field. His paintings are about breath. Hanging in the colored air in front of men in hats and horses frozen mid-gallop, breath does not take the form of a comic-book thought bubble or speech. It is an exhale on the beat.

If you want to be surprised by the plot of Nabokov’s Laughter in the Dark from 1938, skip the first two sentences.

Once upon a time there lived in Berlin, Germany, a man called Albinus. He was rich, respectable, happy; one day he abandoned his wife for the sake of a youthful mistress; he loved; was not loved; and his life ended in disaster.

Art is not plot. (Image via)

an ArtsJournal blog