At Elizabeth Leach through Jan. 30. Interview with Christopher about his father, Robert, after the latter’s death in 2008, here. Podcast interview with Eva Lake (30 minutes, worth it), here.

At Elizabeth Leach through Jan. 30. Interview with Christopher about his father, Robert, after the latter’s death in 2008, here. Podcast interview with Eva Lake (30 minutes, worth it), here.

Main Content

Buddha mind & sliced ham

Philip McCracken, Buddha’s Mind (Via) – Eternity as dinner

The Northwest School – always in session

As long as artists are using your work, you’re not dead.

Leo Kenney, Formation No. 4, New Center, 1966 (At Seattle artREsource)

Jeffrey Simmons, Proxima, 2008 (At Greg Kucera)

Jeffrey Simmons, Proxima, 2008 (At Greg Kucera)

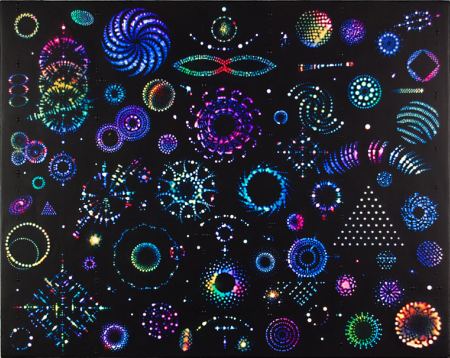

Susan Dory – the pulse of electronic color

Susan Dory‘s paintings could not have existed before satellite transmissions, personal computers and cell phones. Like Tim Bavington‘s, her color sense is electronic. But while his stripes relate loosely to musical tones, her horizontal pulses appear to be celestial. When sending messages to galaxies far, far away, we could code them on her color wheel. There are worse ways of saying hello.

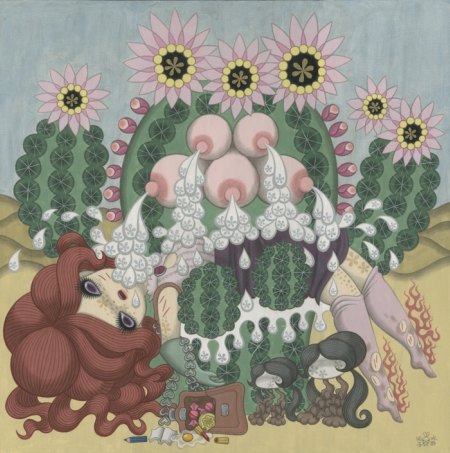

Junko Mizuno milks it

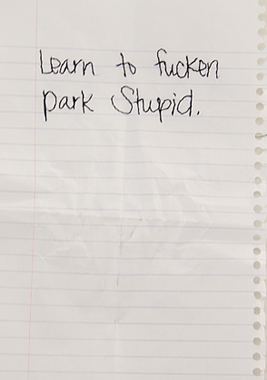

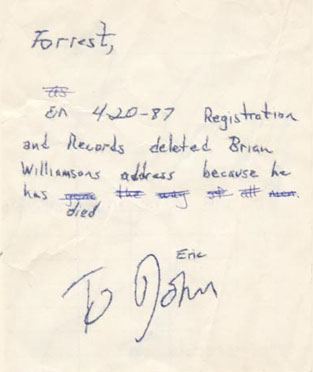

Marc Dombrosky – what’s new in castoffs

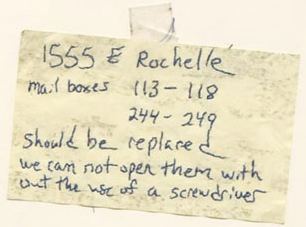

Post-It Notes are raw material for Marc Dombrosky, and so are notes on the backs of envelopes, receipts and letters. He cares about what people want to remember after they’ve forgotten it. Dombrosky is the kind of person who does not look up. What interests him is on the ground. When a written fragment speaks to him, he takes it home and reinforces the text by sewing over the script.

With homespun domestic skill, he returns trash to the bosom of the family. Lost or tossed messages are upgraded into a kind of street poetry.

Lately, Dombrosky has moved beyond saving the written word to saving thrown-away tarps and corny t-shirts. Beside eroded gold lettering, King of Pop, is a hand-embroidered black mass: The King of Pop develops a goiter.

Lately, Dombrosky has moved beyond saving the written word to saving thrown-away tarps and corny t-shirts. Beside eroded gold lettering, King of Pop, is a hand-embroidered black mass: The King of Pop develops a goiter.

Dombrosky’s Neverland at Platform Gallery through Feb. 20.

Dombrosky’s Neverland at Platform Gallery through Feb. 20.

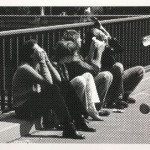

Amir Zaki – lifeguards missing from their station

In college in the late 1960s, a friend of a friend knew a guy named Fred. Thanks to Fred’s bad luck, his fame spread beyond his immediate circle. He walked into an elevator that wasn’t there and had to be rescued, clinging to the cables. If he was on a bus, it broke down. A teaching assistant lost his research paper. There were no copies. He went fishing, and his girlfriend’s hook snagged his cheek.

Rumor had it that Fred carried Kenneth Fearing’s Dirge in his pocket.

1-2-3 was the number he played but today the number came 3-2-1;bought his Carbide at 30 and it went to 29; had the favorite at Bowie but the track was slow–

One day, Fred’s fortunes rose. He had scored a summer job as life guard at a posh LA hotel. The pay was great, the work light and the atmosphere relaxing. What could go wrong? On the first day, arriving as dawn broke, he found a corpse floating face down in the water. Because he failed to jump in to check for vital signs, he never got a chance to sit in the life guard station.

Looking at Amir Zaki‘s digitally manipulated and color-saturated photos of life guard towers in L.A., Fred came to mind.

Not only is no one there, no one could be there.

Not only is no one there, no one could be there.

They are cool-school emblems of futility, a perfect match for Raymond Chandler’s view of swimming pools, a world away from David Hockney’s:

They are cool-school emblems of futility, a perfect match for Raymond Chandler’s view of swimming pools, a world away from David Hockney’s:

Nothing is emptier than an empty swimming pool.

At James Harris Gallery through Feb. 20

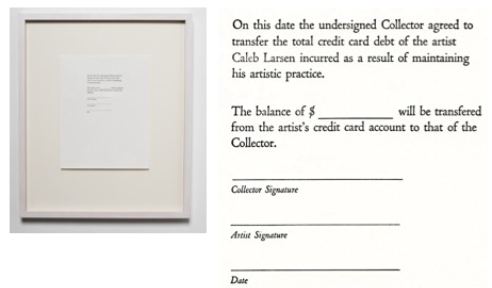

Caleb Larsen – art as transactional residue

Calvin Coolidge

The business of America is business.

Andy Warhol

Making money is art and working is art and good

business is the best art.

Caleb Larsen

Pay my (art-related) credit card debt.

the 1970s, Sol LeWitt placed a drawing in a box which he buried and

wouldn’t say where. The absence of the drawing did not deter its sale,

in the form of a certificate of ownership. If the same reasoning

applied to cars, you could pay for the car and ride away on the credit

card receipt. Unlike war, cars, cats, weather and the kitchen table,

art still functions even if it’s only in the mind.

All art has its own niche. Larsen has staked his in a narrow band of comic process.

A Tool To Deceive And Slaughter

is a black box that will always be attempting to auction itself off on

eBay. The collector who acquires it has to agree to relinquish it if

another offers a bid higher than the owner’s purchase price, and so on,

forever. It’s an answer of sorts to Robert Morris’s Box With the Sound of Its Own Making from 1961, owned by the Seattle Art Museum. Larsen’s is a box with the sound of its own selling.

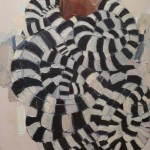

The Entire Contents Of The Pen

The Entire Contents Of The Pen

(1,604 Linear Foot Drawing). Starting with a fresh fountain pen, Larsen

drew on an 9 x 12 inch piece of paper until the pen ran dry.

The drawing now contains everything that the pen once was.

Looks a bit like a Clyfford Still, updated by means of an obsessive-compulsive back story and, of course, the pen.

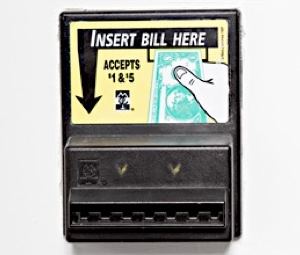

My favorite

My favorite scam

sculpture in the show is titled, $10,000 Sculpture (In Progress). It

accepts your money, and gives you nothing back. I slipped it three

dollar bills before coming to my senses. When there is so much in life

that disappoints in spite of our best efforts, it is positively

exhilarating to volunteer to be scammed, eyes wide open.

At Lawrimore Project through Feb. 13.

At Lawrimore Project through Feb. 13.

Gary Snyder & the Tire Truck Buddha

Tire Truck Buddha by NameTheRabbit via deviantART (Thanks, Paul O’Neil)

Gary Snyder, from Mother Earth: Her Whales

Gary Snyder, from Mother Earth: Her Whales

And Japan quibbles for words on

what kind of whales they can kill?

A once-great Buddhist nation

dribbles methyl mercury

like gonorrhea

in the sea.

…

Ah China, where are the tigers, the wild boars,

the monkeys,

like the snows of yesteryear

Gone in a mist, a flash, and the dry hard ground

Is parking space for fifty thousand trucks.

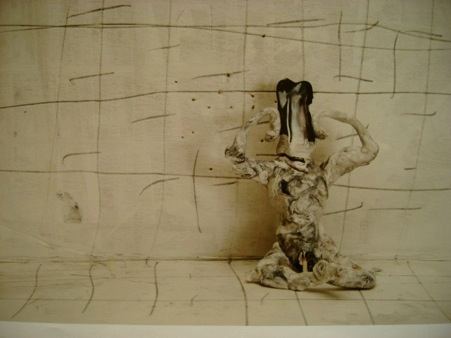

Doug Jeck loves you. No, really

On a battered trunk sits a TV set so old and ugly it would get tossed from a donations box. When it’s plugged in, the screen lights to bluish-white and black static. Through its haze appears a head-and-shoulders shot of University of Washington art professor Doug Jeck, the terror of undergraduates. His big fake nose makes him look like a forlorn, featherless parrot. Covered in ceramic dust, he sings I Will Always Love You in a trembling falsetto.

My brother once owned a dog who could sing like a saxophone. Trying to encourage a performance, I half-crooned a howl to get him in the mood. Nothing. “You have to put your heart in it,” my brother said.

My brother once owned a dog who could sing like a saxophone. Trying to encourage a performance, I half-crooned a howl to get him in the mood. Nothing. “You have to put your heart in it,” my brother said.

Jeck puts his heart in it. Even if he’d never made anything else, for this one piece (Pathetique, 2003) he’d deserve a place in art’s memory bank.

But that’s not all. Jeck’s After Muybridge 2007 – suite of 9 photos of clay figures morphing from one frame to another – hangs on a wall.

Muybridge documented motion and Jeck breakdown. There’s a foolish attempt to rise again in the final frame, a burnt offering. Jeck’s figures lack the resilience of Thomas Schutte‘s lumpen freaks from, for instance, United Enemies. Instead, the Seattle artist parodies American individualism. His tiny people are masters of their own ships and captains of their own souls with nowhere to go and no way to get there.

Muybridge documented motion and Jeck breakdown. There’s a foolish attempt to rise again in the final frame, a burnt offering. Jeck’s figures lack the resilience of Thomas Schutte‘s lumpen freaks from, for instance, United Enemies. Instead, the Seattle artist parodies American individualism. His tiny people are masters of their own ships and captains of their own souls with nowhere to go and no way to get there.

Jeck is part of Wet and Leatherhard at Lawrimore Project, curated by Susie J. Lee. Instead of final products, Lee looks at process, at what a devotion to the muck of the earth does to contemporary artists.

Photos and a video document a 1972 performance by Jim Melchert and his friends. They stuck their heads in buckets of wet clay and waited for it to dry. Kristen Morgin recreates old tin toys with unfired replicas, the new far more fragile than the old. Wynne Greenwood‘s attempts at a vessel wouldn’t pass muster at summer camp, yet like the obese in bikinis, their bloated splendor insists on attention.

For Tim Roda, Meiro Koizumi and Ben Waterman, clay is a prop for performance. For Sterling Ruby, the ultimate performance cannot be controlled. It’s what happens in the firing. Artists make offerings, and the kiln decides who is Cain and who is Abel.

Through Feb. 13.

Through Feb. 13.