Main Content

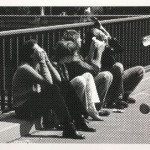

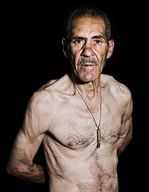

Jesse Burke – the men around us

Santiago Sierra failed make a dent on the politics of economic power when he paid a pittance to unemployed young men to allow tattooed line to be permanently inscribed across their backs, like a scar from the lash of a whip.

From ARTnews:

From ARTnews:

Often working with refugee organizations, Sierra created pieces that involved workers from the local underclass being paid to do meaningless tasks: support a piece of Sheetrock at a 65-degree angle for an entire day; sit inside a cardboard box; or push around two-ton blocks of concrete. By designing such deliberately pointless “jobs,” he highlighted the disjunction between such workers and their work, showing labor as an imposed condition rather than a choice one makes. “The remunerated worker doesn’t care if you tell him to clean the room or make it dirtier,” Sierra remarks. “As long as you pay him, it’s exactly the same. The relationship to work is based only upon money.”

Degrading work is based only on money. By offering only degrading work, Sierra epitomized the problem. His reputation soared, but it’s doubtful his collaborators look back on their participation with pride.

What is exploitation? In the 1980s, many critics claimed that to photograph the homeless at all is to exploit them. Saner voices now prevail, but it’s hard in such work to avoid the didactic or sentimental.

Jesse Burke scores a poignant success in Low at Platform Gallery. Burke paid a group of homeless men to come to his studio, take off their shirts and be photographed. (Click to enlarge.)

In the early 1980s, visiting a friend who’d moved to the lower East Side prior to its upgrade, I noticed watery blood stains in snow drifts. I asked if they documented fights from the previous night. No, said my friend. They mark places that the homeless relieve themselves.

In the early 1980s, visiting a friend who’d moved to the lower East Side prior to its upgrade, I noticed watery blood stains in snow drifts. I asked if they documented fights from the previous night. No, said my friend. They mark places that the homeless relieve themselves.

I thought of that exchange when looking at Burke’s photos. The men in them aren’t pathetic or heart-warming or instructive. They do not go forth and teach all nations. Instead, they are simply and clearly a genuine measure of themselves. To June 20.

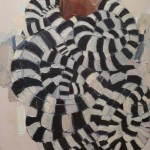

Noah Grussgott: You are the chair

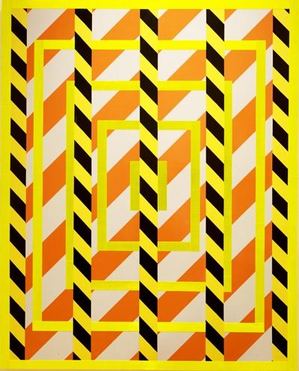

Doing the dog paddle, some people think they’re Esther Williams. Noah Grussgott lives in the gap between fact and optimistic fantasy. His chairs that are figures are made from material signs of distress (barricade tape, band aides, crumbling bits of brick wall and discarded foam core), but they occupy space with a jaunty elan. They are the best news they’ve ever heard.

Gathered together in Bleacher, they project a comic air of expectancy: Whatever is going to happen is going to be good.They are not troubled by their lack of forward momentum. Why travel when you’re already there?

Gathered together in Bleacher, they project a comic air of expectancy: Whatever is going to happen is going to be good.They are not troubled by their lack of forward momentum. Why travel when you’re already there?

Band aide chair:

Barricade tape chair: Although it’s an insufficient image, I love the cheap charm of his baby blue/girly pink foam core Frank Stella, on the wall below.

Although it’s an insufficient image, I love the cheap charm of his baby blue/girly pink foam core Frank Stella, on the wall below.

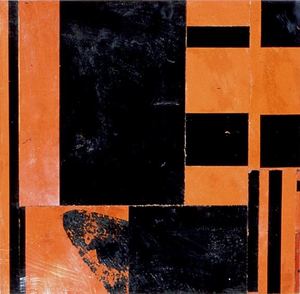

Robert Yoder’s battered geometries from the 1990s….

Robert Yoder’s battered geometries from the 1990s….

look positively regal next to Grussgott’s.

Although Yoder is almost always purely abstract, he has the weight to sound a serious depth. I’m not sure the same can be said of Grussgott.

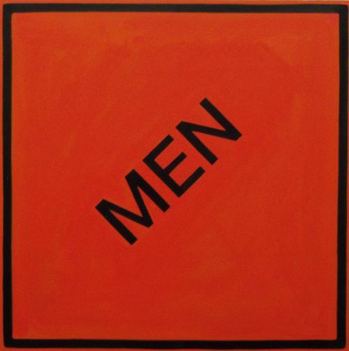

I used the swastika as a literal symbol, immediately recognizable as a

representation of hate. It’s both in a vulnerable/boxed in position as

well as at the center of the image. The intention was to simultaneously

discuss the ways in which symbols are sensitized and how overtime, even

a swastika can become a cliche.

But swastikas are not cliches. John Updike once wrote that what interests Saul Bellow does not appear to interest his characters. There’s a similar disconnect between what Grussgott wants to convey in his work and the work itself. As long as he stays away from ultimate evil, which swamps him, there are worse problems. In the end, who cares what the artist was thinking?

Grussgott continues at Grey Gallery through June 6. In the Seattle Times, Rachel Shimp sees the show as the artist wants it to be seen.

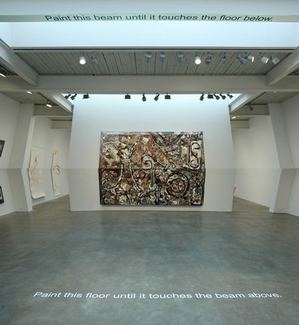

Claim that space – Carl Andre and Charles Ray to Alex Schweder

Carl Andre doesn’t think of his floor pieces from the late ’60s as flat. They claim the space above them to the ceiling.

In 1987, Charles Ray found a more literal way to connect within the spacial void. Ink Line flows from the ceiling to a hole in the floor, refabricated for his current exhibit at Matthew Marks. (Ken Johnson review here.)

Alex Schweder connects through directions, which are, in the photo below, painted at the room’s top and bottom.

Jan Fabre/ Troubleyn – Orgy of Tolerance

At On The Boards Saturday and Sunday.

What a waste. Jan Fabre’s splendid company saves him from the didactic tedium of his text, but just barely.

I think he was going for something like this, Jean Lowe’s Overstock! from 2009,

(Enamel on panel, 95 ½ x 84″)

The fatal virus of consumerist capitalism kills its host.

Instead, frantic overkill subverts his indictment of high fashion, Christianity, the id of appetite, the KKK, Abu Ghraib, racism and the wealthy. Fabre is a leftist blowhard who charms radiant performers into working for him.

Instead, frantic overkill subverts his indictment of high fashion, Christianity, the id of appetite, the KKK, Abu Ghraib, racism and the wealthy. Fabre is a leftist blowhard who charms radiant performers into working for him.

There are moments, however, when the text scores. Men with guns lounge on leather sofas and summon women with a snap of the fingers, who rush over to masturbate them.

“My museum is getting too small for all my Hindu Indians,” says one man. “I need only two more Jews to complete my collection,” says another.

Faber also succeeds in taking the erotic out of the sexual and the fun out of a joke. Orgy of Tolerance opens with four writhing under the pressure of their own hands, coached by four in paramilitary garb. The first 10 seconds were pretty funny, but Farbre skillfully turned the humor inside out to mock those in the audience foolish enough to laugh.

I love this company. They can do anything. Too bad they’re doing this for one hour and 45 minutes. Anytime there was music (Dag Taelderman) and dance, the bad time I was having became a distant memory. The ballet with shopping carts was wonderful, and performer Goran Navojec sold every scene in which he appeared. He’s the only hefty body on the lithe team, and the only one whose sex appeal could not be disguised. Even when he wandered in wearing nothing but diapers and smoking a cigar only to disappear again, he was the star.

I love this company. They can do anything. Too bad they’re doing this for one hour and 45 minutes. Anytime there was music (Dag Taelderman) and dance, the bad time I was having became a distant memory. The ballet with shopping carts was wonderful, and performer Goran Navojec sold every scene in which he appeared. He’s the only hefty body on the lithe team, and the only one whose sex appeal could not be disguised. Even when he wandered in wearing nothing but diapers and smoking a cigar only to disappear again, he was the star.

I heard a woman behind me whisper to her companion, “Bring back the big guy.” Amen.

Artists who fear failure don’t get anything done

An inspiring way to start the day can be found at FAIL Blog. It tracks those who fail big, fail fast and fail often.

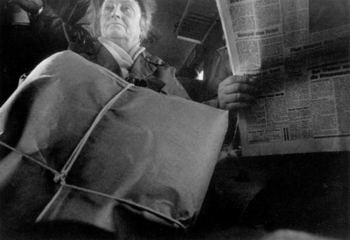

Ursula Arnold – newspapers in the old world

Via, 1966

Alice Tippit – street sign (caution)

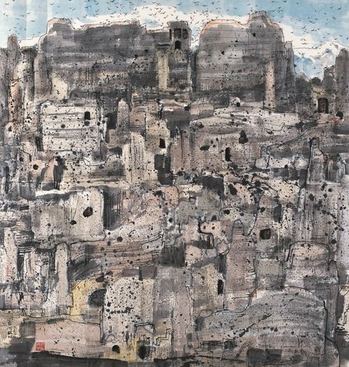

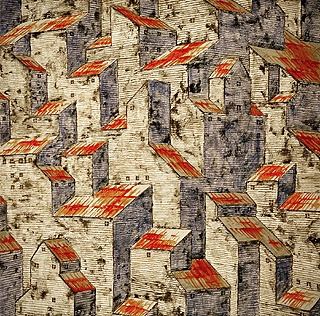

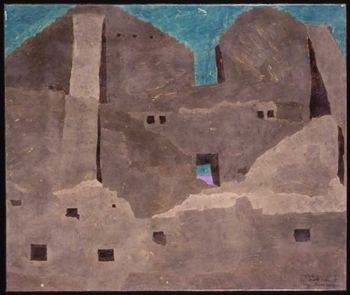

Wu Guanzhong: abandoned places, isolated lives

Good NYT story today by Sonia Kolesnikov-Jessop on the great transitional figure of Chinese art, Wu Guanzhong, now 90. Online, it ran with no images, which is bizarre but still a frequent enough occurrence in newspapers that it goes largely unremarked. A visual art review devoid of images is like a diving suit without an oxygen tank.

What has always struck me about Wu’s work is his tenderness for lost things. Below, The Ancient City of Jiaohe, from 2007, via.

Joseph Goldberg, Wall Ghosts, 1999

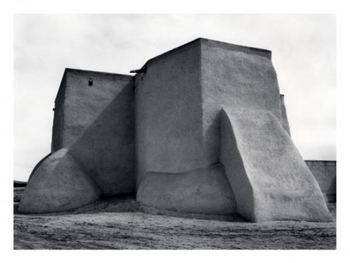

Ansel Adams, St. Francis Church, 1929,

Ansel Adams, St. Francis Church, 1929,  Georgia O’Keeffe, Ranchos Church No. 1, 1929

Georgia O’Keeffe, Ranchos Church No. 1, 1929

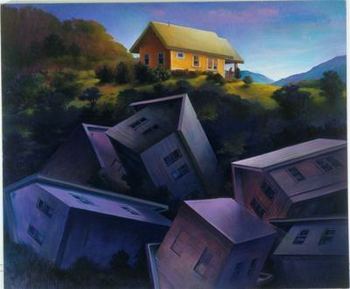

Jay Steensma, Landscape, 1991

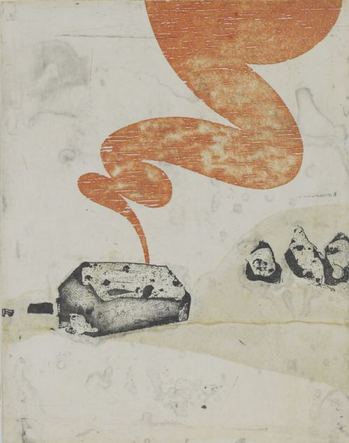

Jeremy Mangan, The Little One, 2009

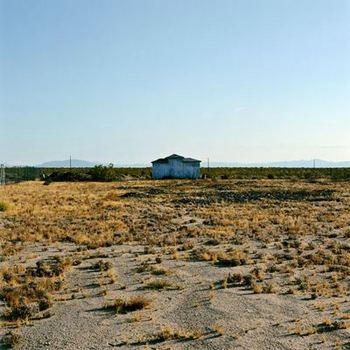

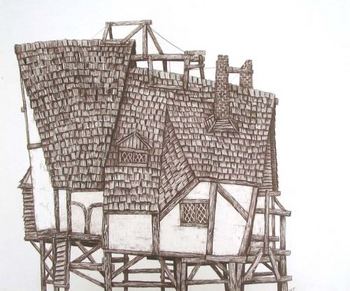

Whiting Tennis, Stranded Tudor, 2009

Whiting Tennis, Stranded Tudor, 2009

Gary Faigin

Gary Faigin

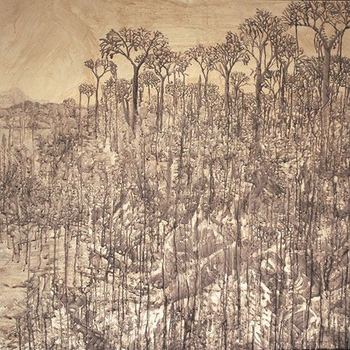

Jesse Paul Miller, Landscape, 2007

Life notes – Vermeer to Chuck Berry

The proliferation of art writing around the country, covering the local and aspiring to the global, makes fully-staffed art sections of old newspapers look sparse indeed. What’s rare are blogs devoted to a single artist that have an authentic voice and distinct point of view, not fan notes but life notes centered on a singular art experience, and how that experience unfolds in a life.

Two of my favorites could not be more different. Jonathan Janson’s Essential Vermeer is a scholarly dissection of every aspect of the painter’s work and the context in which he made it. Janson can truly say he has thought of everything. Peter O’Neil’s Go Head On! The Art & Rock & Roll of Chuck Berry is O’Neil telling his life story through his reaction to Berry’s work. In his own way, O’Neil too has thought of everything.

Disclosure: Peter’s my brother-in-law. I remember trying to argue with him once that Earth, Wind & Fire Blood, Sweat & Tears was better than Sly Stone. (Peter’s correction. It never ends, him being right.) Peter was 14, and I was in my mid-20s. He stomped me speechless. In the end, all the cards were in his hands. I was getting a master’s degree, and he was a 9th-grade drop out. How could this be?

One of his sisters emailed me a couple of days ago to say she didn’t have time to read my blog anymore, because she’s reading his. I guess she has a one blog limit. Those who have a one blog limit might consider joining her. I’ll understand.