Main Content

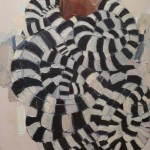

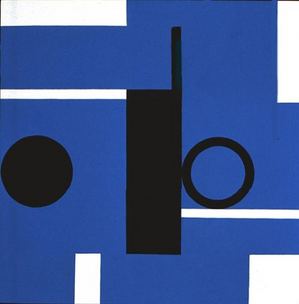

Seattle painter Mary Henry (1913-2009): Began career in her 70s

(Click images to enlarge. Portrait of Henry by former PI photographer Grant Haller. Paintings from Howard House.)

Art likes to contradict itself. Both voluptuary and ascetic, it revels in the sense world yet honors rigor, leads you astray and points to higher ground.

Its rules are made to be broken. Because those rules favor the young, unknown older artists who come on strong are particularly appreciated. Their example derails careerist thinking and restores a sense of possibility.

Few artists came on stronger in Seattle than Mary Henry, who died yesterday at age 96. An abstract painter who produced tough geometric forms filled with bright yet sour tonalities, she lived her last decades on Whidbey Island.

Few artists came on stronger in Seattle than Mary Henry, who died yesterday at age 96. An abstract painter who produced tough geometric forms filled with bright yet sour tonalities, she lived her last decades on Whidbey Island.

In summer her garden was a sight to see, and she tended it largely by herself until recently.

In a 2001 interview, she told me the place was all grass when she bought it.

I was only 60,

so I was able to do a lot of digging. I put everything in, from trees

and shrubs to flower beds. Someone helps me by mowing and trimming the

shrubs. I don’t do it all alone. I garden in the summer and paint in

the winter. The rest of the year, it’s a little of each.

She left golden grass growing in silky clumps in her meadow. Everything else, she put there: water lilies on her

pond; giant rhododendrons on gently rolling hills; beds of blue

bonnets, fragrant lavender and pink, papery poppies; wine grapes on

trellises; flowering plum and apple, and wild, yellow roses leaning out

into the light from tops of trees.

Born in Sonoma, California, Henry worked as a muralist on the Federal Art Project during the Depression and studied with the Hungarian designer-photographer Laszlo Moholy-Nagy at the Institute of Design in Chicago.

She married, had two children, stopped and started painting repeatedly, with little encouragement or notice.

It’s a fairly normal curve for women artists, especially women of her generation, circumscribed by paternalistic dismissal and then clobbered, like everyone else, by the catastrophes of aging. But instead of fading into her seniority, Henry surfaced in her mid-70s with triumphant, joyful work.

It grew directly from her experience at Chicago’s Institute, known as the New Bauhaus after the famous German institution that sought through abstraction to join the worlds of the spirit and the everyday.

Her work derives from…

[Read more…] about Seattle painter Mary Henry (1913-2009): Began career in her 70s

Drooling into art, part 2

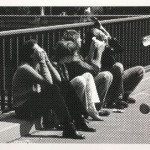

To recap: Santiago Sierra vs. Zhang Huan

(Related posts here and here.)

Both artists engaged members of the hardcore unemployed in performances. But Zhang joined them, and Sierra did not. That’s Zhang in the center on the pond, carrying a child. Had Sierra tattooed a line across his own back and made room for himself in the lineup, his work would resonate instead of grate. He wants to grate, however. Haughty is a big part of his package.

Museology students answer back

In response to this post, (my advice: ashes, ashes; all is ashes), graduate students in the University of Washington’s department of museology responded. Go, you guys. More about this class experiment here.

Whitney Ford Terry:

I feel compelled to mention that an M.A in Museology isn’t just a credential. I don’t feel all together

threatened by the current job market, in fact I think it has allowed

for people to truly realize the importance of restructuring cultural

institutions.If you know what your doing, and you do it well, you’ll find a good

job. Though this may be idealistic – I really do believe it to be true.Thanks for the advice but I think this one is f*cked.

K.C. Porter:

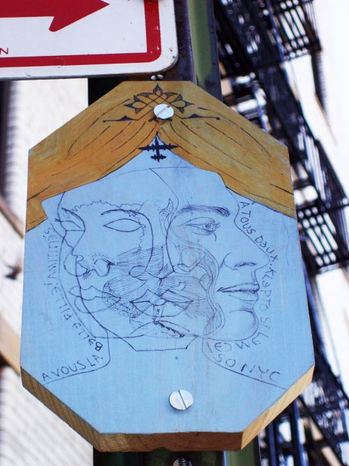

Anatomy of a street sign

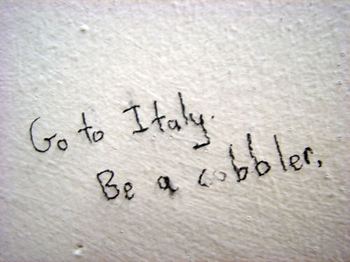

Museology graduate students seek advice

With museum jobs as scarce as truth and justice from the Bush administration, my advice is, do not go into debt getting a credential for a job that isn’t there.

More general life advice is also welcome. All entries will comprise an exhibit at the University of Washington. Details here.

More general life advice is also welcome. All entries will comprise an exhibit at the University of Washington. Details here.

Men around us #2 – labor, economics and class

(Men around us #1 here.)

Zhang Huan: To Raise the Water Level in a Fishpond, 1997, performance, Beijing

I invited about forty participants, recent migrants to the city who had come to work in Beijing from other parts of China. They were construction workers, fishermen and labourers, all from the bottom of society. They stood around in the pond and then I walked in it. At first, they stood in a line in the middle to separate the pond into two parts. Then they all walked freely, until the point of the performance arrived, which was to raise the water level. Then they stood still. In the Chinese tradition, fish is the symbol of sex while water is the source of life. This work expresses, in fact, one kind of understanding and explanation of water. That the water in the pond was raised one metre higher is an action of no avail.

In old communist China, there was little freedom but there was work guaranteed, along with a rough version of a safety net for the compliant. In post-communist China, freedom is given or taken away on the whim of the state. Thanks to capitalist inroads, there is no safety net. It’s a new world of totalitarian capitalism: all risk and few freedoms.

To Raise the Water Level in a Fishpond features the victims of the new economy. They are workers for whom there is no work. They raised not just the water level but the profile of all the left-over and displaced workers around the world.

As John Perreault wrote in another context, capitalism is global, but so is tuberculosis.

Zack Bent and the problem of the Boy Scouts

The Boy Scouts are not a problem for J Zack Bent, who created his 4Culture exhibit – Buffalo Trace – to honor his family’s life in scouting. From the press release:

Zack Bent’s father was a Boy Scout within the Buffalo Trace Council in southern Indiana. “The tradition of scouting was handed down to me by him. And like the true Buffalo Trace, which was a migratory buffalo path through Kentucky, Indiana, and Illinois that acted as road west for early Americans, scouting bears its trace in my life.”

Bent’s photos and relic-like objects document the wry and absurdly tender process of himself, his pregnant wife (the artist Gala Bent) and two young sons diving into the scouting life.

There are, however, children involved. What do they learn from scouting?

1. Homophobia. The organization is on the wrong side of history. If this were the only problem, I’d want its governing board to rot in hell, but there’s more.

2. Anti-eco greed. Just before my newspaper folded last March, PI reporter Lewis Kamb documented that Boy Scouts higher ups across the country for decades have conducted high-impact logging on tens of thousands of acres of forestland, often for the love of a different kind of green: cash. (Three-part series here.)

3. War mongering. See yesterday’s New York Times’ story, Scouts Train to Fight Terrorists, and More. After reading it, art blogger James Wagner had the following, silver-lining thought:

Should we be grateful for one small favor? I mean, as homos we are fundamentally excluded from BSA membership, which normally means no participation in any of their fun and games or lovely overnights, so at least the Boy Scouts of America and their affiliate, the coeducational Explorers program, aren’t teaching violence, militarism, xenophobia, racism and fascism to our own young people (or at least not to those boys and girls who dare to be out while teenagers). (More here.)

Back to Bent. He won me over. I think he’s seriously wrong on this issue, but it isn’t his job to be right. The Boy Scouts are at the heart of his experience, which was in his case positive. Not only is he entitled to his memories, he’s able to turn them into doors that invite even the most alienated to walk through.

On the other hand, the uniforms chill me.