Main Content

Robert Colescott – the Seattle years

Robert Colescott (1925-2009) was a trim, soft-spoken man with a halo of white hair on his handsome head. His manners were courtly, his eyes appraising. He could walk into a room and take everything in. He knew the dirt and failed to hold a grudge.

Ode to Joy (European Anthem),1997

(Via NYT)

As a young painter, he lived in Seattle and found it comfortable but provincial:

As a young painter, he lived in Seattle and found it comfortable but provincial:

Influences came in slowly but didn’t mature and go back out again.

He had just graduated with an MFA from UC Berkeley and had spent a year in Paris studying with Fernand Leger.

Married, Colescott had a young child and another on the way.

While white graduate students at the time easily secured employment at colleges and universities, nothing turned up for him.

I was in a sense more qualified than my peers. None of them had studied with Leger. Why wasn’t I hired? There’s the obvious reason, but I wouldn’t want to guess.

After coming up empty on the college level, he papered the country’s high schools and junior highs with teaching applications. A junior high in West Seattle finally called. Eventually, he taught there and in a junior high on Queen Anne.

I was a mail-order bride, shipped to Seattle.

Although he felt isolated and could never get used to the damp weather, he made a number of important friendships here, especially with the late painter William Ivey.

I hate to talk about him in the past tense. Bill and I sat up nights thrashing out issues of representation. He may well have been as much of an influence on me as anybody.

When Colescott left, it was to teach at Portland State University in Oregon for nine years.

He was probably happiest in Arizona on his own five acres of desert, the proud father of five children.

I hope when they think about me, they think about what I’ve been able to do against certain kinds of odds.

For most of his career, being black in the art world was like riding a bicycle in a swimming pool. No matter how good the swimmer, it’s tough doing laps on a bike.

When the issue came up at all, curators, dealers, collectors and critics could be counted on to affirm their high-minded commitment to quality in art, regardless of the race or sex of the maker.

And yet in overwhelming numbers, the artists in the forefront continued to be white males. White females came next and people of color far in the rear.

Even though white is no longer always right in art circles, Colescott made his reputation before that change.

What’s more, he achieved a position in New York during a time when being from the West Coast was almost as bad as being black.

I had the idea of the moment. I worked it out in Seattle and it took me places.

That idea was straightforward.

Red Box Pictures

Four (ace) former Seattle PI photographers are in business as Red Box Pictures: Scott Eklund, Andy Rogers, Rob Sumner and Dan DeLong. (Blog here.)

Their past gave them their moniker.

Speaking of tattoos – Marilyn Lysohir

Speaking of clouds – Sean Higgins

James Turrell & Dale Chihuly – the brains and body of colored light

Below, a child greets the light in James Turrell’s Skyscape at the Henry Gallery. (Image from the Henry Gallery’s flickr pool.)

James Turrell likes to describe his grandmother telling him that the point of silence for Quakers was to “go inside and greet the light.” Nobody in Dale Chihuly’s childhood asked him to greet the light. With his brother and father dead by the time he was in his mid-teens, his mom had a bar she frequented whose exterior bled neon colors in the night rain. He remembers being happy she was having a good time.

James Turrell likes to describe his grandmother telling him that the point of silence for Quakers was to “go inside and greet the light.” Nobody in Dale Chihuly’s childhood asked him to greet the light. With his brother and father dead by the time he was in his mid-teens, his mom had a bar she frequented whose exterior bled neon colors in the night rain. He remembers being happy she was having a good time.

I once asked Henry senior curator Elizabeth Brown what she thought of a comparison between Turrell and Chilhuly. She told me she thought nothing about it, because they “have nothing in common.”

Nothing? Nothing but the bottom line. They both deal with colored light.

Turrell comes out of Southern California’s minimalist movement and Chihuly out of decorative arts, a field that modernism rejected and Chihuly helped bring into the postmodern mainstream.

Nobody mistakes Chihuly’s work for a church, unless it’s the church of whoopee.

He gives shape to excess and makes it shine. Turrell dematerializes the object, and Chihuly makes a fetish of its production. Next to Turrell’s aesthetic virtue, Chihuly’s vulgarity is startling, but at his best, he has his own kind of virtue.

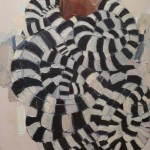

On the black surface of a glass pond (Milli Fiori) flowers bloom. There are water reeds, swamp grass, irises and lilies; water snakes and coconuts, heavy orbs with bright shining wings.

Chihuly celebrates the physical, and Turrell the mental. If Chihuly’s work were a fictional character, it would be Falstaff. Turrell is Prospero.

When Prospero says, “Our revels are now ended,” he’s relieved. Revels are not his thing. Asking Falstaff to tone it down is like like asking Beyonce to join a convent.

Audiences for Turrell and Chihuly diverge. They are each other’s road not taken. What if these audiences woke one day transported to where they never wanted to be, on Turrell’s high or Chihuly’s low? Would they afterward see the world with new eyes or be freshly confirmed in what they felt all along?

Scott Cahill Rude – bloom where you’re planted (Seattle)

More ice

Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, General Aureliano Buendia was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.

– One Hundred Years of Solitude

Ice thread, previous posts, enter here.

Latest: Charles Kitchings of Ambach & Rice adds the essential Francis Alys and Francis Alys again.

Thanks, Charlie!

Mary Mattingly to Ford Gilbreath: Walking on water & breathing under it

Mary Mattingly, from her series, Nomadographies, just closed at Robert Mann Gallery.

A lot of Mattingly’s images look like photo shoots for a fashion magazine, which is not the insult it used to be. Art worms its way into contexts that were once excluded, partly because they were once excluded. Plus, within the glamorously provocative, Mattingly has that extra element, a subtle and toned-down version of Matthew Barney. She goes for the myth but leaves pomp and circumstance to others.

A lot of Mattingly’s images look like photo shoots for a fashion magazine, which is not the insult it used to be. Art worms its way into contexts that were once excluded, partly because they were once excluded. Plus, within the glamorously provocative, Mattingly has that extra element, a subtle and toned-down version of Matthew Barney. She goes for the myth but leaves pomp and circumstance to others.

(Mattingly is a key contributor to the Waterpod Project, which opens Saturday in New York City. (More info from Artforum and the New York Times.)

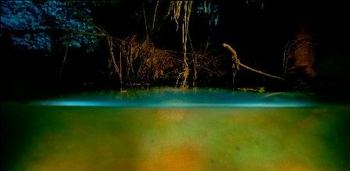

Ford Gilbreath has no relationship to the world of runway glamor. In spite of the pellucid clarity of his photographs, he’s happy to work in the mud and is best known for hand-painted gelatin silver prints shot on the Duwamish in Seattle, a river long abused by heavy industry. It has the distinction of having one of the lowest oxygen counts in the country.

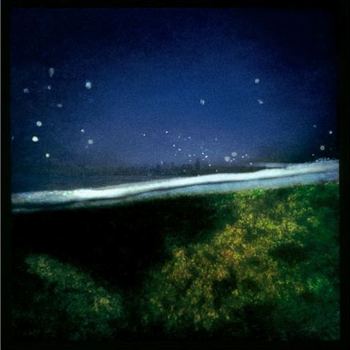

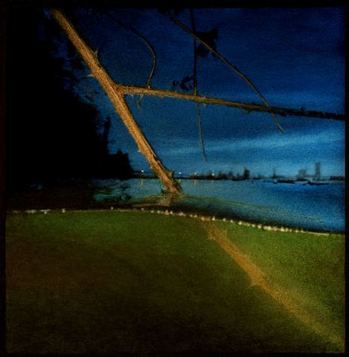

Gilbreath slogged through the river’s heavy-metal murk in chest-high waders, pushing his camera in front of him in a half-submerged aquarium. With flashes attached above and below the waterline to his Hasselblad camera, he produced a simultaneous look at two worlds: air and water divided by a fluid seam or horizon line. He added density to the stark, flattened effect achieved by the camera by painting the prints in layers with transparent oils.

Gilbreath slogged through the river’s heavy-metal murk in chest-high waders, pushing his camera in front of him in a half-submerged aquarium. With flashes attached above and below the waterline to his Hasselblad camera, he produced a simultaneous look at two worlds: air and water divided by a fluid seam or horizon line. He added density to the stark, flattened effect achieved by the camera by painting the prints in layers with transparent oils.

In his stagnant shallows, scum shines and greenish-brown depths

In his stagnant shallows, scum shines and greenish-brown depths

glow. He gives the drooping clumps of dead grass that hang over unnameable, watery masses scale and force beyond their size and importance. They are monuments in ruins, as graceful in their dying fall as the ruins of Greece and Rome.

Gilbreath on the moon here. His stereoscope images in the woods (here) are the only ones I’ve seen that don’t immediately ring the William Kentridge bell.

Gilbreath on the moon here. His stereoscope images in the woods (here) are the only ones I’ve seen that don’t immediately ring the William Kentridge bell.

Dave Horsey responds

Batting the verbal ball back and forth is one of my favorite things! Like Woody Allen, I don’t want to play tennis with the ocean.

Below, the best political cartoonist in the country responds to my post titled, Dave Horsey derides his former (fired) PI colleagues, here. (Well played, Dave. Match set. Your favor.)