Uncategorized

Kiki Smith – here in this life, this skin

To her friend Robin Winters, Kiki Smith said:

I don’t think my work is particularly about art. It’s really about me, being here in this life, in this skin. I’m cannibalizing my own experience, my surroundings.

Clearly this is true, but after looking at her work for 30 years, what do I know about her? Nothing personal. I know she appreciates animals both real and mythic, and that she thinks of fairy tales as a mother lode from which she extracts a mutable range of meanings.

In the 1970s, feminism was for her decisive. Through its lens she became an

In the 1970s, feminism was for her decisive. Through its lens she became an

artist. Whatever it is that the official art world

rejected, she embraced: small works on paper, coy/lurid/loose subject

matter, unreliable structures, the homemade and the handy: what she

could put together on her kitchen table.

Like a mole burrowing into a hole, she digs into the specific experience of women and animals in the world. (When a male makes an appearance, he is frequently a corpse.)

She’s interested in paws and feet; in heads, bellies, hands and claws;

She’s interested in paws and feet; in heads, bellies, hands and claws;

in tongues, eyes, blood and drool; in breasts and genitals, in skin

(both furry and bare); in ribs, breath and gesture: in lives lived under the

starry skies. Her idea of personal is treating herself as part of this image stream. When she appears in her work, it is as archetype

instead of individual.

Like a magician who can saw a woman in two without benefit of a box, she disappears in full view of the audience into her flagrantly candid depictions. In her youth she portrayed herself as a banshee girl, the one game enough to be wrestling on stage at the Kitchen in with David Wojnarowicz, or, as she put it, “beating each other up.” Before hitting 50, she rushed to embrace middle age, opening as it does the possibilities of the crone and harpy.

In his 2006 review of her mid-career retrospective at the Whitney, Holland Cotter found the essence of her gory yet exacting production:

In his 2006 review of her mid-career retrospective at the Whitney, Holland Cotter found the essence of her gory yet exacting production:

The tone is at once light and grievous; dreamlike dramas recur. There are miracles and martyrdoms, bursts of cruelty and hilarity. In a kind of boomerang karma, humans merge with animals, and animals have spiritual lives. Crystal tears pile up in corners; bones and worms are served up for meals.

Fanciful as it is, Ms. Smith’s art is also deeply, corporeally realistic. Step off the elevator on the Whitney’s third floor, and you’re in a wonderland version of a pathology lab. Empty glass jars carry the names of bodily fluids they are meant to hold: urine, sweat, saliva, mucus, milk, semen. A rib cage hangs on the wall near sets of internal organs. What looks like a flayed skin sits folded on a pedestal.

Each item has a freakish beauty. The ribs, cast in pale terracotta and held together by string, suggest chimes. The organs — male and female urogenital systems — are of a prettily patinated bronze. The folded skin looks plush and warm; it is made from panels of sheep’s wool stitched together with human hairs. (more)

Her approach to materials is inclusive, with no distinction between major and minor media, and yet, considering that she is best known as a sculptor, photography is a constant. Because it has always been there, at first incidentally and later with purpose, Elizabeth Brown’s exhibit at the Henry Gallery stands as a core inside the artist’s core: I Myself Have Seen It: Photography & Kiki Smith.

More is more: Many hundred postcard-size photos line the baseboards of the galleries. There are just enough sculptures to hold the show together, in glass, ceramic and bronze. Amid the photos are prints, some large-scale. Small black harpies perch above doors and on moldings, easy to miss but essential once seen, drawing the eye upward to engage the space, ceiling to floor.

More is more: Many hundred postcard-size photos line the baseboards of the galleries. There are just enough sculptures to hold the show together, in glass, ceramic and bronze. Amid the photos are prints, some large-scale. Small black harpies perch above doors and on moldings, easy to miss but essential once seen, drawing the eye upward to engage the space, ceiling to floor.

Smith likes to shoot at the edges of things, in her studio or at a foundry, in friends’ homes (never identifiable), in her yard. Her sculptures are just one element amid the smear of everything else: the worms on newspaper, the cat on its back, the hand of a sculpture, blue dusting its fingers.

In Brancusi’s photos of his work in his studio, he located the sculptures in a space they dominated. Smith uses photography to present her work as part of the wider world – an inflection instead of a narrative.

Within the fluidity of her range, however, she is the one who emerges, this woman who never lost a child’s awe and discomfort about the singular consciousness alive in her own body.

This is a show designed for repeat viewings, for skimming across the surface and for digging into particulars. I Myself Have Seen It runs through Aug. 15. It’s is a triumph for the Henry and a personal milestone for Brown, the Henry’s senior curator. Images do not by accident unfold with such inevitability, gallery to gallery.

Landscape as salvage

Scoli Acosta …Day Was To Fall As Night Was To Break, 2006

Gretchen Bennett, Williamsburg Bridge 2006

Gretchen Bennett, Williamsburg Bridge 2006

Matt Browning Portrait of the Outdoors, 2008

Matt Browning Portrait of the Outdoors, 2008

Aluminum cans, fiberglass, epoxy Robert Zverina, 1,000 flattened cans as a rising sun

Robert Zverina, 1,000 flattened cans as a rising sun

Claude Zervas Log and Beam, 2009

Claude Zervas Log and Beam, 2009

Vaughn Bell, Personal Landscapes (Don’t leave home without one)

Vaughn Bell, Personal Landscapes (Don’t leave home without one)

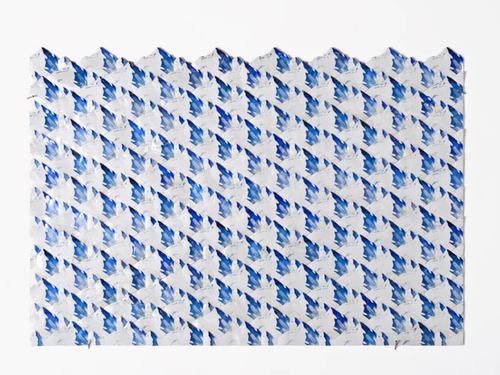

Genetics in clothing design

Quote of the day

Today’s changes won’t be noticed by readers.

(Story via AJ)

Reaction quote of the day, from Roger Ebert, same story:

RIP, schmucks.

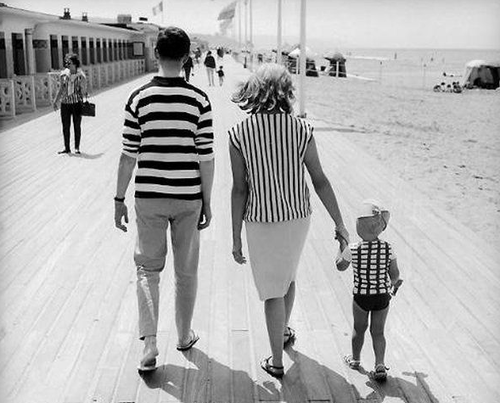

Up in the Air – the art version, then and now

Yves Klein Leap into the Void 1960 (Image via)

Have leaps into voids lost their exuberance?

Have leaps into voids lost their exuberance?

Has I-can-fly become I-can-die?

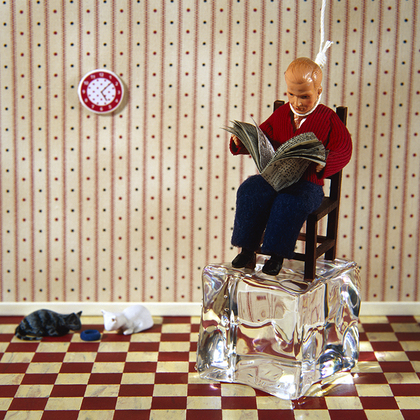

Grace Weston, Current Events (G. Gibson

Gallery)

Jonah Samson, On the Rock, 2008

Jonah Samson, On the Rock, 2008

Gratitude needs helium to stay afloat.

Gratitude needs helium to stay afloat.

Sean M Johnson

Thank You

2008

lawn-chair, balloons, string (via Howard House)

I am lonely, lonely./ I was born to be lonely./ I am best so!

I am lonely, lonely./ I was born to be lonely./ I am best so!

Joel Biel Tap Dancer, 2004

Mike Simi, Hummingbird Sneeze, 2009 (Play video here)

The past isn’t dead. It’s not even past. (William Faulkner

The past isn’t dead. It’s not even past. (William Faulkner

)

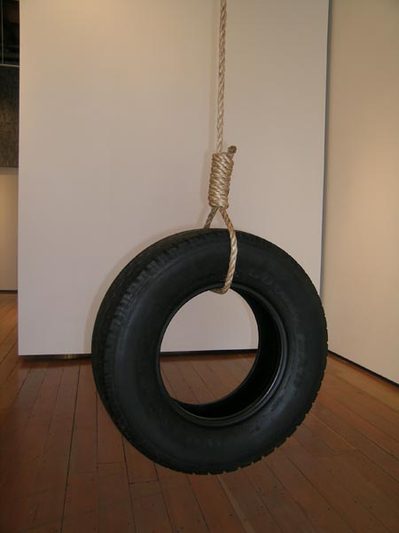

Jack Daws Strange Fruit, 2007

At least we can still throw our hats in the air.

At least we can still throw our hats in the air.

Barbara Noah Eureka, 2007

Robert Mirenzi – color in the bent world

Robert Mirenzi in earlier days:

In baking tins and

cardboard boxes painted to resemble baking tins, Robert Mirenzi’s loony assortment of

doll heads, doll hands and toy innards rise, as if full of yeast.

Some dolls are doubles of themselves, pink plastic casting plaster white

shadows. Some have lips sewn shut. Some are smeared with pale primary

paints. Tiny hands pop out of pull toys. Some heads are veiled, as if

wrapped to cool on a kitchen counter.

What distinguishes them from a century of similar surrealisms?

Their rigorous code, the structure that charges these oddball materials

with formalist rigor.

Mirenzi likes to start in the middle of a fairy tale and blunt all

suggestion of coherent narrative. The birds have eaten the crumbs

leading out of the forest. This point of paralysis inspires his art,

which is inventive, absurd and unforgiving. (via)

The toys are gone now. What’s left is what was there from the beginning, an industrial approach to aesthetic rigor inspired by the process artists of the 1970s. What he brings to their base is a comic air of insufficiency, a refusal to take up more space than he absolutely needs, an inclination to subtract rather than to add. Now that the dolls, frog’s legs and other broken toys are not there, it’s easy to see how unnecessary they were. For Mirenzi, the plainer, the better.

Nearly all of his current sculptures are small, from palm-size to arm’s length. Some sport some

kind of old metal frame or industrial pipe serving as frame.

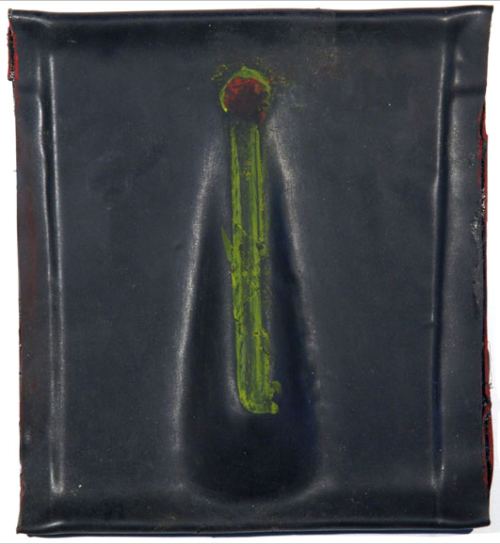

Untitled mixed media construction, 2009

6 x 7 x 1¼

inches

Whatever polish he brings to bear never obscures the down-and-out nature

Whatever polish he brings to bear never obscures the down-and-out nature

of his enterprise: funk on the cheap, industrial process sculpture

produced in the shadow of dying industries.

Color, usually an exhausted primary, is used sparingly.

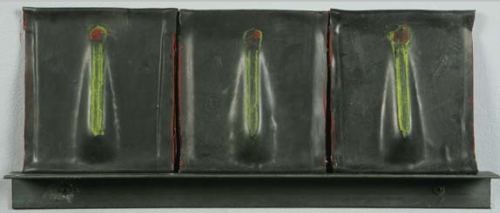

Untitled mixed media construction, 2009

15 x 45½ x 7¼ inches

Detail:

Detail:

He is a poet of comic insufficiency – toys gone bad,

He is a poet of comic insufficiency – toys gone bad,

hobbies ridden off the deep end and work a delusion.

As a theme, insufficiency has inspired its share of art, but not often

visual art. Writers have claimed it (Dostoevski, Kafka, Samuel Beckett,

Richard Wright, Donald Barthelme) and actors have embodied it (Buster

Keaton, Peter Lorre, Al Pacino, Lily Tomlin) but even the most humble of

physical materials acquires authority when structurally organized into

an artwork.

Artists seeking to glorify the shabby, from Kurt Schwitters and Louise

Bourgeois to Robert Rauschenberg, invariably transform

it into focused beauty, even elegance. And art made from coarse

materials that does not rise to elegance usually lacks a compositional

imperative and for that reason is hard to consider art at all.

Untitled mixed media construction, 2009

8 x 19¼ x 1¼

inches Here’s where Mirenzi shines. He can

Here’s where Mirenzi shines. He can

manipulate his unlikely combinations of crafted and found objects into

sculptures whose aesthetic power never undermines their projected sense

of powerlessness.They limp along out of anyone’s spotlight, even their own.

At Francine Seders through March 14.

Dina Martina – the crazy joy of failure

Because I live in Seattle and hadn’t seen Dina Martina, I tended to lie about it. I nodded at the tottering pile of appreciation always coming her way and added mine, falsely. Grady West, who created her, is easier to know. Soft-spoken, smart and thoughtful, his ability to listen distinguishes him. If I hadn’t already known that he’s an art collector, I could have talked to him for years without finding it out. He never asked if I’d seen his show. He doesn’t look like someone who’d be at his show, the show that I hadn’t seen. (Image left, the Stranger. Image right, Seattle Times.)

On Sunday, I became the person I pretended to be, shoe-horned into the camp locker room that passes for a theater at the Re-bar. It’s a holding tank for enemy insurgents, rimmed with pink tinsel. Said Dina, looking around with admiration: “Who doesn’t love mid-century modern?”

On Sunday, I became the person I pretended to be, shoe-horned into the camp locker room that passes for a theater at the Re-bar. It’s a holding tank for enemy insurgents, rimmed with pink tinsel. Said Dina, looking around with admiration: “Who doesn’t love mid-century modern?”

Space is limited. How much space is there for portly men impersonating glam women? Not much, and that’s where Dina begins, with nothing to prove and no apparent consciousness that such proof might be required after Divine, Leigh Bowery and Eddie Izzard; after the less-portly lovely ladies in Paris is Burning, from Pepper LeBeija and Dorian Corey to Anji Xtravaganza and Willi Ninja; after the adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert.

Honey, we’ve seen it. And yet Dina Martina shines in her Goodwill high heels. Admittedly, the greatness she seeks is out of her reach. She’s more like the principal of a nursing home donning drag for the annual fundraiser. She wants to cover the world in radiance but has none to offer. She’s queen for a day on a broken TV. She’s a fish being clubbed on a pier that imagines it’s swimming free.

What is drag but over-sized desires? Although modest, Dina’s are unattainable.

Mother of an enraged teen, she wants more children. “I have child adopting hips.” She’d like to lose weight. (Her new diet, only-eat-while-driving, is working, she said, her search-light smile faltering as she looks down at her blubbery self.) Almost instantly, her demented optimism engages anew in her search for a one-true-love.

At the Re-bar, she found it. A request for hands revealed few first-timers. Dina’s been holding court at the Re-bar since 1993. In Seattle, she’s a lot like a fundamentalist church. Believers would crawl through glass to get to her. (To a Sunday afternoon crowd, she said, “Thanks for choosing me over the Lord.”)

Some jokes are chestnuts. Most are new. The show constantly renews itself without breaking new ground, except in its videos. Dina grows older, still snapping her fingers to the beat and looking for gold in dumpsters. But the videos that began as scene changers have evolved into real scenes. Dina pasted her painted fish face over Rhett Butler’s. That’s her ogling Scarlett O’Hara as the Southern beauty climbs the stairs. Dina is the new kid on the block visiting The Brady Bunch. To its lobotomized cheer she brings crazed relish. She’s Shirley Temple dancing with Bill Bojangles as American racism squirms in its seat.

The melancholy undertow rarely breaks the surface of her gay patter. For that act of bravery, for the perfect timing of her shrill songs and brazen dances, the audience continues to love her, and not just in Seattle. Dina has taken her bad act on the road, achieving success across the country, in Canada and Europe.

March 20 and 27, she’s at the Re-bar. Have a drink with her during the show (“As they teach you in AA, you can’t change anything, so why bother?”) and salute what Hunter S. Thompson called the broken chromosomes of the American dream.

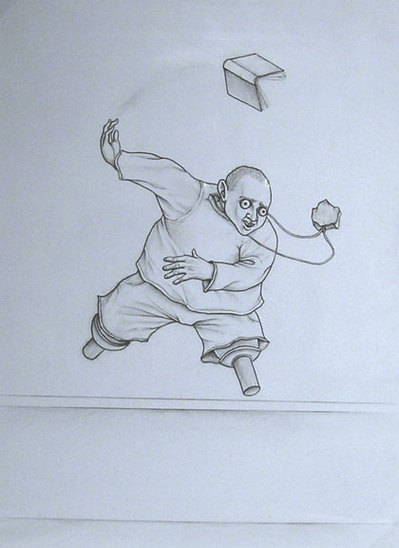

Michael Schall – the closer

Plenty of artists tell stories. Michael Schall‘s interest in a narrative quickens once it’s over. His drawings could be closers at a movie, coming up as final credits roll.

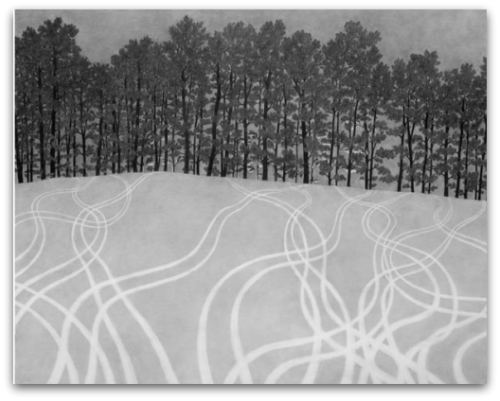

Snow Tracks

graphite on paper, 22 x 30 inches, 2009

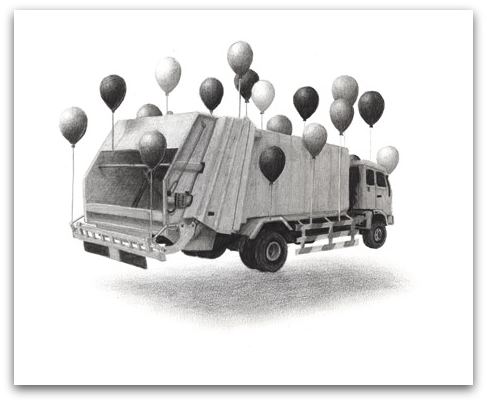

His drawings are not a final scene but what comes after, either as summary (Snow Tracks) or coda (Untitled below, 8 x 11 inches, graphite on paper 2009). Even if an ending proves grim, lead balloons can still lift a dump truck into the air – heavy things joining to defy gravity.

His drawings are not a final scene but what comes after, either as summary (Snow Tracks) or coda (Untitled below, 8 x 11 inches, graphite on paper 2009). Even if an ending proves grim, lead balloons can still lift a dump truck into the air – heavy things joining to defy gravity.

At Platform Gallery through March 27.

At Platform Gallery through March 27.

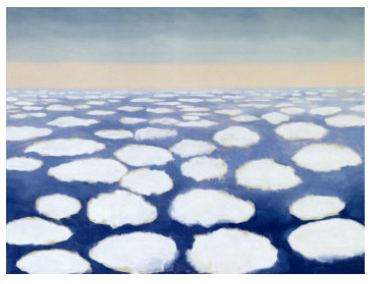

Georgia O’Keeffe’s clouds on the ground

Georgia O’Keeffe, Sky Above Clouds Chris Boyle, Spotted Lake, Canada, via Slow Muse

Chris Boyle, Spotted Lake, Canada, via Slow Muse