Robyn O’Neil, Occurrence, 2009 Graphite on paper 6.5 x 10 inches

John Grade, Seep of Winter, 2008

John Grade, Seep of Winter, 2008

Regina Hackett takes her Art to Go

Narratives encased in convention become fluid in The Old, Weird America: Folk Themes in Contemporary Art, inviting the audience to appreciate what Laura Lark called in her excellent review the “complexity of the iconic.”

Organized by Toby Kamps, senior curator

at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, the exhibit opened there

in May, 2008, and debuted at the Frye Museum on Saturday. It features 18 young to mid-career artists interested in the roots of an American experience that extends from the Pilgrims to the Space Race.

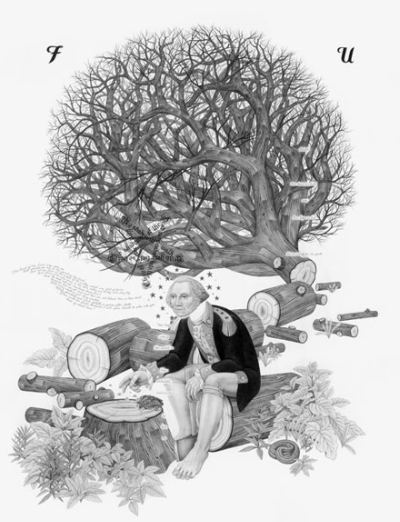

Eric Beltz, Fuck You Tree, (detail), 2007, graphite on board, 40 x 30 inches

Beltz gave the father of our country lovely feet. If he could stand, they could carry him out of this scene of morbid self-reflection. Instead, he sits on a log from his cherry tree with stars from the original 13 colonies ringing his face like mosquitoes, and his head detached from his body as if ready to be reproduced on dollar bills. The tree itself flourishes behind him as a rootless cosmopolitan, an entangling alliance.

Beltz gave the father of our country lovely feet. If he could stand, they could carry him out of this scene of morbid self-reflection. Instead, he sits on a log from his cherry tree with stars from the original 13 colonies ringing his face like mosquitoes, and his head detached from his body as if ready to be reproduced on dollar bills. The tree itself flourishes behind him as a rootless cosmopolitan, an entangling alliance.

The title of the show comes from the peerless Greil Marcus, who used it for his essay on Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes, in which Dylan paid homage to American blues and country folk.

Barnaby Furnas’ paintings are a giant step up from Ralph Steadman’s illustrations, which could be a source. Where Steadman relies on endlessly repeated flat splatter, Furnas opens the splatter with electric Kool-Aid colors, scale shifts and the narrative detachment of video games.

When James Baldwin was asked in the late 1950s if there were a candidate he could support for President, he answered, “Yes. John Brown”. The guns firing at Brown’s feet are candles and also flowers reminiscent of Anslem Kiefer’s.

Furnas, John Brown, 2005, Urethane/dye on linen, 72 x 60 inches.

[Read more…] about Godforsaken curios – The Old, Weird America

Seattle is the last stop for The Old, Weird America: Folk Themes in American Art, and Seattle is lucky to get it. As

art museums hunker down with long runs for exhibits featuring objects from their

collections, fewer shows travel. If the recession is over,

nobody told the art world.

The Old, Weird America would be welcome at any time. Organized by Toby Kamps, senior curator at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, the exhibit opened in Houston in May, 2008, and debuted at the Frye Art Museum on Saturday, just in time for Thanksgiving.

A review will follow but given the season, I’d like to consider separately Sam Durant‘s Pilgrims and Indians, Planting and Reaping, Learning and Teaching. Its revolving-stage, dual dioramas invite the audience to contemplate who is weirder: those who insist on a fictionalized version of American history or those who dispute it.

Durant purchased the dioramas from the defunct Plymouth National Wax Museum in Massachusetts. Initially, the museum displayed the accurate version of Thanksgiving’s origins: After Pequot Indian Pecksuot insulted Captain Myles Standish, Standish flew into a rage and killed him. Fearing retribution from Pecksuot’s tribe, Standish organized a raiding party and wiped out the Indians camped nearby. Afterward, settlers celebrated their win by declaring a national day of thanksgiving.

Durant purchased the dioramas from the defunct Plymouth National Wax Museum in Massachusetts. Initially, the museum displayed the accurate version of Thanksgiving’s origins: After Pequot Indian Pecksuot insulted Captain Myles Standish, Standish flew into a rage and killed him. Fearing retribution from Pecksuot’s tribe, Standish organized a raiding party and wiped out the Indians camped nearby. Afterward, settlers celebrated their win by declaring a national day of thanksgiving.

Over the years, the story transformed into its opposite: Pilgrims breaking not bones but bread with the land’s original occupants.

The factual diorama was removed after visitor complaints in the 1970s, leaving the story we know so well.

Reviewing the show for the Boston Globe, its art critic Sebastian Smee trotted out the usual insults for anyone questioning a master narrative from America the beautiful. Smee bemoaned the inclusion of:

familiar forms of patronizing “identity art” – art that addresses, in

the most dutiful, box-ticking ways, the familiar tropes of exclusion

and wrongdoing.

(Two familiars in one sentence? Maybe the Globe no longer deserves its reputation for great editors. I also note with dismay Smee’s lead, which for no good reason is in the passive voice. Had he wanted to leave a snail’s trail of inertia across his copy, passive would serve him. If not, not. )

Back to Smee:

I’m thinking, for instance, of Sam Durant’s two life-size dioramas that

suggest alternative interpretations of the first Thanksgiving. The

dioramas are set up on a circular platform, divided in half, that

slowly revolves. One side shows a Native American teaching a pilgrim

how to grow corn (with the help of a buried herring); the other shows

Captain Myles Standish beating to death the Pequot Indian Pecksuot,

which, the catalog tells us, led to a raid on the Pequots and

subsequent celebration.

Durant purchased both displays from the defunct Plymouth National Wax

Museum in Massachusetts. But to what end? The work he has made from

them is as didactic and kitsch as the originals, and it isn’t saved

from being so by the artist’s ironic know-ingness.

American exceptionalism means Americans never have to say they’re sorry.

Smee fell into the trap of reviewing the subject matter, not the art. I don’t mean to imply the trap is easy to avoid. Personally, I’m relieved to see accuracy creeping into American history by way of art or any other way, if only because too many American myths are found there and fuel attitudes that impede progressive change.

In reacting to Durant, I have to consider whether I am Smee’s twin, responding to what art says rather than what it is. And yet I think it is what it needs to be, an appropriation of frozen moments he sets in motion, fact and fantasy as each other’s form and each other’s shadow.

Flash mobs continue, via

Walking into a warehouse in Portland in 2003, I saw 10 old refrigerators lined up against a wall in an assortment of once tony shades: avocado, orange, dark brown. I opened one and saw a video of a wolf chasing what it hoped would be dinner. Each refrigerator contained a similar chase, but only in one did the wolf score. The title of the piece, Hunting Requires Optimism, struck me as the perfect metaphor for making art.

Vanessa Renwick, creator of Hunting Requires Optimism, is good with titles. (She calls her Web site the Oregon Department of Kick Ass.)

October 7 -9, she hosts a survey of Portland short films at the Northwest Film Forum, titled, A Natural Selection. Missing it is a bad idea.

Still from Melody Owen’s Kayavak

Rewick describes her survey as

Rewick describes her survey as

…some hopping films from Portland’s finest artists. Lions! Bicycles! Melting Polar opposites! Rabbits! Record Stores! Beluga Whales! Tears! Mind bending! and MORE!

They include:

That’s Fine, You’re Doing Perfectly by Karl Lind

Performance by Robin Moore

Lion Roars by Melody Owen

Moonbabies, part 1 of You Were a Perfect Gentleman and part 2 New World by Zak Margolis

Pain Is Fear Leaving Your Body by Alicia McDaid

Storm Studies 1 by Liz Haley

Kayavak by Melody Owen

Portrait #3: House of Sound by Vanessa Renwick

A Vertiginous One by Zach Margolis

Psychic City by Judah Switzer

Straight out of Texas, Rainey Knudsen, founder and director of Glasstire, was the star of the first ever National Summit on Arts Journalism, held in L.A. on Friday. More on Glasstire to follow, but first, a few words about Douglas McLennan, who conceived it and produced it with Sasha Anawalt.

McLennan is best known as founder and editor of ArtsJournal. If you’re reading this, you’re on an AJ site. ArtsJournal is an aggregate of arts news in English around the world, with the additional of a streaming rail of posts from AJ arts bloggers, including me.

More alliances: I live-blogged the summit, here, at Doug’s request. Throw in my friendship with him and clearly I have a dog in this, which influences but does not account for my belief that the summit went well.

Given the free fall of traditional arts journalism, this summit is the first to consider options for replacing it.

Tyler Green (AJ blogger) and Paddy Johnson (nonAJ blogger) were disappointed in advance. Both objected to the idea that a nonprofit can be a business. They say opening the competition to nonprofits was changing the rules.

Although I hesitate to dispute a business question with two people whose entrepreneurial savvy overwhelms my own, I side with the summit on this one. It never said nonprofits couldn’t apply or weren’t businesses.

Nor did it change the rules by “adding” five project models.

After an open call for entries, jurors selected five models to present at the conference. From these, NAJP members voted to select three top entries, all of whom will get cash awards, starting at $9,000. (Winners not yet announced.)

In addition, the Summit asked representatives from five businesses working in support of arts and/or arts journalism to present. They were not part of the contest, were not chosen by jurors and are not eligible for awards. In saying the summit added five projects after the fact, Johnson and Green are factually wrong.

Johnson also wrote that she didn’t watch the summit, which was live-streamed around the world and is still available. Disclosure is good, but why didn’t she watch, especially as she intended to write about it? Even though she was traveling when it took place, she could have caught it later.

On the other hand, I can’t help but admire the vigorous way she attacked McLennan’s baby. He was on the Warhol grants panel this year and successfully argued for her to get one. If speaking her version of truth to power means biting the hand that feeds her, she chomps down.

Back to Glasstire, which Johnson praised as a good model. (Note to Johnson: it’s a nonprofit.) It covers Texas, which is a way of covering the world, as a lot of art flows through the Lone Star State. In nearly a decade of existence online, Glasstire has attracted terrific writers and given them a platform to be regional without being narrow.

I also like that it’s not a design wonder. It serves those who want to think about art, not just click through razzle-dazzle. Its existence is a fundamental challenge to those who maintain that New York and L.A. are where the U.S. art action is, and artists/critics living elsewhere are delusional.

Because time is a way of keeping events from happening all at once, it tends to bury the past. Anyone who wants to see it again has to dig. In Seattle, artREsource offers that opportunity. It’s a regional resale gallery, providing a secondary market for collectors and a chance for the larger audience to see what is no longer current, such as Gene Gentry McMahon’s untitled mural from

1983-84, oil on canvas

24 x 168.75 inches, via

Detail:

Detail:

McMahon paints in a comedy-of-manners vein. Back before anyone thought William Hogarth had anywhere to go other than the slag heap of history, she was Hogarth in stilettos, painting

women on the make flirting with underworld thugs.

After that, she developed the most famous case of artist block in the region, down but not out, fighting through two bouts of breast cancer (hers and her daughter’s), holding down a day job as party props creator and struggling to keep her studio practice alive.

Last year, she bounced back with a terrific show at the Grover/Thurston Gallery.

Her self-portrait in that exhibit, Pinkie, 20 x 22 inches, 2008, suggests a new level of self-sufficiency. This figure needs a man like fish needs a bicycle.

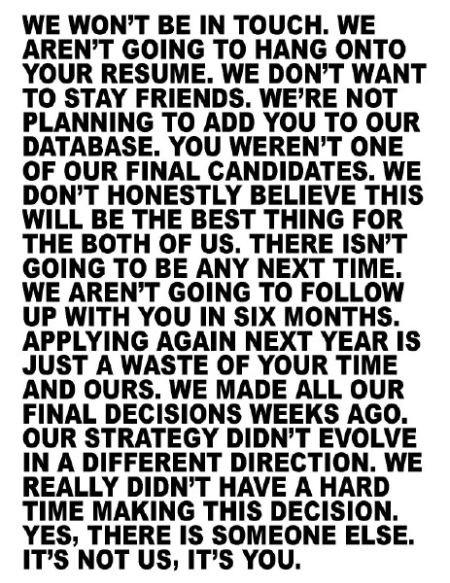

Anthony Discenza, the consolation of art:

an ArtsJournal blog