You think it’s over. It’s not over. (via)

Regina Hackett takes her Art to Go

You think it’s over. It’s not over. (via)

At 12.5 square feet, The Telephone Room in Tacoma is not the smallest gallery in the world but must be in the tiny top ten.

From its Web site:

It is located in a Dutch Colonial home in Tacoma and since 1930, its sole purpose has been to house a black rotary dial telephone. Until now…The Telephone Room is small, but its mission is big: to house artist-driven exhibits and programming. Big ideas in an intimate space.

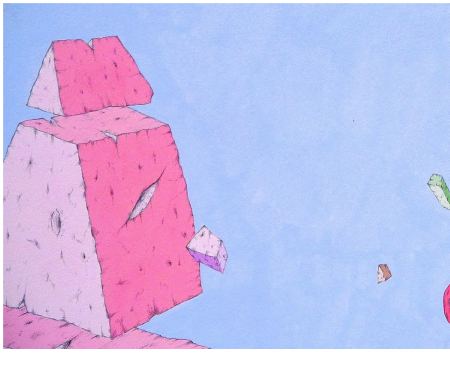

Opening tomorrow night are Blake Haygood‘s new drawings under the collective title of Is You Is, in gouache and graphite on ragboard.

Haygood began as a printmaker and still paints in a modified printmaking style, incising form into wood panels and painting in layers through a process of erasure, laying on and partially wiping out. When he began painting earlier in the decade, acrylics in a mineral varnish woke up his

Haygood began as a printmaker and still paints in a modified printmaking style, incising form into wood panels and painting in layers through a process of erasure, laying on and partially wiping out. When he began painting earlier in the decade, acrylics in a mineral varnish woke up his

weightless world.

Born in Athens, Ga., in 1966, he grew up in a smaller, more rural town nearby, spending a lot of time at his grandfather’s farm bordered by woods.

Untended, the farm had slid into disrepair. Beyond a barn with a caved-in roof and machinery rotting in the field was the woods, also strewn with broken machines.

A walk in the countryside meant a scramble over dumped refrigerators, cars and parts of cars, washing machines, buzz saws, bikes and bed posts.

Wild grasses, mosses and tree saplings used the machinery as nurse logs, shooting up inside it and growing large enough to shoulder it aside or bury it.

Haygood’s new work has moved beyond the semi-pastoral decay of the old South to explore more remote cosmologies. Inside them, densities of cut stone or wood linger on their blunt bases before pushing off into the air. His forms may be eroded, but his soft hues are always brand new. He is a master of the potent blank. He takes his cues from traditional Chinese landscape artists who created air, water and mountains largely by leaving them empty. Haygood’s forms are lovely, but it’s the colored air around them makes them matter.

Is You Is is half a line. Musically, it ends in a love song. Although Haygood uses the reference to mark a career turning point, no longer part-time painter and part-time art dealer but painter full-time, his paintings make the song their own. What is lost, ruined or left behind is desirable again in the redeeming space he makes for it.

Update: Better image via

Biel opens at Nettie Horn on Nov. 20.

Portland writer K. B. Dixon‘s new novel, A Painter’s Life,

is unwieldy but precise. It reads as if it’s a journal kept by the (fictional) painter Christopher Freeze, but unlike a journal, this sack

of asides, hopes, press clippings, musings on friendships, work, other

artists, critics, dealers, paint and the point of paint adds up to a

life.

What’s more, it’s a life in Portland. We in Seattle

imagine Portland artists constantly having dinner. Even a resolute

outsider such as Freeze would have plenty of friends in Portland, more

than his narrative can keep track of. His friendships are the cushion

he leans on to keep his solitary occupation in motion.

When

Seattle artists look up from their work and realize they haven’t talked

to anybody in a month, Portland’s collective comfort

zone looks good.

Below, a few quotes from the book for its flavor, with images of paintings from a few of Portland’s nonfictional finest.

David

Andres was saying if he could just get the right people to object to

something of his, to insist that it be removed from wherever it had

been placed, it would be the making of him. It would mean a reputation,

which is money in the bank. It would mean a better bottle of wine with

dinner, a car with more horsepower, a house with more square feet, a

girlfriend with fewer cats.

James Lavadour, Blue Back

I

like my pictures to look crowded – sort of stuffed into the fame. The

canvas should be full like your plate when you sit down to dinner –

suggestive of emotional and/or metaphysical abundance.

Judy Cooke, Ice Melt

I

don’t want to be part of the perpetual revolution, the chasing after

novelty. The freedom to go where you want is one thing, but the

obligation to move on, move on – that is the demand made by a

policeman. You are never saying anything; you are trying to say it. You

never get to finish or to amplify a thought.

Anna Fidler, Correspondences

I hate watching people look at my pictures. I never like anything about the way they do it.

Adam Sorensen, Squall

My

father claimed he could smell electricity, and my mother was always

telling us how many hours it had been (plus or minus a quarter) since

this or that person had bathed or showered. I myself am similarly

sensitive. The stench of the studio is one of the things I like best

about being a painter.

Storm Tharp, Approaching Thunderhead

I don’t think of my pictures as small – I think of them as efficient.

Previous post here.

From the National Summit on Arts Journalism:

First Prize of $7,500 goes to Glasstire (www.glasstire.com) of Texas. Second Prize of

$5,000 goes to FLYP Media (http://www.flypmedia.com/)

of New York City. Third Prize of $2,500 goes to San Francisco Classical

Voice (www.sfcv.org) . Additionally, all

three projects, along with finalists Departures (a project of KCET in

Los Angeles http://kcet.org/explore-ca/departures/ )

and Flavorpill (www.flavorpill.com

), previously were awarded $2,000 each for being chosen finalists for the

National Arts Journalism Summit.

The purpose of the summit was not a search for content. Content is not what’s broken. It was a nationwide call for new delivery systems for arts content, be it through criticism, photo essays, videos, forums and/or arts-driven social networking sites. Interesting, then, that NAJP voters chose to award first place to the site with the best content.

Makes sense. NAJP members are mostly critics. Critics want a place to write and the opportunity to be paid for their work. With wit and energy, Glasstire provides both, although writers are largely freelance: few living wage jobs available.

Coming in second, FLYP Media is a design marvel, but so far tends to be weak on content. If the editors undertake to improve the writing (and that means also the thinking) of its offerings, it will be able to offer genuine employment to writers, who so far play a secondary role. A brainy FLYP would be huge.

If the Seattle Art Museum is waiting for a thumbs-up on its Michelangelo debacle, it’s going to have to write one for itself. Walt Whitman did so under a pseudonym for Leaves of Grass, and his reputation remains unsullied.

The closest thing to favorable are Victoria Ellison’s three paragraphs tacked on to the end of her Calder review.

The decision to turn Michelangelo into a Calder postscript pushes in

the opposite direction of her generous comments. (Whose work got the

illustration? Calder’s.)

(My Michelangelo review here. My Calder here.)

In his fine Calder review, Stephen Cummings reduced his reaction to Michelangelo to the following:

It may go without saying that SAM has a bit of a (deserved) reputation for mounting second rate shows. (Michelangelo certainly qualifies.)

If

SAM has this reputation, it is unearned. At the region’s flagship

museum I’ve never seen an exhibit as overblown and underfed. It’s the

kind of thing John Buchanan used to surround with superlatives when he was fund-raiser-in-chief director of the Portland Art Museum. He has since taken his brass-band personal style to the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, causing Kenneth Baker great dismay.

Back to Walt Whitman:

The 1855 publication of Leaves of Grass

was heralded by anonymous reviews printed in New York papers, which

were clearly written by Whitman himself. They accurately described the

break-through nature of his “transcendent and new” work. “An American

bard at last!” trumpeted one self-review. (more)

Anyone caught doing that today would surely share the fate of James Frey. He took a beating for his memoir, A Million Little Pieces, discovered after publication to be partly fictionalized. In response to his critics, Frey commissioned a painting by Ed Ruscha. (Story here):

No story ever happens the way we tell it, but the moral is always correct.

Donald Barthelme, from The Dead Father

Jessica Reed, the person who found Jack Daws‘ counterfeit penny, is an artist. Here’s a cake she made in February in honor of Abe Lincoln’s birthday, starring his portrait on (what else?) a penny.

(Previous post here.)

(Previous post here.)

The chances of anyone noticing the penny Daws cast in gold and slipped into circulation at LAX more than two years ago are slim. On the side of discovery, it’s slightly smaller than the ordinary one, because gold is heavier. If Daws’ penny were the usual size, its weight would have given it away. As it is, it’s three grams to a penny’s two.

This weekend, Reed send Daws an email explaining how she found it.

“This is a story about finding a penny, but it begins with a dime. As for how it all ends, of that I have no idea…

“This is a story about finding a penny, but it begins with a dime. As for how it all ends, of that I have no idea…

On Monday of last week (the 26th), I was counting out the 44 cents I needed to complete a purchase when I spotted an unfamiliar coin in the lot. Looking closer, I realized that it was a U.S. dime, minted in 1924, but unlike any dime I’d ever seen.

Once home, I did a Google search and identified the dime as a 1924 Mercury Head; not very valuable, but beautiful none-the-less.

Researching it reminded me that I had another unusual coin in my possession–a golden penny. I’d had it for a few months ( at least) having noticed it when I was paying for groceries at the neighborhood C-Town.

Here’s a review by Jen Graves that makes a fetish out of burying the lead:

My mother and father didn’t work out; my mother

remarried during a blizzard at the Old First Church in Bennington,

Vermont, where Robert Frost is buried. This place, which around this

time of year will smack you silly with beauty, is less than an hour

from our house in small-town upstate New York, and on the way is a

museum we’d often stop at, the Bennington Museum. That museum has just

one claim to fame: its unparalleled collection of paintings by Grandma

Moses. The headline of her obituary in 1961 in the New York Times read,

“Grandma Moses Is Dead at 101; Primitive Artist ‘Just Wore Out,'” and

the obituary contained the remarkable line “Grandma Moses did all of

her painting from remembrance of things past.”

The above paragraph is not a wandering path to a Grandma Moses review. The alleged subject has nothing to do with

her. And yet, there’s more:

Grandma Moses may be the

first recognized painter whose paintings I ever saw. Her story is like

my mother’s. She lived on a farm. She started painting at the age of 76

because she couldn’t stand the thought, as the Times put it, of being

idle. My mother does not paint, but now in her 60s, she is on her

second career, which is more strenuous than her first.

Still more:

Despite

all those visits to the museum, I do not recall any single painting by

Grandma Moses, but that’s not really how Grandma Moses paintings work.

You remember them in aggregate–their belief in warmth despite snow,

their belief in the delight of brightly colored sweaters, their belief

in the togetherness of tiny amiable sticklike people (she squeezed them

in last, working her compositions downward from the sky) who, as again

the Times pointed out (it really is quite an elegy for being so

offhandedly journalistic), “cast no shadows.” You remember them for

their belief, period. “You have no idea how much you can handle until

it happens,” my mother always says, promising the strength of the

American character whatever might come. Conviction is the core of

folklore, not style. Folk art is not just a matter of untrained marks,

but of untrained marks imbued with an unwavering but not entirely

plausible sense of their own worth against the odds.

Once the review

clears the hurtle of its preamble, it’s terrific. There are slender

metaphoric threads connecting the body of the text to the heavy weight of its

opening, but why must the text carry this burden? Lucy Lippard used to do

this in the 1970s. It went out of style, but it’s back. Graves, who appears to be still upset by the breakup of her parents’ marriage,

has saddled herself with its practice.

Reviewing the same show for Glasstire,

Laura Lark also took time to tell us about herself. Lark’s lead works

(unlike Graves’) because her confidences serve as welcome mat to the

subject she will in time get around to: The Old Weird America, now at the Frye Museum, its last stop.

A few years back a heavy package arrived at my door, addressed to my

then-husband. Inside was a bronze statue of a realistically rendered

cowboy riding a bucking bronco. Perfectly hideous. Think George H. W. Bush statue at Houston Intercontinental Airport. Who would send us such a thing?I used it as a centerpiece for dinner parties. It got a lot of laughs. After the joke wore thin, I used it as a doorstop.

We later discovered that the statue had been intended for a

wealthy and powerful member of the UT Longhorns alumni association who

had the same name as my ex-husband. The man sent a special courier to

pick it up and was none too pleased when I refused to re-package it.Months later, my husband came home with an issue of Time

magazine, opened to a picture of George W. in the Oval Office. In it,

Bush grinned and shook hands with folks in his good ol’ boy fashion.

Behind him, on a shelf, was either the statue — our statue — or a

replica by the same artist.No doubt Bush viewed the statue as a symbol of American

ruggedness and independence — something he desperately wants to be

identified with. I viewed that little slice of Americana as pure

kitsch.

The Old, Weird America, currently on view in the main

gallery at the Contemporary Art Museum Houston and organized by CAMH

senior curator Toby Kamps, tells a more nuanced story.

Even though Lark

sold me this time out, critics who think the audience needs to be

chatted up before it will tolerate the rigors of a review are mistaken.

Better to aim for the rarities of rigor and momentum, and let

the review carry itself.

Graves doesn’t agree, and why should she? She’s pitching in a different game. While my sort of critic wants to disappear into the art, she wants the art to disappear into her. A less biased way to say the same thing might be, she wants art to be metaphorically illuminated by her personal story. Her risks are grandiosity and self-absorption, but the nearly-impossible-to-achieve payoffs are essays that transcend their genre, in which a critic becomes an artist. I think she’s good enough to get there. Surely it’s brave to try. I’d rather lose a digit.

an ArtsJournal blog